Copyright 2006 by Eileen Welsome

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: June 2006

ISBN: 978-0-316-06958-8

The Little, Brown and Company name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Contents

ALSO BY EILEEN WELSOME

The Plutonium Files:

Americas Secret Medical Experiments in the Cold War

For Libby, Racheal, Courtney, and in memory of Jay

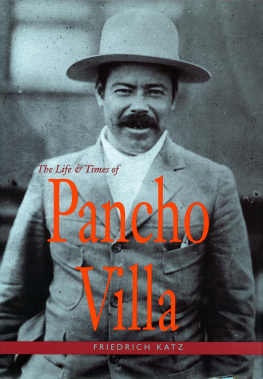

I can whip Carranza and his entire army, but it is asking a great deal to whip the United States also, but I suppose I can do that, too.

PANCHO VILLA, on the eve of the battle of Agua Prieta, October 31, 1915

WHEN THE SOLDIERS saw the yellow lights of the ranch house, they were seized with hunger.

Sometimes they lived for two or three days on a handful of parched corn, and the thought of well-cooked beef and hot green chiles stimulated their dormant hunger pangs. Still, they did not dare spur their tired mounts past the erect back of the colonel and continued to follow him down the hill.

The troops traveled mostly at night, wrapped in their serapes and sunk deep into their saddles, the clink of bridles and the occasional ping of a horseshoe the only sounds on the trail. By restricting their movements to darkness, the soldiers were able to evade the watchful eyes of their enemies, but the cold marches had sapped their strength. Once the sun rose and fell upon their faces, the men slipped into jittery, colorless dreams on the backs of their moving animals. The heat soon brought its own misery: the chafe of rotting clothes and the unbearable itch of unwashed bodies. They were tortured by lice, by mysterious rashes, by abscesses and pimples that covered their buttocks, their groins, their backs. Some were scarred by smallpox, others with poorly healed wounds. They had grown listless and numb, except for the buzz of anger deep in their brains. The ponies and mules suffered, too. White worms bored into their withers and their backs were covered with sores that oozed and spread each evening when the blankets were removed. The little animals did not cling to life and often died with a quick sigh, collapsing under their riders along the frigid mountain passes or in the alkali dust of the desert. While their bodies were still warm, they were butchered and their meat strapped onto the saddles.

Picking their way down the slope, the soldiers leaned back on their mounts to lessen the strain on the front legs of the ponies. Gray palomas whirred up in front of their faces and all around them were loose, treacherous rocks and the thorny pull of cactus and mesquite. With dusk came a penetrating cold, but it was early spring and a blue light still lingered in the sky. Mountains curled along the horizon, fields lay waiting for crops, and crows exploded from thickening branches of cottonwood trees, their ragged cries accentuating the stillness of the land.

Drawing near the ranch house, the soldiers could see a young woman, her soft, brown hair tucked up in a dust cap, moving back and forth in the window. They smelled animals dozing in their straw stalls, a tank of drip water, and food; something hot and bubbling on the stovebeans probably, seasoned with a few hunks of last winters pork, and cornbread or biscuits in the oven. Once again, hunger gripped them.

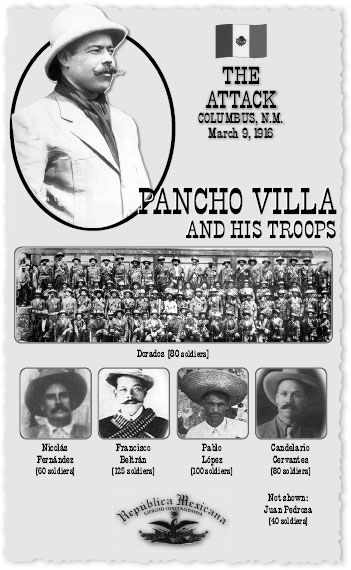

Colonel Nicols Fernndez dismounted from his horse and walked across the courtyard, passing a small adobe dwelling where the hired help lived, and headed for the main house. He was six feet tall and thin, with fine, almost delicate features and deep-set, gray eyes inherited from German ancestors who had settled in Mexico in the seventeenth century. He wore a khaki uniform, leather leggings that came up over the knees, and on the front of his battered hat was a bronze insignia the size of a silver dollar with the word Dorado inscribed in the middle. Though his clothing was dirty and his face hollow with fatigue, he was a commanding presence. He stamped the dust from his boots and knocked.

Maud Wright touched her hand to her cap and jerked open the door, staring fearlessly at the cloaked visitor. Beyond the colonel, in the courtyard, she counted a dozen soldiers, their dead eyes trained on her. More soldiers were pouring like dark water down the hill. She saw a rind of blue sky, a few faint stars, and no sign of her husband, Ed, or his young friend, Frank Hayden. The two men had left for the nearby town of Pearson earlier that afternoon to buy supplies and she expected them back momentarily. A small tingle of fear ran down her backbone, but she stepped forward and welcomed the officer.

Speaking in courteous, mellifluous tones, he introduced himself and asked her if she would be willing to sell him food.

Puedo comprar comida para mis soldados?

No tengo muchsimo. Pero se doy lo que puedo.

Maud had only enough food for herself, her husband, and the hired family, but said she would give him what she could. The colonel smiled tightly and swept past her into the warm kitchen. He glanced at her son, Johnnie, who was almost two, and already spoke a few Spanish and English words. When Fernndez had satisfied himself that no one else was present, he relaxed and grew more talkative. He said that he and his troops were Carrancistas and were hunting the bandit Pancho Villa.

Maud nodded noncommittally. Their small ranch was located in the state of Chihuahua, about a hundred miles south of the New Mexico border. She and Ed had been living in Mexico off and on since 1910, when the Mexican Revolution first began, and knew that their long-term survival depended on their ability to remain neutral and friendly to all sides. In 1913 they had been driven out of the country with more than a thousand other foreigners, but had returned the following year. They had rebuilt their modest herd of cattle and horses and moved back to the ranch in February 1916, just a few weeks earlier, thinking the worst was over.

It was easy to think that way. After years of civil war, the Mexican countryside was bleak and empty. Fields lay fallow and small shops and stores had been looted so often that the shelves were bare. There was no food, no medicine, no clothing. Curtains, carpets, and even the green cloth that covered pool tables had been ripped up and fashioned into clothing. When that was gone, the people had covered themselves with corn sheaves and string. Thousands were dying from tifustyphus. Starvation was claiming an even greater number of lives. It was the custom, remembered Martin Lyons, a mining engineer, to pick up little children and people sleeping in doorways and shake them to see if they were dead or alive and many times they were dead.

Bandits of all kinds roamed the countryside, robbing both foreigners and the native born. They extracted loans from mine owners and lumber-mill operators and kidnapped wealthy landowners and held them for ransom. Villas troops were invariably blamed for the depredations, yet the people in the villages and towns knew that the Constitutionalist troops commanded by Venustiano Carranza, the self-proclaimed

Next page