CONTENTS

The JB-1 Bat manned glider produced by Northrop in 1944 to test the flying qualities of a power bomb inspired by the German V-1 Doodlebugs. At first sight it resembles the Lippisch DM-1 shown on page 170, but the Bat has a conventional tail and swept wings unlike the DM-1s Delta configuration.

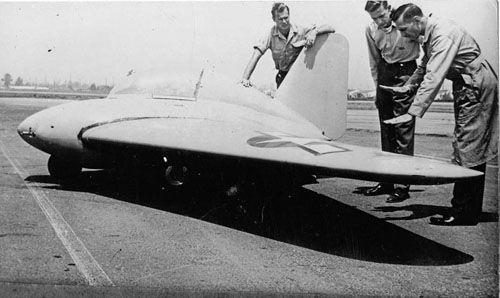

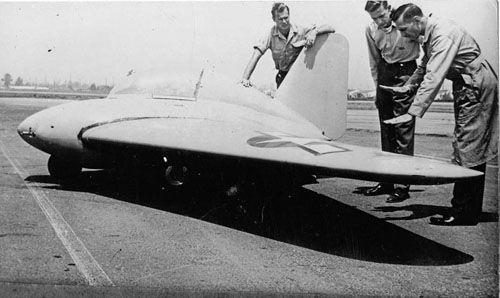

Typical of the scenes encountered by the advancing Allies in 1945, an abandoned airfield littered with a variety of German aircraft including a Messerschmitt Me 262A. (NARA)

Images have been obtained from a number of sources including the US National Archives & Records Administration (NARA), United States Air Force (USAF), Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust (RRHT), US Library of Congress (LoC), US Department of Defense (US DoD), Deutsches Zentrum fr Luft- und Raumfahrt Archive (DLR), National Aeronautics & Space Administration (Nasa), the San Diego Air & Space Museum (SDASM), Campbell McCutcheon (CMcC), Nimbus227, MisterBee1966 and Rottweiller. New photography is by the author (JC). Thanks also to Shaun Barrington of The History Press for his patience, and to my wife Ute for her support, proof reading and assistance with translations.

introduction

IN THE LATER STAGES of the Second World War the skies above Europe were filled with death and destruction on an unprecedented scale. Day and night the endless hordes of Allied bombers were pounding Germanys cities and war factories to dust. But as Hitlers thousand-year Reich faced its darkest hour, its Gtterdmerung , the twilight of the gods, the Fhrer unleashed an arsenal of deadly Wunderwaffe ; the wonder-weapons which he believed could turn back the tide in Germanys favour. These included not only the V-1 flying bombs and V-2 rockets, the Vergeltungwaffen (meaning reprisal or revenge weapons) intended to shock and awe the British into submission, but also a range of highly advanced jet- or even rocket-powered aircraft together with a plethora of guided missiles designed to strike at the enemys bombers. Such was the extent and sophistication of these weapons that in most cases they were ahead of any technology possessed by the Allies. If the German forces had managed to delay the Allied advance even by just six months or by a year the new weapons might have become available in sufficient numbers to change the outcome of the war.

Fortunately Hitlers war machine came to a grinding halt in the spring of 1945. With overwhelming Soviet forces pushing their way through the streets of Berlin and just a block or two from the Reich Chancellery, Adolf Hitler took his own life on 30 April 1945. General Alfred Jodl, Chief of Staff of German Armed Forces High Command, signed the documents of unconditional surrender on 7 May, signalling the surrender of all German forces to the Allies on the following day.

The conclusion of the war (in the European theatre at least, as the Pacific war still had several more months to run) brought to an end a conflict noted not only for its terrible toll in human suffering, but also for the massive technological strides made in the fields of aviation and armaments. This was particularly so in Hitlers Germany and the legacy of his scientists and engineers was a lexicon of new weaponry including jet-fighters, inter-continental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), guided missiles and smart bombs. Even before the end of hostilities the Allies had recognised that possession of this technology, not to mention the German scientists and engineers, held the key to power in the uneasy post-war peace. Inevitably there were other factors of course. In particular the Americans desperately needed to prepare themselves in case they encountered similar weapons that Germany might have shared with it Axis partners in Japan. Then there were the wider issues of retribution, compensation and commercial gain, not to mention the very genuine concern that Germany should not be able to rearm herself as she had done in the decades after the First World War.

A remarkably intact Messerschmitt Me 262A abandoned in a forest clearing beside the Autobahn. In the final stages of the war some motorways were used as makeshift airfields. (USAF)

It was against this background that the defeat of Germany in May 1945 signalled a frantic technological supermarket sweep undertaken by the Allies and a widespread plunder of the fallen nations resources. It was as if Germany was a sweet shop and the advanced aircraft and weaponry, the research and production facilities, the papers and documents, even the scientists, engineers and technicians, were the sweets to be stuffed into the victors pockets. To the Allies these were the rightful spoils of war and in the headlong rush to acquire them the needs of the defeated were cast aside. Time became the enemy. The Allies were in a race not only against looters looking for valuables in the various facilities, but also the wanton vandalism of the slave workers and prisoners who sought revenge against their former oppressors. And, of course, they were in a race against each another. Ostensibly America and Britain collaborated in their efforts, but as for the Russians, that was a different matter altogether. To further complicate the situation, alterations to the Allied Control Zones meant that some areas would change hands within weeks of the war ending.

In recent years much has been published and broadcast on the Americans efforts to bag the best of the Nazi technology, including Operation Lusty (a somewhat tortuous acronym derived from LUftwaffe Secret TechnologY) and Hal Watsons legendary Whizzers, a team of crack American pilots who scoured the ruined airfields of Germany to secure the latest jet aircraft, such as the Me 262, Arado 234 and the rocket-powered Me 163. The spotlight has also been turned on the German rocketry experts and scientists taken to the USA under Operation Paperclip and their part in launching the space race that put a man on the moon. These have tended to overshadow the less glamorous role played by the British.

During the war the British had been actively engaged in evaluating captured German aircraft, most notably at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough, and the round-up of enemy aircraft continued after Germanys capitulation. The British sent technical intelligence teams to work in cooperation with the Americans under the control of the Combined Intelligence Objectives Subcommittee (CIOS). But there was one post-war British mission to Germany that stood apart from the others, and it was the one I stumbled across by chance forty years after the war had ended.

The Fedden Mission to Germany Final Report proclaimed the title on the faded tan-coloured cover of the document among a box of papers at a local auction of furniture and general items. Many of the lots in the auction came from house clearances of estates following the death of their owners and the report was with a number of aeronautical reports, papers and photographs relating to the Bristol Aircraft Company. This was located at Filton, just to the north of Bristol and approximately 15 miles from the auctioneers. There was much about this document that attested to its interest and its significance. The word Secret caught my attention initially, and then there was the striking logo adorning its cover. Clearly someone had taken the trouble to design and draft a special logo, an act which seemed whimsical, almost inappropriate, given the official nature and content of the report. (I later discovered that this had been devised by Sir Roy Fedden himself.) This simple graphic device encapsulated the story contained within. Here was the swastika, the instantly recognisable emblem of the hated Nazi regime, with the German eagle pierced through its heart by a spear-like flagstaff bearing a Union Jack, and around the edge were token stars and stripes to represent the USA. Even now the message is blunt, almost shocking. It symbolises the total and absolute defeat of Germany at the hands of the Allies, or, more precisely, the British and Americans, as the hammer and sickle of the Soviet Union are conspicuous by their absence.