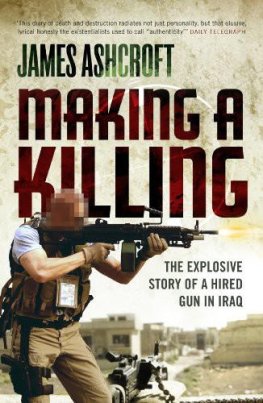

James Ashcroft

with Clifford Thurlow

MAKING A KILLING

THE EXPLOSIVE STORY OF A HIRED GUN IN IRAQ

IN MEMORIAM

Philip

Jason

Mohanned

Hayder

Riyadh

Khaled

How dull it is to pause, to make an end,

To rust unburnishd, not to shine in use!

Alfred, Lord Tennyson,

UlyssesThe rain fell alike upon the just and upon the unjust, and for nothing was there a why and a wherefore.

W. Somerset Maugham,

Of Human BondageNever, never, never believe any war will be smooth and easy, or that anyone who embarks on the strange voyage can measure the tides and hurricanes he will encounter. The statesman who yields to war fever must realise that once the signal is given, he is no longer the master of policy but the slave of unforeseeable and uncontrollable events.

Sir Winston Churchill

As the three of us fanned out across the empty arrivals hall at Baghdad International Airport I casually disengaged the safety catch on my East German AK-47.

Talk about the mother of all fuck-ups, said Seamus, his voice echoing over the high ceiling.

He was stabbing the digits on his mobile phone. He glanced about the empty space.

Les Trevellick had moved to his right. He remained expressionless as he looked back.

I was on the left flank with a good view of the runway. Beyond the plate glass windows were the cannibalised remains of some prize specimens of the Iraqi Airways fleet. No other aircraft were in sight.

The rest of the team was outside, three South Africans guarding our two vehicles and humming along to Freedom Radio, the American Forces channel and the only English language radio station we had found. It was ten weeks before Christmas 2003 and Bing Crosby was dreaming of a white Christmas.

In the months to come Baghdad International Airport, or BIAP as it was better known, would be bustling with hundreds of security contractors flying into Iraq under the cold, watchful eyes of armed ex-Gurkhas. Now, in all that vacant space, our footsteps sounded far too loud and the absence of crowds was an almost tangible presence in itself.

We had unloaded our weapons as ordered by the US soldiers at the Coalition checkpoint at the airport entry gate, but had magged up again as we approached the deserted terminal buildings.

The arrivals lounge was far too lavish with its marble trim and polished floors. It was like wandering through an abandoned cathedral, a reminder of something once sacred that had lost its meaning. When the Iraq War ended on 1 May 2003, the first thing the Iraqis did after toppling the statues was remove the name Saddam Hussein from all the airport signs, although you could still see the faded outline where the sun had bleached the stone around the letters. The tyrant had gone, but his presence was everywhere, as strong as ever. Six months had passed since the end of the war, it was October now, the insurgency had begun to gather momentum and enemy attacks were becoming more effective.

Thats why we had been tasked to bring Associated Press reporter Lori Wyatt safely into the Green Zone. This was the interim government, the Coalition Provisional Authoritys (CPA) safety zone, a heavily defended, 10 square kilometre area with a dozen or more of Saddams marble palaces in the heart of the city. Among the palaces you could find all the comforts of home in the shops at the PX the AAFES, or American Army and Air Force Exchange Service not to forget the golden-rimmed toilets of the omnipotent dictator where hairy-arsed GIs from Illinois and Tennessee now went to take a leak.

Although the CPA was in the centre of the area known as the Green Zone, the two terms became synonymous and it was later renamed the International Zone. This was my first tasking since Id arrived in Iraq; our first tasking as a team. And our principal wasnt there.

No one was there.

We were working as private security contractors for Spartan, a UK-based outfit set up by a group of ex-officers, one of a clutch of new security firms with savvy bosses aware that the United States didnt have enough boots on the ground. We were in Iraq for the $500 a day we earned. When President George W. Bush, dressed for battle, announced from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln that the war was over, the White House pushed an $87 billion reconstruction package through Congress; 30 per cent of the money was earmarked for security and everyone wanted a piece.

It had turned Iraq into a gold rush.

The country was awash with new cars, air conditioners, new political parties, newspapers, new computers, Internet porn and money; the dollar bills arrived in shrink-wrapped plastic packs of $500,000 and all our needs from Mars bars at the supermarket to machine guns on the black market were paid for in cash. You could get anything. The money made you hungry for more money. You couldnt help coveting those plastic packs of $500,000 and wondering how you could fit one into your suitcase and take it home. It would certainly solve all my problems. My girlfriend, Krista, and I had a little girl now. We had a new flat with an extra bedroom. The bills had been pouring in.

I had joined the 1st Battalion, the Duke of Wellingtons Regiment as a platoon commander in 1993 after a year at Sandhurst. After six years of attachments and tours including Bosnia, West Belfast and working with American Special Forces, Airborne and US Marines, I resigned my commission to return to my original career path. I had gone up from Winchester, Englands oldest public school, to take law at Brasenose, Oxford. I reckoned in two years as a City solicitor Id be raking it in.

The excitement of civvy street faded in about five minutes and I assumed this was it. This was civvy life. Civilians got up every morning, endured a harrowing commute on Londons filthy and inefficient public transport system, detested their jobs for eight or nine hours, then slogged home in time to fall into bed, just so that they could get up next morning and do it all over again. Day after day. For years. I dont think a day passed without me daydreaming about rejoining the army.

I exaggerate? Maybe, but not much. Only Krista made it all worthwhile and I did everything I could to keep my depression from her. Our daughter Natalie was born in 2000. I loved being a father, but it hit me like a religious revelation just how much I detested working in an office on Wednesday, 19 March 2003, Natalies third birthday. It was the day Coalition Forces (CF) invaded Iraq and with them went the Dukes as part of Operation Telic, the British name for the invasion. I mused on signing up again to join my old regiment, but the war was over three weeks after it started.

The war was over, but the post-war insurgency was growing and private security operators were arriving in Iraq to fight it. There was a fortune to be made. Fortunes were being spent! In the last three weeks we had broken the seals on two plastic packs of $500,000 and spent the lot on equipment, guns, ammunition, vehicles, bribes and baksheesh. Three weeks of spending like millionaires. Now, it was time to put some black ink in the account books. One of the contracts to chaperone reporters around the fractured country had been awarded to Spartan through the US Department of Defense. It was as interesting as PSD missions get and had come at the right moment.

Iraq was the story. Al Qaedas attack on the Twin Towers on 11 September 2001 was one of those defining moments in history. If the Iraq War was a direct response to 9/11 most US soldiers Id met certainly believed it so its implications would affect every aspect of our lives: the price of oil, peace in the Middle East, US relations with Europe, the trust gap between the people and their governments. In Britain, Italy and Spain people had marched in their millions against the war but Blair, Berlusconi and Aznar still followed Bush to Baghdad.