Marianne van Velzen

SHOT DOWN

THE POWERFUL STORY OF WHAT HAPPENED TO MH17 OVER UKRAINE AND THE LIVES OF THOSE WHO WERE ON BOARD

There is a higher court than courts of justice, and that is the court of conscience. It supersedes all other courts.

Mahatma Gandhi

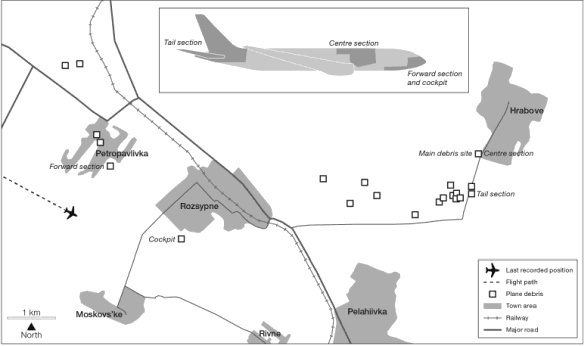

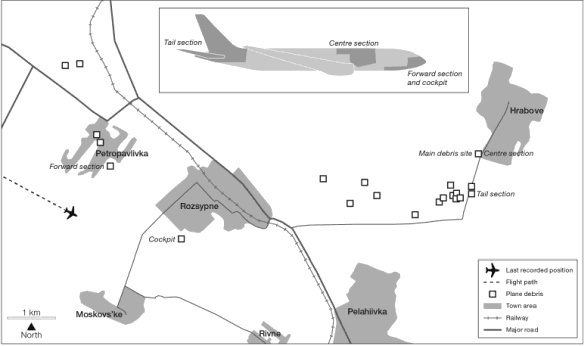

Route taken by MH17

MH17 debris sites

Source: Dutch Safety BoardChapter 1

Amsterdam, 17 July 2014

It was mid-summer, 17 July 2014, and the height of the school holidays in the Netherlands. Everyone in the country appeared to have booked a flight for today. There was a huge shortage of ground personnel at the airport, so it was all hands on deck to get the passengers through transfer, check-in and down to the gates on time to catch their planes.

Renuka Manisha Virangna Birbal had begun her shift earlier that morning at the transfer counter. She worked for one of the companies that helped dispatch passengers at the Netherlands main airport, Schiphol. Appointed to various carriers, today she was working as ground staff for Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17. The night before Renuka had stayed up late, thinking that she would be able to sleep-in the next day. It was supposed to be her day off, but she awoke early in the morning to the sound of her phone. It was incredibly busy at Amsterdams Schiphol airport and she had been rostered on at the last moment. Despite having had only a few hours sleep, Renuka didnt really mind: she would return to bed when she got back to her apartment later that day.

Although the job could be hectic, she loved it, especially when she was able to get the passengers seated according to their various wishes. She had made two football fanatics exceptionally happy after she managed to get them adjacent seats. One was already checked in and the other was still in transit, and they were openly grateful that she had them seated not only next to one another but had also given one of them a window seat.

Just after Renuka finished the transfers, colleagues at the check-in counter asked her for assistance. The passengers waiting patiently in line to be checked in were all dressed lightly. They were a mixed lot, as was the norm on the Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur flightsmainly Dutch but also a large number of Australians, Malays, Indonesians and one or two New Zealanders.

It was a beautiful warm summer morning in Amsterdam. The Dutch so often complained about their weather but Renuka, born in Suriname (the former Dutch colony on the north-eastern coast of South America), never understood their whingeing. They quickly reverted to anxious remarks whenever there was even the slightest hint of rain or clouds, cold or damp; this appeared imbedded in the national character. Renuka had never come across a nation so obsessed with the weather as the Dutch were. This concern surprised her because summers in the small country were more often than not incredibly mild and warm, and also wonderfully bright and clear, quite different to the tropical weather of her homeland. She had come to love summer in the Netherlands.

A family of five with ten pieces of luggage thanked her for managing to get them all seated close to one another and she wished them a wonderful holiday. The youngest child seemed anxious about her suitcase as it disappeared through the transport hatch and she asked Renuka if she would get it back. Renuka smiled and assured the child that her luggage would be waiting for her when she arrived at Kuala Lumpur.

As the next passenger stepped up to the check-in counter, the planes crew members waved to her as they rushed by to drop their bags off at the belt for odd-sized luggage. She waved back as the man next in line handed her his papers and passport. Asking him if he would like a window seat, the burly man nodded. The plane was so full that there were only a few single window seats left. The man smiled, telling her that he was off to Malaysia to start a new life. Her smile in return was sincere, and she wished him good luck as she handed him his boarding pass.

For Renuka the check-in seemed to take hours, but the long line in front of her desk had now almost disappeared and there was only a trickle of stragglers. When one final passenger rushed up to her counter, slightly out of breath, she checked him in quickly before he grabbed his boarding pass with a quick nod of his head and rushed towards the customs line.

The plane was obviously overbooked. For the moment she sent all of the passengers through because there were always no-showspassengers who missed their flight even after they had checked in. But just as she was getting ready to leave her booth, a group of about ten people rushed up. They were travelling together and Renuka immediately knew she would not be able to get such a large party onto the overfull flight. When she made this clear, their faces fell in dismay; one or two of them protested, but most of them just stood there in stunned disappointment.

Asking them to wait, she looked for a flight that could take them all. Emirates, leaving at half past two that afternoon, had enough empty seats to book them in. Because they were beginning to think that they might not be able to get on a flight until the next day, they were more than happy to wait just a couple of hours.

Renuka now headed for Gate 3, knowing there would be an overbooking problem awaiting her there. At the gate she discovered there were hardly any no-shows, and she discussed this with a colleague there. It was always a challenging task to be the staff member who informed checked in passengers that they would not be able to board the plane.

Asking for volunteers to be transferred to another flight was the first and easiest option. Those who did so received handsome compensation, but Renuka knew how difficult it was to persuade passengers to take a later flight. People were always eager to get home or start their holiday, or they had pressing business appointments to meet or urgent duties elsewhere; rarely were they willing to give up their seat on a flight they assumed they were booked onto. The always hard and thankless job of informing people that they would not be able to board the plane was the one part of her work she loathed, as passengers seldom endured their fate graciously. Some put up a fight, she knew from experience, but they usually backed down when the inevitable dawned on them.

Renuka always chose young and visibly fit passengers to be transferred onto a later flight. It was easier for the young to accept and adjust to the disruption of their travel plans than it was for older people or those travelling with children, for whom this was just one more issue to contend with. But first she would ask people to give up their place on the plane voluntarily and then, if the plane still had too many passengers, Renuka and her colleague would have to choose the unfortunates.

She scanned the rows of waiting passengers. An older man with three children had been on the phone for a while. The children pressed themselves against the huge window panes as they pointed at the various planes on the runway. It seemed no parents were accompanying the children, just a man who appeared to be their grandfather.

At the end of a row of passengers waiting at the gate, a boy of about sixteen or so was talking to his mother, his expression one of anxious anticipation. Noticing how his mother listened intently to what he was telling her, Renuka could read in her hand movements and reassuring smiles that she was trying to set her sons mind at ease. During her years of working at the airport she had learned to read facial expressions and body movements. It was part of her job.

Route taken by MH17

Route taken by MH17 MH17 debris sitesSource: Dutch Safety Board

MH17 debris sitesSource: Dutch Safety Board