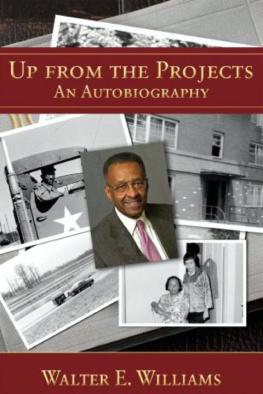

UP FROM THE PROJECTS

To the Memory of Connie

and to Devyn, the dear daughter she gave me.

Contents

ix

i

Preface

DESPITE NUMEROUS PAST SUGGESTIONS THAT I WRITE an autobiography, I have long resisted doing so. That's partly because I never thought autobiographies were important in the larger scheme of things. Also, partly because of the press of so many other commitments, I decided not to take the time.

What prompts me now is a combination of factors, not the least of which was the urging by my now-deceased wife of48 years, Connie, and our daughter, Devyn. In her loving and polite way, Devyn advised that if an autobiography were in my plans at all, it should be written now lest it end up as a work of fiction. That's a nice way to communicate to one's father that at age 74, one's memory is not what it used to be and that prospects for improvement are not in the cards.

Dr. Thomas Sowell, my longtime friend and colleague, suggested another important reason for an autobiography: there has been considerable "publicness" to my life. What I've done, said, and written, and the positions I have taken challenging conventional wisdom, have angered and threatened the agendas of many people. I've always given little thought to the possibility of offending critics and contravening political correctness, and have called things as I have seen them. With so many "revisionist historians" around, it's worthwhile for me to set the record straight about my past and, in the process, discuss some of the general past, particularly as it relates to ordinary black people.

An autobiography permits me to talk about my life as it actually was, or as I recall it, as opposed to risking having someone else-friend or foe-make untruthful statements, wrong assumptions, and distortions. In that regard, I'm reminded of the angry response that former Secretary of Health Education and Welfare Patricia Roberts Harris wrote in response to Dr. Sowell's two-part series, "Blacker Than Thou," published in 1981 in The Washington Post. Assessing his criticisms of black civil rights leaders, Ms. Harris said, "People like Sowell and Williams are middle class. They don't know what it is to be poor." Nothing is wrong with being middle class.

But both Sowell and I were born into very poor families, as were most blacks who are now as old as we are. A reader of Patricia Harris' remarks would have had no reason or information to challenge her assertions that Sowell and Williams "don't know what poverty is."

While starting out poor, my life, like that of so many other Americans, both black and white, illustrates one of the many great things about our country: just because you know where a person ended up in life doesn't mean you know with any certainty where he began. Although I do not want to appear egotistical, neither am I a shrinking violet. I can say with considerable certainty that I have amassed achievements, earned income, and accumulated wealth to an extent that would have been unfathomable by my ancestors.

How did that happen? Because unlike so many other societies around the world, in this country one needn't start out at, or anywhere near, the top in order to eventually reach it. That's the kind of economic mobility that is the envy of the world. It helps explain why the number one destination of people around the world, if they could have their way, would be America.

This autobiography is not intended to be a complete, tell-all story of my life. Instead, I have tried to capture some of its highlights and turning points, and to contrast growing up black and poor in the 1940s and 1 5os to the same experience today.

CHAPTER ONE

Starting Out

FIVE YEARS OLD IS MY EARLIEST MEMORY; that was in 1941. My sister Catherine and I were sitting on a bench in the hallway of a somewhatornate building with high ceilings, and we marveled at a huge painting of three galloping white horses. While I can't say for certain, my best guess is that it was either that of the Philadelphia board of education at 21st and Parkway or of the Andrew Hamilton Elementary School at 57th and Spruce Street. My mother was in the office, enrolling us in elementary school.

We lived in a lower-middle-class, mixed, but predominantly black neighborhood at 5565 Ludlow Street in West Philadelphia. The grade school nearest our house was Hoffman elementary, just a block or so away. My mother thought we'd receive a better education at Andrew Hamilton, which was in our district but six blocks away. Hoffman had a relatively large black student population. Hamilton had no black students but many Jews. School authorities therefore encouraged my mother to enroll us at Hoffman, because they thought we'd feel more comfortable there.

Mom argued that Hamilton was within our school district and insisted that we be enrolled there. She knew we were eligible to attend Hamilton, because its students included the daughter and son of a Jewish merchant, whose business and upstairs living quarters were located just around the corner from us, at 56th and Market Streets.

Mom was a forceful yet dignified woman who didn't easily take no for an answer. I don't know what she said or threatened, but that fall we attended Hamilton, I in the first grade and my sister in kindergarten.

Though we were the first black students to enroll at Hamilton, we encountered no racial problems. The teachers treated us nicely, and so did the students. I do remember bringing a note or some other notice home to my mother saying that I had been selected to play a part in a minstrel play. My mother told me that she wasn't going to give me permission to be in the play. Instead, she declared, they could put burnt cork on the face of one of the white children.

My years at Hamilton corresponded with those of World War II. On certain days, there would be paper drives to help the war effort. That's when many of Hamilton's students would go from house to house collecting old newspapers. The patriotic desire to defeat Hitler and Hideki Tojo was one of our incentives; but another was that the class with the highest pile of newspapers, stacked against the schoolyard fence, would be dismissed from classes early. While my class won some of the time, I didn't enjoy the early-dismissal treat. My mother's instructions were to go to school and come home with my sister, who was one year younger than I. As a result, when my class won the newspaper-collection prize, I spent time in the school library until my sister's class was dismissed.

My mother worked at least a couple days a week as a domestic servant. During those days, children came home for lunch. Hamilton didn't have a lunchroom, as I recall. So on the days my mother worked, she'd leave baked beans, Spam, or some other canned goods on a floor-heater vent-so that we'd have a reasonably warm lunch. She forbade us to light the stove. I guess she feared that we might burn ourselves or set the house on fire.