It does seem hard that our earth may be a far better place than we have yet discovered, and that peace and content may be only round the corner, yet that somehow our song of praise is prevented, or does not go well with Hesperus, unlike that of a silly bird.

H. M. Tomlinson, The Face of the Earth

T his book would have taken me half as long to write if it were not for one fact: most of it was composed with a starling perched on my shoulder. Or at least in the vicinity of my shoulder. Sometimes she was standing on top of my head. Sometimes she was nudging the tips of my fingers as they attempted to tap the computer keys. Sometimes she was defoliating the Post-it notes from books where I had carefully placed them to mark passages essential to the chapter I was working onshe would stand there in a cloud of tiny pink and yellow papers with an expression on her intelligent face that I could only read as pleased. She pooped on my screen. She pooped in my hair. Sometimes she would watch, with me, the chickadees that came to my window feeder to nibble the sunflower seeds I left for them. Sometimes she would look me in the eye and say, Hi, honey! Clear as day. Hi, Carmen, I would whisper back to her. Sometimes, tired of all these things and seemingly unable to come up with a new way to entertain herself or pester me, she would stand close to my neck, tunnel beneath my hair, and nestle down, covering her warm little feet with her soft breast feathers, so close to my ear that I could hear her heartbeat. She would close her eyes and fall into a light bird sleep.

It sounds like a sweet scene, but there is a conflict at its center. I am a nature writer, a birdwatcher, and a committed wildlife advocate, so the fact that I have lovingly raised a European starling in my living room is something of a confession. In conservation circles, starlings are easily the most despised birds in all of North America, and with good reason. They are a ubiquitous, nonnative, invasive species that feasts insatiably upon agricultural crops, invades sensitive habitats, outcompetes native birds for food and nest sites, and creates way too much poop. Millions of starlings have spread across the continent since they were introduced from England into New Yorks Central Park one hundred and thirty years ago.

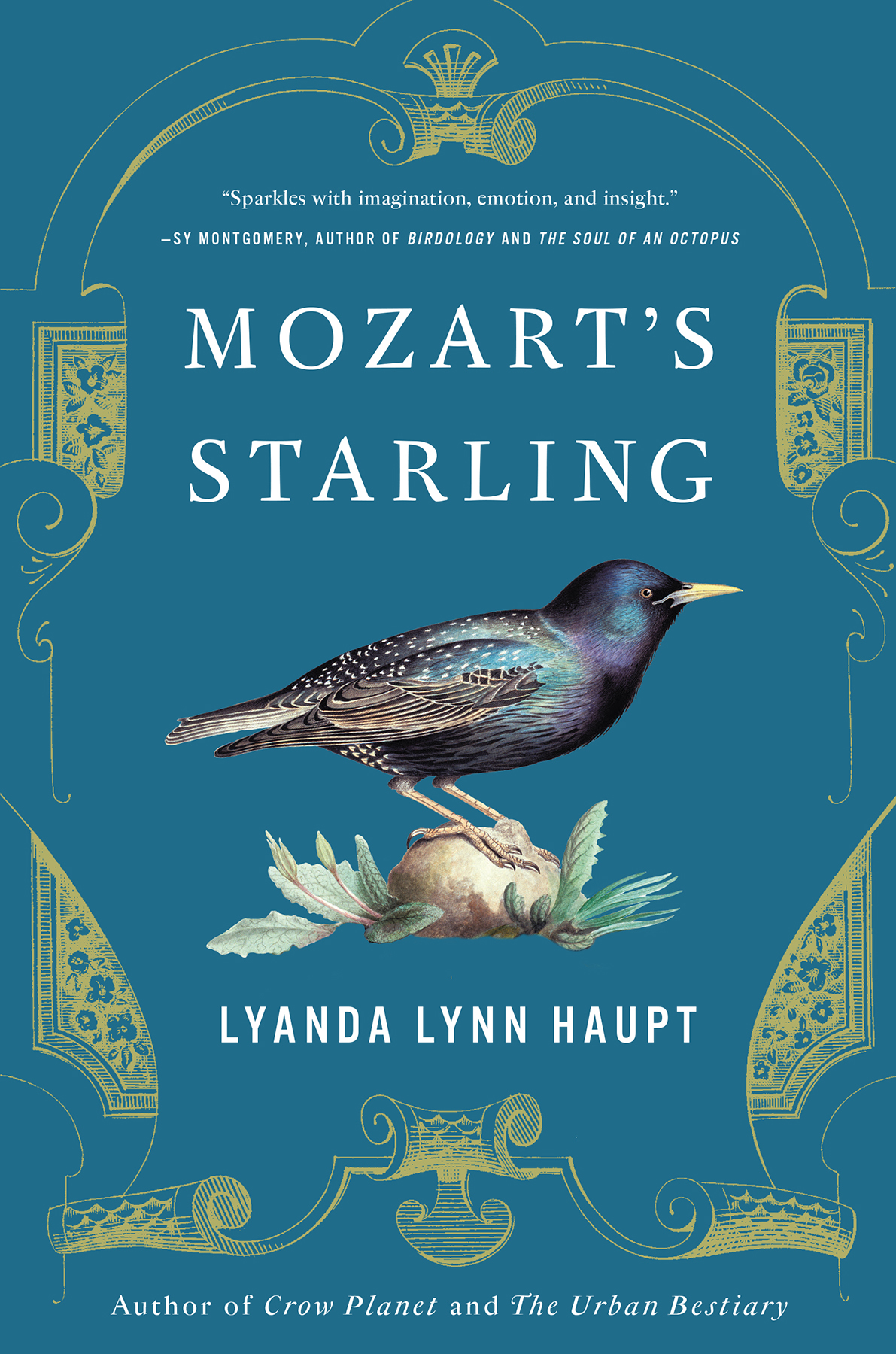

An adult starling is about eight and a half inches from tip to tail, a fair bit larger than a sparrow but still smaller than a robin, with iridescent black feathers and a long, sharp, pointed bill. Just over a hundred and fifty years before the first starlings appeared in Central Park, the Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus had placed the species within his emerging avian taxonomy and christened it with the Latinized name we still use: Sturnus vulgaris. Sturnus for star, referring to the shape of the bird in flight, with its When Linnaeus named the bird, it was simply part of the European landscape and had not spread across the waters. There was no controversy surrounding the species; it was just a pretty bird. Starlings are now one of the most pervasive birds in North America, and there are so many that no one can count them; estimates run to about two hundred million. Ecologically, their presence here lies on a scale somewhere between highly unfortunate and utterly disastrous.

In The Birdists Rules of Birding, a National Audubon Society blog by environmental journalist Nicholas Lund, one of the primary rules is actually Its Okay to Hate Starlings. Sometimes beginning birders in the first flush of bird-love believe that it is a requirement of their newfound vocation to be enamored of all feathered creatures. But as we learn more, writes Lund, our relationships with various species become more nuanced. Some species are universally loved; who wouldnt feel happy in the presence of a cheerful black-capped chickadee? But once we become more informed about starlings, we begin to feel an inner dissonance. Lund tells birders who are first experiencing such confusion not to feel guilty: Its okay to hate certain species healthy, even. I suggest you start with European Starlings. In addition to the issues with starlings Ive listed, Lund adds: Theyre loud and annoying, and theyre everywhere.

Its true; among those who know a little about North American birds, starlings are not just disliked, theyre outright hated. In The Thing with Feathers: The Surprising Lives of Birds and What They Reveal About Being Human, birder and journalist Noah Strycker (famous for seeing more species of birds on earth in one year than anyone, ever) writes, If you Google Americas most hated bird, all of the top results refer to starlings. Such universal agreement is rare in matters of opinion, but on this everyone seems to concur: Starlings are rats with wings. Birders typically keep lists of the species they see on a field trip, but many dont even include the invasive starling on their tallies. Ornithological writer and blogger Chris Petrak does list them, not because he is glad to spot them but because he is interested in those rare occasions when I can go almost an entire day without seeing a starling, and those even rarer days when I dont see one at all. The joy of a starling-less list. He goes on to back up Strycker: Bird lover or not, the starling is not a loved bird. In fact, it is without a doubt the most hated bird in America.