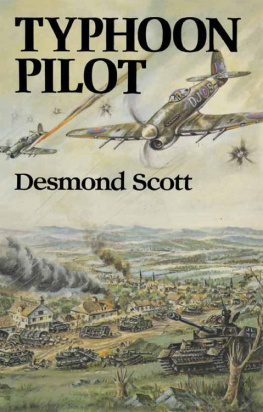

TYPHOON PILOT

TYPHOON PILOT

by

DESMOND SCOTT

First Published in Great Britain 1982 by

Leo Cooper in association with

Martin Secker & Warburg Limited

54 Poland Street, London W1V 3DF

Copyright 1982 Desmond Scott

ISBN: 0 436 44428 3

Filmset by Northumberland Press Ltd,

Gateshead, Tyne and Wear

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Richard Clay (The Chaucer Press) Ltd, Bungay, Suffolk

Contents

Note: The endpaper photographs and those marked IWM in the 8 page section are reproduced by permission of the Imperial War Museum.

by

Air Vice-Marshal W. J. Crisham, CB, CBE, RAF (Rtd.)

This is a story about heroes, a record of their collective courage and skill, alight with the fierce enthusiasm of their young leader, Desmond Scott.

Scottiehimself a brilliantly able and magnificent pilotforged his closely-knit team of young New Zealand pilots into a superb fighting unit, capable of meeting constantly changing operational needs with matchless efficiency.

Scotties operations, whether he was squadron commander or wing leader, bore the stamp of immaculate planning and execution. He was always concerned for the safety of his pilots and other aircrew, especially those who had the misfortune to be downed in the sea. Indeed, his rescue operations dangerously close to the enemy coast were cast in the heroic mould and gave a tremendous boost to morale.

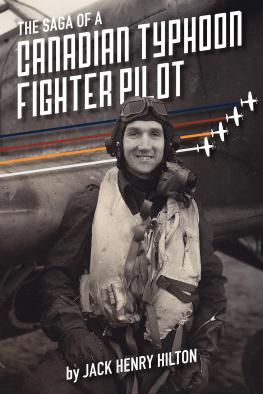

The Tangmere Typhoons were extremely active during the buildup prior to the Normandy invasion, primarily in the neutralization of flying bomb and other missile-launching sites, and later in the destruction of heavily defended radar stations before D-Day. These vital tasks were successfully carried out.

On the Normandy bridgehead, with Scottie and his Tangmere Typhoon squadrons now in the Second Tactical Air Force, the rocket-firing Typhoons smashed the enemys tanks and road convoys at Falaise and hustled him homewards via the Channel Ports and the Scheldt Estuary to the Rhine.

The job was done!

To the dauntless nothing is denied.

W. J. Crisham

Whereas the Spitfire always behaved like a well-mannered thoroughbred, on first acquaintance the Typhoon reminded me of a half-draught: a low-bred cart horse, whose pedigree had received a sharp infusion of hot-headed sprinters blood. It lacked finesse, and was a tiger to argue. Mastering it was akin to subduing the bully in a barroom brawl. Once captured, you held a firm rein, for getting airborne was like riding the wild wind. One casual crack of the whip, and the jockey was almost left behind. But like the human race, the Typhoon had its good points too. In sharing the dangerous skies above Hitlers Europe I had good reason to respect its stout-hearted qualities. It gave no quarter; expected none. It carried me into the heart of the holocaustand even when gravely wounded delivered me from its flames. As a young pilot I grew not only to respect the Typhoon, but also to trusteven to loveit.

After the death of the Third Reich, silently and unobtrusively the Typhoons flew off in obscurity. But I shall never forget them. Not ever, for by the wars end they had become part of me.

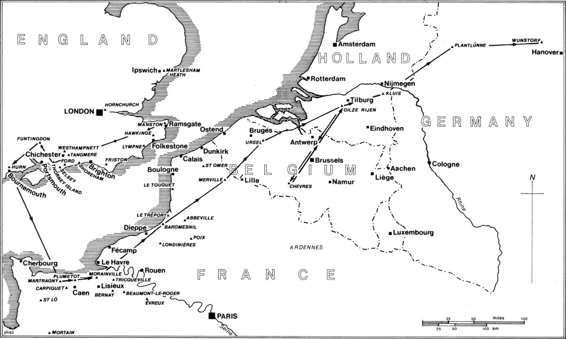

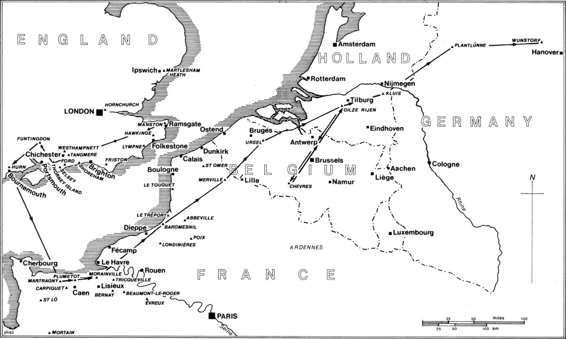

The travels of Desmond Scott and his New Zealand Squadrons.

I was brought up with horses, and it was therefore only natural, when I left grammar school, that I joined the Territorial Army and became a trooper in our Canterbury Yeomanry Cavalry. The rattle of spurs, the mature conversation of older men and the orchestrated performance of our horses, was a welcome change from the classroom, but life in the cavalry had its sore points too, as I was quick to learn.

One day while on manoeuvres, our troop was attacked by two Bristol Fighter planes, ancient relics of the First World War, and flown by pilots of the New Zealand Air Force. As they swooped low over our heads, my horse, which normally had the heart of a lion, took the bit in his teeth and bolted. One of the pilots, savouring my predicament, persistently pressed home his attacks and, several fences and a few ditches later, Toby and I parted company. To add insult to injury, I received an impolite hand signal from above, and decided there and then, if I was to fight my wars in a sitting position I would need a steed that could not only fly, but outsprint any opposition.

When our annual camp disbanded, I began taking flying lessons in an Aero Club Gypsy Moth, but in those days dual instruction was 30 shillings an hour, and consequently my progress was expensive and slow. However, after a total of six and a half hours dual instruction, I managed to go solo, and was saved from my creditors by a stroke of good forturne. Just prior to Hitlers indiscretions, our government introduced a scheme in which successful applicants were given 40 hours flying at the taxpayers expense. Much to my surprise, my application was successful. About the same time that I had completed my 40 hours, England declared war on Germany. I promptly received a registered letter from our Air Department reminding me of a small clause at the bottom of our contract. Thus I was compelled to leave the cavalry and became a member of His Majestys Junior Service, but it was not until August, 1940, and after much flying in antiquated Fairey Gordons, that I finally set sail for the other side of the world to take my place among the survivors of Churchills few.

Flying Hurricanes was a far cry from piloting slow old biplanes, but again I was lucky, for my first operational posting was to the Orkney Islands, a relatively quiet area in Hitlers blitz. A few weeks protecting part of the British Fleet at Scapa Flow gave me the opportunity to gain the necessary experience that helped me to survive in No 11 Group, the RAFs hot spot, which included London and most of the south coast. It was in this prestigious company that I spent the following four years.

Hurricanes were already the work horse of Fighter Command and for nearly two years I piloted them on almost every type of operation. There were many nights when I flew above a burning London. I participated in daylight shipping attacks along the French and Belgian coasts and acted as close escort to Blenheim and Stirling bombers, on raids that were aptly code-named Circuses. I survived a mid-air collision with one of No 23 Squadrons Havocs, and it was also from a long-range Hurricane that I watched Cologne explode, as a thousand RAF bombers emptied their war load from the night sky. As with our adversaries, our offensive operations were often more spectacular than successful. Nonetheless, all were hazardous, and the experience gained by those who survived was always sorely won.

When I had completed the equivalent of two operational tours, I began to feel the strain and did not object when I was promoted to Squadron Leader and posted on rest to a temporary staff appointment at Bentley Priory, the headquarters of Fighter Command.

1

Bentley Priory

No sane pilot would have wanted a posting to a Typhoon squadron in the winter of 1942. New types of aircraft always had their faults, but the Typhoon had far more than most. For a start, its huge 24-cylinder Napier Sabre liquid-cooled engine was far from dependable. If it stopped dead while you were in the air, you were faced with two alternativesover the side, or the gliding angle of a seven-ton brick. Even worse was its tail section. For reasons which even the experts could not fathom, several Typhoons had shed their tails and buried themselves and their pilots in very deep holes.