Contents

ABOUT THE BOOK

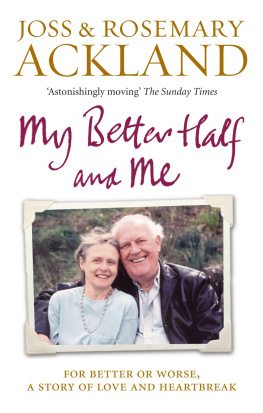

My Better Half and Me is the story of a very old-fashioned love affair, and of fifty years of lives fully lived through joy and tragedy.

ROSEMARY ACKLAND began writing her diary as a child in Africa and continued it up to her eventual death from motor neurone disease, 58 years later. Here, Joss adds his rich recollections to complete their shared story. From the excitement of Josss burgeoning acting career and joy at the births of their seven children, to the terrible fire that consumed their house and the tragic death of their eldest son, Rosemarys simple, heartfelt writing tells of enduring love through turbulent times.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joss Ackland CBE was born in 1928 in London. Trained as an actor, he has appeared in more than 130 films, and countless theatre, alongside such luminaries as Dame Judi Dench, Ingrid Bergman and Lauren Bacall. However, his first priority was always his wife Rosemary, and now their seven children and 33 grandchildren.

My Better Half and Me

A Love Affair That Lasted Fifty Years

Joss & Rosemary Ackland

To our family

PREFACE

Towards the end of the Second World War, fifteen-year-old Rosemary Kirkcaldy started to keep a diary. She kept it, intermittently, over a period of fifty-eight years a diary with which she communicated, in a matter-of-fact, dispassionate manner, the events of the day. During our long partnership, the thought never crossed my mind that I might read it nor did she suggest it. It was only towards the end of her life, suffering motor neurone disease, when she needed my help to hold her pen that I read any of her words. I found the cool, laid-back approach to an extraordinary life of fun, poverty, success, tragedy and excitement, both touching, and at times very funny. When I asked her if I could see about getting it published unable to move or speak, she smiled and nodded her assent.

For six years after her death I spent all my free time copying and editing the multitude of words, from diaries of various shapes and sizes. I wrote about a great deal of our life in an autobiography which was published in the early eighties, so I now have included some experiences from her point of view, and to fill in the gaps when she was too desperate or too busy to write.

The changes that have taken place on this planet in the fifty-eight years since Rosemary started her diary are greater than at any time since man first walked the earth even the years after the Industrial Revolution. Class distinction has evaporated, equality of the sexes is nearer and homosexuality is generally accepted. Racism still exists, but only with the fading minority. However we are still primitive creatures, and today we have such colossal powers of destruction that once the wrong button is pressed we could be back where we began. We are still immature, and if we are without morals and faith we are liable to self-destruct. We know nothing of the moment before we emerge from the womb and nothing after we leave the door at the end of life.

Our faiths have multiplied, and these faiths usually depend on the piece of land that we inhabit. Sadly this has often led to violence, hate and war. All religions can create some balance of self-discipline. As long as they advocate love of fellow man they can guide us. We exist for a purpose, but what that purpose is no one knows. Throughout the ages there have always been exceptional leaders to drive us forward. During the last fifty years Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela and others have led the way in removing racial prejudice. To go forward it is important to have faith but to despise or reject those whose faith is different is a dangerous arrogance. With the constant threat of war and terrorism, in spite of all our scientific and technological advances, we are still very primitive creatures. We exist for a purpose but no one knows what that purpose is. Rosemary followed the Christian path, and whatever path she took I knew I should follow.

It is very important that the world progresses forward from one generation to another. These days, once the young reach their teens, it is not easy. When Rosemary and I grew up, you were a child and then you were an adult there was no period in between no time to balance precariously on that tightrope of uncertain confidence. Today there are few apprentices and no mentors, and very few of the young have any conception what we were like at their age. We are totally different creatures. There are times I feel I have landed on Mars; but then I realise that I am the Martian.

Rosemary started her diary in 1945 at her home in Malawi in the heart of Central Africa, and I was in London training to be an actor. This was six years before we met, and our love story began.

And it is a love story. In those days there were no nuptial agreements no preparing for divorce a before joining together in marriage. And sixty years ago less was considerably more the joy of the first kiss, the pleasure of touch, the longing for the unobtainable and when the unobtainable was obtained more was considerably more. Then two hearts really could start beating as one.

And it was not long before our two hearts did beat as one. We became soulmates. It was not a generous act to see our partner happy. Our satisfaction was achieved from the others pleasure. We loved each other more than we loved ourselves. When I was working abroad without Rosemary, I could not find real joy and satisfaction in any location until I returned with her beside me.

Our lives have not been ordinary, but Rosemary always accepted everything with a calm detachment. One minute she would be doing household chores and picking up the children and the next popping off to Rio as if she was nipping round the corner to buy bread. She coped with disaster and trauma with patience, cool stoic acceptance and enormous courage. Even when our house burnt down, with no one else able to help, she ran through the flames, and saved our children.

Today I do not have the confidence to return to the theatre, because Rosemary and I always worked together tackling a play, and it was always her strength and her calm quiet assurance that energised me, and moved me forward.

By the time Rosemary developed motor neurone disease, unable to speak or move, it was only with her diary with that she was able to communicate, and so I have included these last two years in more detail.

EARLY DAYS

IN 1945, WHEN she first started her diary, Rosemary and I were at the opposite ends of the earth. She was in Nyasaland Malawi and I was in England. Our backgrounds were very different. I was one of three children. My father was Norman Ackland, an Irish journalist, who, after seducing his parents maid, had been sent over as a remittance man to England to stay with his aunt Annie, in London. There he seduced his aunts maid, Ruth, and so my older brother, Paddy, was born.

Ruth then spent her life living in rented basement flats. My father went off to war in 1914 and when he returned, he married her, and then went off again. Once in a while he would drop in, and after six years my sister Barbara was born. He was next around seven years later and then I dropped from the womb. I was due to be born in Saint Mary Abbotts Hospital in Kensington, but there had been a confusion of babies two mothers had been given the wrong child by mistake so my mother fled from the hospital in her nightdress, in the middle of the night, and I was born in our basement flat near Ladbroke Grove.

In 1939 we moved to yet another basement flat in Stoke Newington where, at the age of eleven, I was due to start senior school at Dame Alice Owens, the only school where I had managed to pass the entrance exam. Before I started school there, we had a chance to see the sea for the first time when we boarded HMS

Next page