Big thanks to the team of people, all of them essential, who helped put this book together: Sandy Grant, Lyn Tranter, Emma Schwarcz, Megan Taylor, Warwick Franks, Chris Ryan, Ross Dundas, Luke Causby, Josh Durham, Lynne Hamilton, Jane Winning and Keiran Rogers.

Also to the colleagues, both on tour and in various offices, who turned up the brightness on the business of writing about cricket.

Among many others, special thanks to Greg Baum, Martin Blake, Ken Casellas, Ben Coady, Malcolm Conn, Robert Craddock, Peter Deeley, Michael Donaldson, Michael Koslowski, Tim Lane, Jim Maxwell, Steve Meacham, Fazeer Mohammed, Mark Ray, Peter Roebuck, Chris Ryan (again), Will Swanton, Phil Wilkins and most of all Mike Coward.

The line referring to Allan Border and his cape is gratefully adapted from Les Carlyon.

CONTENTS

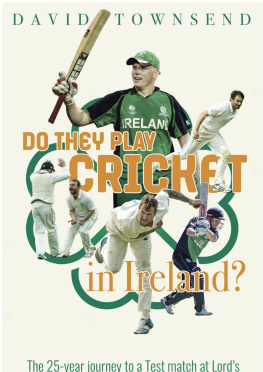

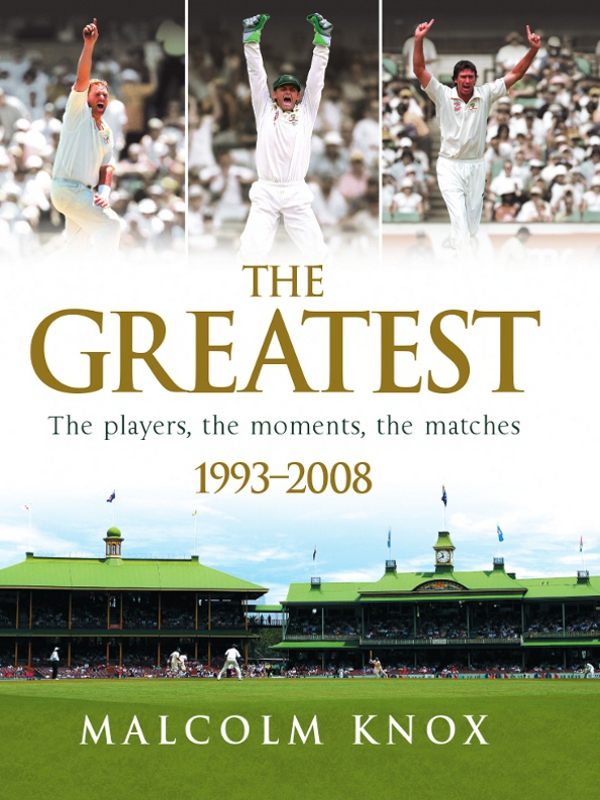

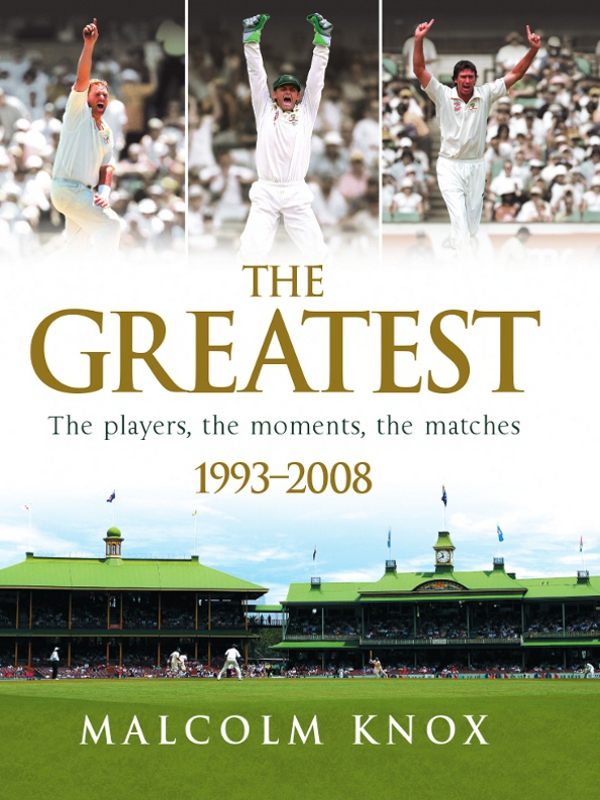

This is a book about cricket. Specifically, it is a book about cricket matches involving Australia since the early 1990s. Most are Test matches, but there have also been occasions in the past fifteen or sixteen years when a limited-overs international has risen out of the amnesic swamp to live in the open air of memory, as fresh as yesterday. There are no Twenty20 matches in this account. Like pulp fiction or Chinese food, the shorter forms of cricket can absorb and satisfy us while they have our attention, but afterwards tend to leave us hungry.

Six of the Test matches Australia played between 1993 and 2000 were included in Wisdens 100 Matches of the Twentieth Century. Several more they played between 2000 and 2008 will no doubt be in Wisdens 100 Matches of the Twenty-first. The Australian team, in this period, aroused many conflicting moods among cricket followers but indifference was not one of them. Whatever else they were, these Australian teams were constantly magnetic. In the physical sense if not always the aesthetic, they exerted an irresistible power of attraction.

Those who remember the 1980s will recall that Test cricket was quite often a dull spectacle. Scoring rates were low, bowling was attritional, and many Test matches did not just peter out to dull draws, but even petered out to dull wins and losses. By the early 1990s there was little to promise the new decade wouldnt provide more of the same. In fact, Australian Test cricket since Bradmans time was more often than not a drab affair, punctuated by periodic flurries of excitement 1958 to 1961, 1972 to 1977 that were all the more memorable for their rarity. If Australian cricket followers had been told in 1991 or 1992 that we were about to be gripped by the revival of leg-spin bowling, a new variety of dynamic seam, swing and pace, at times unthinkable acts of athleticism in the field, and scoring rates regularly exceeding four runs an over, we would not have believed it until we had seen it. If told that this new era would feature Test matches won with a six off the last ball, World Cup finals won with run rates of seven an over, series decided by margins of one run, two runs and one wicket, not to mention potboilers involving bookmakers, strikes, chucking, drugs, organised crime and sext messages, we would have rolled our eyes and said we were not interested in the exaggerations of escapist fiction.

The timespan of this book, 1993 to 2008, has been chosen not because fifteen years is a nice round figure. The primary reason is that Australia did not lose a Test series at home between 1993, when the West Indies won the last of its five straight undefeated series in Australia (Australia managed a draw in 198182), and 2008, when Graeme Smiths South Africans sealed a two-Test lead at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. During that time, Australia was seldom beaten overseas either: 1994 in Pakistan; 1996, 1998 and 2001 in India; 1999 in Sri Lanka and 2005 in England were the only lost series. It is some record.

The secondary reason to choose 1993 and 2008 as bookends is that those years coincided more or less with the Test careers of the two most influential players of the era. Shane Warne played for Australia from January 1992 to January 2007, Glenn McGrath from December 1993 to April 2007. Coincidence is of course the wrong word. The Australian golden era was Warne and McGrath. Their personalities, and those of a host of other players both major and minor, Australian and foreign, combine with the contests on the field to provide the strokes of colour between the hard outlines of events themselves.

In Gideon Haighs view, trying to pick and weigh up Great Test Matches is the ultimate cricket fogey topic. This book, then, is for, and possibly by, the ultimate cricket fogey. This is nothing to be embarrassed about. We have increasing cause to remember, and talk about, and reconstruct the drama of, great Test matches. When I was a touring cricket newspaper journalist in the 1990s, print media had long renounced the first task of traditional journalism. We were no longer writing the first draft of history. We were writing about injuries, forecasts, threats, scandals and politics. Why? The orthodox belief was that television and radio were doing such a good job of bringing audiences the drama of the game itself that there was little space left for the printed word to revisit what had happened on the field. We had to do more. Instead of recounting what had happened in the game, we had to give readers extra value on top of what they already knew of innings, scores, wickets and results. So the accent for print media became throwing forward, or producing stories that would be relevant the next day. This was how an interview in which Mark Taylor or Shane Warne said they were looking forward to pushing home their psychological edge over an opponent came to take precedence over the hundred runs Taylor may have scored, or the six wickets Warne had taken, that very day. This was how the worries about Glenn McGraths groin or Steve Waughs hamstring affecting their availability for the next Test match pushed aside a written prose record of what they had done in the present one.

I always found this an unnecessary evil of the coverage. Instead of giving more, I sensed that paradoxically we were giving less. By writing for tomorrow and skating over today, we were actually increasing the ephemerality of what we were providing. Nothing obsolesces as quickly as a forecast. Once the game has started, who cares whether Warne had been in doubt with a stiff bowling finger? I was far from the most skilful practitioner of modern sports journalism, because what happened off the field never interested me half as much as what happened on it. Speculating on tomorrows play never held my interest half as much as ruminating on todays.

As a child, I had loved nothing more after going out to the SCG to watch a days international cricket than to stay up late that night to watch the highlights replayed on television. The next morning, I lunged for the newspaper reports. If they rehashed everything I had seen, all the better. Just because I had lived through it once didnt mean I didnt want to live through it again. And again.

The selection of matches in this book is not a trainspotting exercise for us fogeys to dispute over our thumbed copies of Wisden. Some of Australias great Test matches receive only passing mention here: against Sri Lanka in Galle in 2004, against Bangladesh in Fatullah in 2006, against New Zealand in Wellington in 2005, for instance. Conversely, there are some matches recounted in detail, such as that against England at The Oval in 2001, which were not among the great Tests in themselves. Rather, the guiding principle is to serve the dramatic needs of the story of Australian cricket through those years. The Test matches included in this book are the plot points around which that story pivots. Many of them, inevitably, also happen to be the greatest cricket contests of the time.

Next page