KICK AND RUN

MEMOIR WITH SOCCER BALL

BY

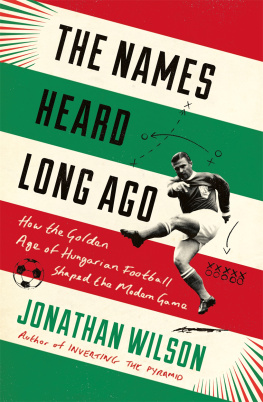

JONATHAN WILSON

Parts of this memoir first appeared in slightly different form in the following publications: The New Yorker, The Paris Review Daily, Agni, Maggid, The Jerusalem Review, Who We Are, Promised Lands, The Jewish Quarterly and Jbooks.

Thanks to supporters from:

Tottenham: James Wilson, Gabriel Wilson, Adam Wilson, Sharon Kaitz, Michael Stephenson, Lawrence Gerlis, Michael Sheldon.

Other teams: Ben Wilson (Oxford United) William Grossman (West Ham) John Bailey (Sheffield Wednesday) Josip Novakovich, and Nicols Livon-Navarro (Barcelona) Timon Sthler (Bayern Munich) Clive Sinclair (Luton) Mike Emery (Crystal Palace).

Management: Jennifer Alise Drew, Gail Hochman, Stephanie Duncan, Anne Putnam, Ellen Golding.

Referee: Richard Charkin

Jonathan Wilsons fiction, essays, and reviews have appeared in The New Yorker, ARTnews, Esquire, The New York Times Magazine, The New York Times Book Review, Tablet, The Times Literary Supplement, Best Short Stories, The Best of Best Short Stories, The Paris Review Daily, and Best American Short Stories, among other publications. In 1994 he received a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship. His work has been translated into many languages including Dutch, Hebrew, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian and Chinese.

Wilson is the author of seven previous books: the novels The Hiding Room (Viking 1994), runner up for the JQ Wingate Prize, and A Palestine Affair (Pantheon 2003), a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, Barnes and Noble Discovery finalist and runner up for the 2004 National Jewish Book Award; two collections of short stories, Schoom (Penguin 1993) and An Ambulance is on the Way: Stories of Men in Trouble (Pantheon 2004); two critical works on the fiction of Saul Bellow; and a biography, Marc Chagall (Nextbook/Schocken 2007), runner-up for the 2007 National Jewish Book Award. Kick and Run is his eighth book and his first work of memoir.

Wilson currently lives in Massachusetts, where he is Fletcher Professor of Rhetoric and Debate, Professor of English and Director of the Center for the Humanities at Tufts University.

For John Bailey

My over-excitement was beyond all description

Jules Verne

Kick and Run is a work of memoir. It reflects the authors present recollection of his experiences over a period of many years. Certain names, locations and identifying characteristics have been changed. Dialogue and events have been recreated from memory and, in some cases, have been compressed to convey the substance of what was said or what occurred.

Contents

In May and June of 2006 I spent a few weeks in the almost unbearably charming French village of Talloires, where Churchill liked to summer, and from whose terraced hillside Czanne once painted a castle that sits on the opposite side of Lake Annecy. It is true that I was drinking a lot of wine on those chilly Haute-Savoie nights, but alcohol, it turned out, was not what was precipitating my weekly falls from bed.

Heres the thing: each time I catapulted to the floor I was mid-dream, executing a spectacular soccer move, an overhead or scissor kick, a delirious pivot and shoot, a spectacular leap over two defenders. My muscles, which were supposed to be asleep, twitched into action, and fabulous spasms sent me flying, arms and legs akimbo, into the unforgiving furniture of my bedroom. Once I cracked my head so violently on the bedside table that I was rendered briefly unconscious, as if Manny Pacquiao had struck me with a fierce left hook.

I had suspected for some time that soccer was deeply embedded in my unconscious, but I had not realized how frequently it populated my dreams until its fitful eruptions abbreviated my sleep.

Back home in the States, the episodes increased in frequency, such that after a few months I was sleeping like a big baby, with bumpers in the shape of numerous pillows placed around the bed in case I threw myself into action during some vital World Cup game. This continued for two years until one night I moved right instead of left and inadvertently whacked my wife in the head with a flying elbow. I made an appointment with my doctor.

A few weeks before I crashed out for the first time in Talloires, I had begun to take small daily doses of the anti-depressant Zoloft; this medication had been prescribed to me by a shrink who, Id felt from the beginning of our acquaintance, did not like me very much. She seemed to disapprove of everything I said and did, and, like my older brothers before her, generally sided with whomever it was that I was whining about.

I was only with this shrink, lets call her Dr. Scold, because after seven years of analysis I had finally told my previous shrink, Dr. Kind, how much I hated her knee-high stockings, published a story in Esquire that reiterated the session, and then felt so guilty that Id decided to quit. Dr. Kind was of the opinion that pretty much everything I directed at her was intended for my mother. This may well have been so, although the possibility also exists that Freud, as the novelist Saul Bellow once remarked, was a nudnik who subjugated us with powerful metaphors.

Before I went to see my doctor, the respected author of a self-published guide to good living called Dont Worry, Be Healthy, I searched WebMD for an explanation of my symptoms, and what I came up with was illuminating. Certain SSRI drugs, of which Zoloft is one, have been known to bring on neo-epileptic symptoms during REM sleep, like those I had experienced while playing dream-soccer. I described what I had discovered to my doctor, and he said, Stop taking the Zoloft. Dr. Scold weaned me slowly and carefully off the little blue pills, and my symptoms gradually disappeared. When I had stopped falling out of bed altogether, I e-mailed Dr. Scold and told her that I thought I might now proceed without her services. True to form, she never replied.

Sometimes I miss my extravagant propulsions. I dont play soccer anymore, and if I dream of it I rarely remember having done so. But I would guess that, unless things have changed dramatically, many of my sleeping hours, like a great deal of my waking hours, are spent observing the same field of dreams, 100 yards by 50 yards, twenty-two players, white lines, a center circle, goalposts, a net, and, waiting to be ecstatically smacked past a flying goalkeepers outstretched arms, that universal orb, the soccer ball.

I am six years old and walking with my father to the flower gardens at the summit of Gladstone Park. I like the dwarf hedges there, which make me feel tall, and the stone sundial. It takes us a long time to reach the gardens because my father stops frequently to rest his weary heart. It is Saturday afternoon. When we arrive and enter through the trellised gate heavy with ivy, we see Rabbi Rabinowitz and his son David sitting on a bench next to a freshly trimmed yew tree. The rabbi and my father are still in the same dark suits they have worn to synagogue that morning. I have a tennis ball in my pocket. I have kicked it through the park, running ahead of my father to retrieve and kick it again. David gets up and stands about ten feet away from me, facing me without speaking. I put the ball on the ground and side-foot it toward him. Frozen rigid, he makes no move. He isnt allowed to play with a ball on the Sabbath. The ball rolls into an undergrowth beneath the yew tree. I search but I cant find it. Im not sure if my father is embarrassed that he has allowed me to come into the park with a ball, or if it is all right.