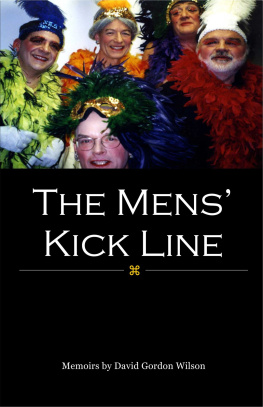

THE MENS' KICK LINE

Memoirs by David Gordon Wilson

Caption, cover photo of book: My friends in the photo have given me their permissions to use the photo in this way, but I will not name them here. They deserve and have my great appreciation. I am the beauty at the center of the back row. We are from the stage crew of the Winton Club show to support Winchester hospital.

FOREWORD

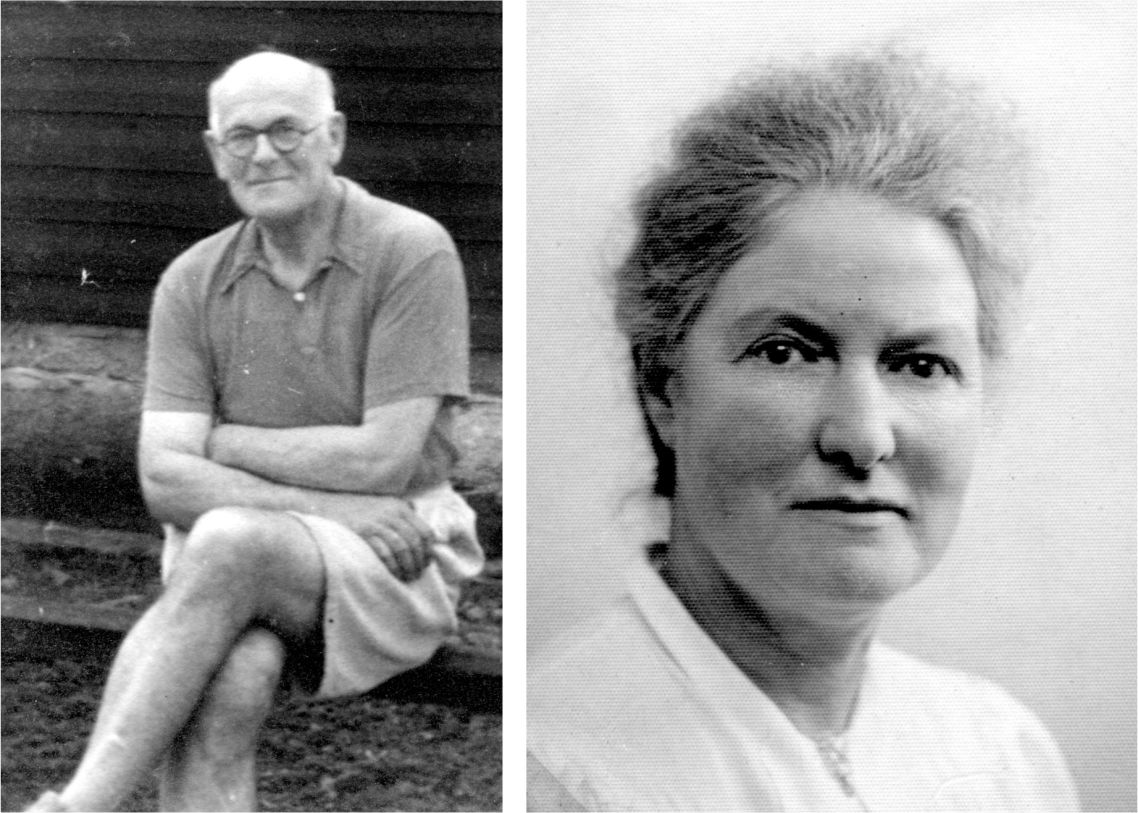

William (Willie) Wilson, my father, in around 1940 and My mother, Florence Ida (Boulton) Wilson at about the same time

This, as with the memoirs of many others, was started because I didnt heed the advice of my paternal grandfather, William Wilson. He used to tell us wonderful yarns about seafarers and adventurers, and sometimes he would write them out in a beautiful copperplate script. And just occasionally he would say something about his boyhood in Britain and Malta and his life in New Zealand. He seemed to be a permanent fixture, but he died in 1946 at 94, leaving very little tangible information. I was still young, and didnt feel the loss until later. My father, also named William Wilson, died not too many years afterward (1952), leaving much more in the way of papers, books and photographs but very little personal information that could give the reasons for some of the big choices he made. I began to realize that we were losing our familys heritage, and every time I visited my mother I would ask her if she would spend an hour with me telling me about her childhood. And she would say Not today, my boy, Im tired. Next time! She died before next time materialized. I decided that I was going to be more forthcoming. I soon found that my family did not seem to be any more interested in my life than I was in my parents and grandparents lives, and thought All right then! Ill go public with it! The result is before you.

George, David, Marjorie and Tom in about 1929

David with Grandpa Wilson, 1941 approx.

The title of this book is, of course, a metaphor. Our town, Winchester, Massachusetts, has a womens auxiliary that raises money for Winchester Hospital, principally by an annual musical extravaganza called the Winton Club Cabaret in the town hall. The husbands of the women are the stage crew, helping to make scenery. One year the women decided that the men should be on stage in drag, and we had a kick line. Some of my colleagues were gracious enough to give me permission to include them along with me in the cover photo. Thanks, chaps!

The title also covers some campaigns in which I have become involved, almost all involving other men. Throughout my college days I wanted to be in industry, but my professor for my PhD research told me quite firmly that I was destined to be a professor in a university. I denied this vigorously. Moreover my friends told me that conflicts are more likely to occur in academia than elsewhere. However, one of my first battles was in fact in industry in Britain. I was asked by my boss to falsify some test results so that a large turbine generator would be accepted for export to Brisbane, Australia. I refused. Then my bosss boss, a famous turbine engineer whom I greatly respected, sent for me and ordered me to do the deed. Again I refused. At that point I was required to see the technical director of the whole enterprise, who was among other qualifications a Methodist minister at weekends. After he preached fire and brimstone at me and I consequently did the awful deed, I wandered in the wilderness of the plant, and eventually decided to blow the whistle to the Brisbane inspector. What happened then was a significant part of the reason that I left Britain for the US, twice. (Read all about it in chapter 5.)

The second time that I went to the US (1961) I joined a small consulting-engineering company (NREC) in Cambridge MA; I had previously been teaching at a university in Nigeria from 1958-60. After a few enjoyable years at NREC I was offered an associate professorship at MIT. I thought that I had gone to heaven. However, I was brought sharply to earth. MIT is an amazing place, full of brilliant people working very hard to improve the world (and, frequently, their place in it). It also had a few people with the capacity to lie repeatedly to advance their own careers or to harm those of others. Moreover, they seemed to be untouchable. I found myself and my uncertain career at the mercy of some of these blackguards. I also seemed to become a magnet for people who had become victims of similar people and who wanted me to help them. Chapters 11 and 14 are devoted to serious conflicts at MIT.

Along the way I've had a frightening brush with the Mafia (chapter 11); a very stimulating encounter with some other merchants of death, the US tobacco industry (chapter 13); a doomed-to-failure battle with the Pentagon; a moralistic dispute with the U.S. Department of Energy; an engagement or two with Metro-Vickers (chapter 4) and with General Electric; an out-of-balance contest with the Great and General Court, Massachusetts (chapter 12); a fascinating encounter with a massive Manchester (UK) landlady (chapter 4); the inevitable tussle with my father (chapter 1); and a strike against a class-ridden Bible group (also in chapter 1), among others. As part of an attempt to help a tyrannized junior MIT colleague, I was threatened with four months imprisonment by Judge Hiller Zobel in Middlesex Superior Court (Massachusetts), possibly my proudest moment (chapter 14).

Being president of the US gives one a "bully pulpit" from which one can pronounce on any aspect of life. A professor at MIT also has a pretty large bully pulpit. I indulge here in comments on various aspects of life, including engineering, that I wish that I had known from the start of my adult life. You will recognize early on that professors at MIT or elsewhere should not necessarily be trusted on any topic, but you have this book in your hands, and you can pick and choose among the wisdoms and idiocies being preached.

Some notes about how this saga is organized

After I decided for reasons stated above to produce some sort of autobiography, I began writing about what, for me, were the most exciting moments. Many of these times were also turning points: as a result of those events my life could have gone one way or another. It seemed to be a good idea to grab the readers attention from the start with a description of some dramatic situation. But as I began to amass more and more turning-point events I found that I had to spend more and more time explaining the relationships among them. What seemed clean became more messy.

It was a good point to start finding out what others had done. I have always liked reading biographies and autobiographies, but previously I had read them for education and pleasure. Now I read and looked for models and guidance. I read Peggy Noonans, David Brinkleys, and Katherine Grahams with great enjoyment. In general they told the stories of their lives chronologically. The clear message was that I should do the same.

However, there was a major difference between their autobiographies and anything that I might write. They were famous. They interacted with national and international leaders. They took part in significant occasions about which we all want to know the inside stories. It was fascinating to learn about their rise to positions of prominence from, in two cases, humble beginnings. It was gripping to read about the obstacles put in the way of women and of someone who was part-Jewish. Readers would have none of this fascination with my story: Im not famous, and I havent taken part in major national events in any way that would make readers yearn for the inside angles. Im a white male of fairly humble origin and on my way to a fairly humble ending (unless, of course, this book lifts me to fame).

Next page