To my wife

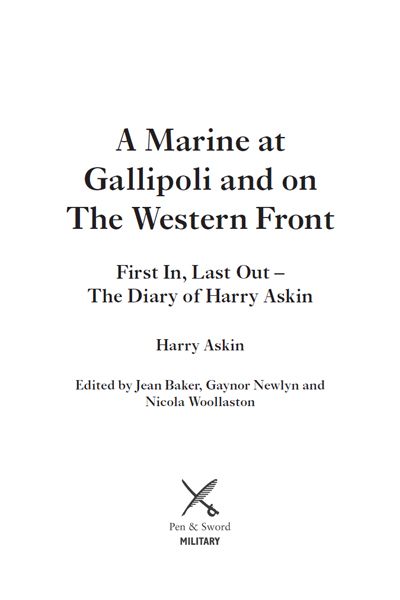

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Estate of Harry Askin 2015

ISBN 978 1 47382 784 4

The right of the estate of Harry Askin to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd,

Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

I have tried in the following pages to give a true and unexaggerated account of my travels and of all that happened to me from leaving England, under orders with the MEF, to landing at Marseilles, where we were taken over by the BEF.

The first chapter of my book was actually written during the voyage, the rest I have taken from my memory, aided by my diaries, which I kept almost religiously, often entering notes under heavy fire but always sticking strictly to facts.

It is impossible to set down in writing just what those months on the Peninsula meant to me and to all the other fellows there and I have been content to write down the chief items of interest.

I may as well state here that I enlisted in the Royal Marines on 22 September 1914 at Nottingham and was sent from there to Portsmouth.

The interval between joining and leaving England was spent, on the whole, pleasantly, training at Portsmouth, Fareham, a three-day route march in glorious weather through the New Forest to Lyndhurst and Ringwood, finishing up at our final training place at Okeford Fitzpaine, a lovely little place in Dorset.

Blandford, about six miles away, was the training centre for the Royal Naval Division.

Here we got fit for the big move.

Harry Askin

Chapter One

27 February 1915 The Voyage

P ortsmouth Battalion Royal Marines received orders to move from Okeford Fitzpaine. We had quite a busy time returning gear, bedding, ammunition and office material. I just had time to write two short letters and a few postcards home to let them know we were off at last. All our chaps were disappointed at having no leave, as some of the Naval battalions had been granted a few days at home and we quite expected the same before we left England.

We were all feeling excited and eager to be off, although we had no idea where we were bound. Several guesses were made as to our destination: France, Malta, Egypt, Serbia, German East and West Africa. It was certain to be somewhere hot as we had been served out with huge sun helmets. Marched down to Shillingstone station about 5.00pm, well stocked with food and drink and most of us with a few luxuries that the good people of Okeford had given us. All the village turned out to see us off and most went with us to the station.

It was 6.30pm when we got away, as most of the RN Division were in training there. Pushed right in a carriage, which was quite enough with full marching order. We managed to keep fairly lively on the journey, having plenty to eat and some jolly good cider to drink. We had a lively chap in our carriage who kept things going. Dolly Gray was his name. All Grays in the marines are Dolly, the same as all Martins are Pincher and all Bells are Daisy. This Dolly was a bird. He must have been, and so must all old soldiers who serve about twenty-one years in a regiment and finish up with the same rank that they started with. He had been with the division in the show at Antwerp and was the sole means whereby our battalion got back to safety with so few taken prisoner, so he told us. However, he could be good company and we passed the time fine. Went past Bath and finished up on the docks at Avonmouth about 11.30pm, scrambled out of the train It was blowing strong but the ship was steady and I thought then that I could stand sea life forever.

Things were pretty rough in the morning and I could hear the sea coming over on to the well deck, and when I got up I knew that the ship was pitching and rolling. Went up on deck and it was grand to watch the great waves as they dashed over the bows of the ship. It was jolly wet though and presently I began to feel a queer sensation inside me and also observed several chaps leaning over the side and others making a dash for it. I was soon over, and by the time breakfast was piped 80 per cent of the battalion were helpless. Men were just lying about anywhere, not caring whether the place under them was wet or dry. Mess orderlies, told off for the day, tried hard to carry out their duties but, when it came to manipulating dishes of sloppy porridge along the greasy shifting decks, they all seemed to fail. Porridge was everywhere and on nearly everyone. Id nothing to eat that day and did nothing but lie about on deck. Felt better about 5.00pm and the sea had gone down a bit to help matters. I didnt feel well enough to fit my hammock up, so slept on the mess deck. Conditions were much better in the morning, warm and bright, and everybody woke up with enormous appetites. It was bloater morning though, so I didnt get much chance to satisfy mine. I never was very partial to fish which had millions of bones in it. The only other course for breakfast was bread, rank margarine and very indifferent jam with some terrible tea out of a tin mug to wash it all down.

The meals were rotten. It was a bloater one morning and porridge made without sugar or milk the next. Try salt with it, one old soldier said one morning. I did and nearly had a repetition of the first day. For dinner we had either stewed meat or a roast with small bad potatoes. Twice a week we had duff. The best meal was Saturdays dinner when we had corned beef, pickles and potatoes. The company was vaccinated on 3 March, but I managed to wriggle out of it. I had gone back to my old job of company clerk and had a pretty soft time with a nice deck cabin as an office.

We arrived at Gibraltar early on 5 March and everybody rushed up on deck to get a view. However, it was misty and all we could see was the dim outline of the big rock. Had it fresh all that day, but the next was fine and warm. We steamed close to the north coast of Africa that day and the next, and saw some of the most gorgeous scenery. We passed close to several towns, Algiers and Tunis being the largest. The coast appeared rocky and, far inland, we could see huge snowcapped mountains. The troops were having a tottering time on board, first drawing rifles from below, then returning them, drawing helmets and packs and doubling round the ship scores of times.

Next page

![J K Rowling - Harry Potter [Complete Collection]](/uploads/posts/book/117015/thumbs/j-k-rowling-harry-potter-complete-collection.jpg)