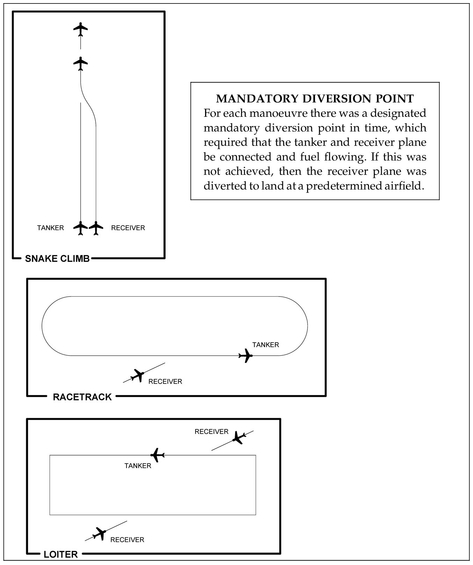

APPENDIX 4

RAF Air to Air Refuelling Procedure Diagrams

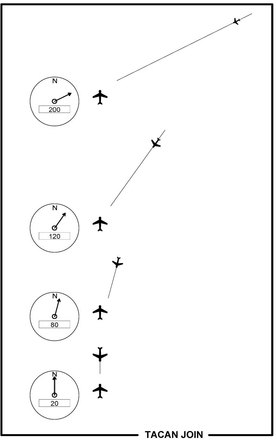

Receiver aircraft at FL280, 200 miles to run, approximately 45 to starboard. Tanker at FL300.

Tanker RT

Tanker to receiver. Confirm FL280. Channel selection 40 air to air. Make heading 220.

Receiver aircraft maintains FL280, 120 miles to run, approximately 35 to starboard. Tanker maintains FL300.

Tanker RT

Tanker to receiver make heading 200.

Receiver aircraft maintains FL280, 80 miles to run, approximately 15 to starboard. Tanker maintains FL300.

Tanker RT

Tanker to receiver make heading 185.

Receiver aircraft starts to climb to FL300, 20 miles to run. Both aircraft on reciprocal headings. Tanker maintains FL300.

Tanker RT

Tanker to receiver make heading 180.

The standard procedures used by the RAF to ensure tanker and receiver planes met up according to schedule.

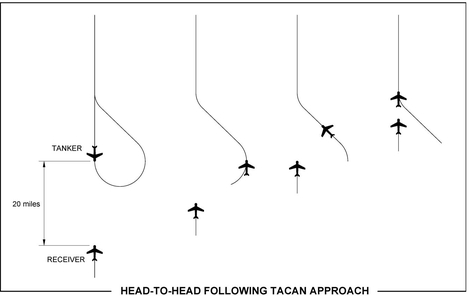

HEAD-TO-HEAD INITIAL TACAN APPROACH

For the head-to-head procedure the TACAN is used to position the fast closing aircraft (1,000 mph closing speed).

The Nav/Plotters TACAN instrument reads off the distance between the tanker and the receiver aircraft and indicates an angular deflection from the tanker nose. He then talks the receiver plane into the twenty mile position with instructions to both pilots.

The procedural join as shown in the diagram then follows, starting with the tanker commencing a broad turn to take it back in a reciprocal heading. This initial part of the turn presents the incoming receiver plane with a large side profile of the tanker for identification and location purposes for the visual join.

CHAPTER 1

Early Days

T he red brick suburbia of the Golds family home in Romford could not have been further removed from the country cottage of his grandmother where the young Tony Golds first childhood memories started to form. Romford was a fairly typical smog-ridden 1930s London suburb and the Golds family was one of hundreds of thousands of hard working East London families who listened with increasing trepidation to the news of German rearmament, and the increasingly strident speeches for expansion and war from its leader, Adolf Hitler. Perhaps that is a slight exaggeration, in that it grabbed the attention of Frederick and Violet Golds, but had little effect on their three children, Jean, the eldest, Tony aged four and Doreen who was still a toddler. To them, life was mainly about friends, playing games and London Road School (Crowlands).

Number Two Stanford Close, was a typical mid-thirties, brick-built suburban family home tucked away at the end of a residential cul-de sac, not far from Romford town centre, its shops and the railway station. Like most houses of the time, it was a basic three-bedroom dwelling heated by coal fires and without the benefit of a separate bathroom, a hot-water system, or inside toilet.

The children and family washing shared the facilities of the kitchen sink. The children used it on a daily basis with the added supplement of a weekly (Friday) bath, and the family clothes wash took it over on the Monday of each week. The water for all three activities was boiled up in a copper in the middle of the kitchen (until a boiler was installed over the sink by the landlord some years later). Violet Golds scrubbed the washing in the sink, on a ribbed scrubbing board. The table was then turned into a temporary base for the mangle, which she used for squeezing as much of the excess water from the washing as possible, before it was hung out in the garden on a clothesline to dry. Over the winter months an airer went up in the kitchen, as outside drying became a less than successful operation due to lack of sun and the effects of the dirt in the smog that hung over the whole of London and its suburbs for days on end.

The smog was a heavy sooty fog produced by all the coal fires that heated Londons homes and powered its industry. This smog would produce the first childhood memories for Tony. At the age of three the smog and his fathers lifelong enjoyment of some forty Players cigarettes a day, conspired to give Tony a severe dose of bronchitis and a brief spell in the childrens ward of the local hospital.

I can recall crying in the hospital, although at the time of course I had no idea of what was wrong with me. I recovered from this illness fairly rapidly, fortunately without any long-lasting effects. My life then followed the regular pattern for children in my area as I enrolled and began to attend London Road Primary School where my elder sister was already a pupil.

To her dismay, being several years older than me, she was compelled to take me to and from school on a daily basis. For this reason and perhaps others, I was not her favourite sibling and she was not afraid to let me know it. However, once at school, I did at least have a good bunch of friends to play with.

As time went on and the threat of war became a reality, we would often stand in the road and watch in awe as the planes in the sky wheeled and manoeuvred as the dogfights of the Battle of Britain took place over our heads. The noise of the German bombers passing overhead and the frequency of the heavy explosions of the nearby bomb blasts at night were as distressing to a bunch of five to six year olds as the aerial ballet above us during the day, was enjoyable.

Nonetheless, we were all totally convinced the whole show was put on for our very own personal entertainment.

Between the wars Frederick Golds had been brought up by his mother in the small, sleepy Sussex village of Horsham. Now, as the bombing intensified, he and Violet began to feel that it was all getting a bit too close for comfort, and as many houses in their area had been either destroyed or badly damaged, it was time to move the children away from the danger. Peaceful, rural Horsham seemed ideal. Thus in early 1940, Jean, Tony and Doreen were told by their father that they were going for a long holiday with Grandma Pyzer. Like so many other London children at that time, they were to become evacuees.