First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley,

South Yorkshire.

S70 2AS

Copyright Martin W. Bowman 2012

ISBN 978-1-84884-755-2

eISBN 978-1-78303-909-8

The right of Martin W. Bowman to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset by Mac Style, Beverley, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword

Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport,

Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press,

Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact:

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England.

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

This book is dedicated to the firemen and firewomen and the other services E. C. LeGrice FRPS, Clifford Temple, George Swain and the other brave and resourceful war photographers who risked their lives during the bombing raids on Norwich in WW2 to photograph the destruction at close quarters.

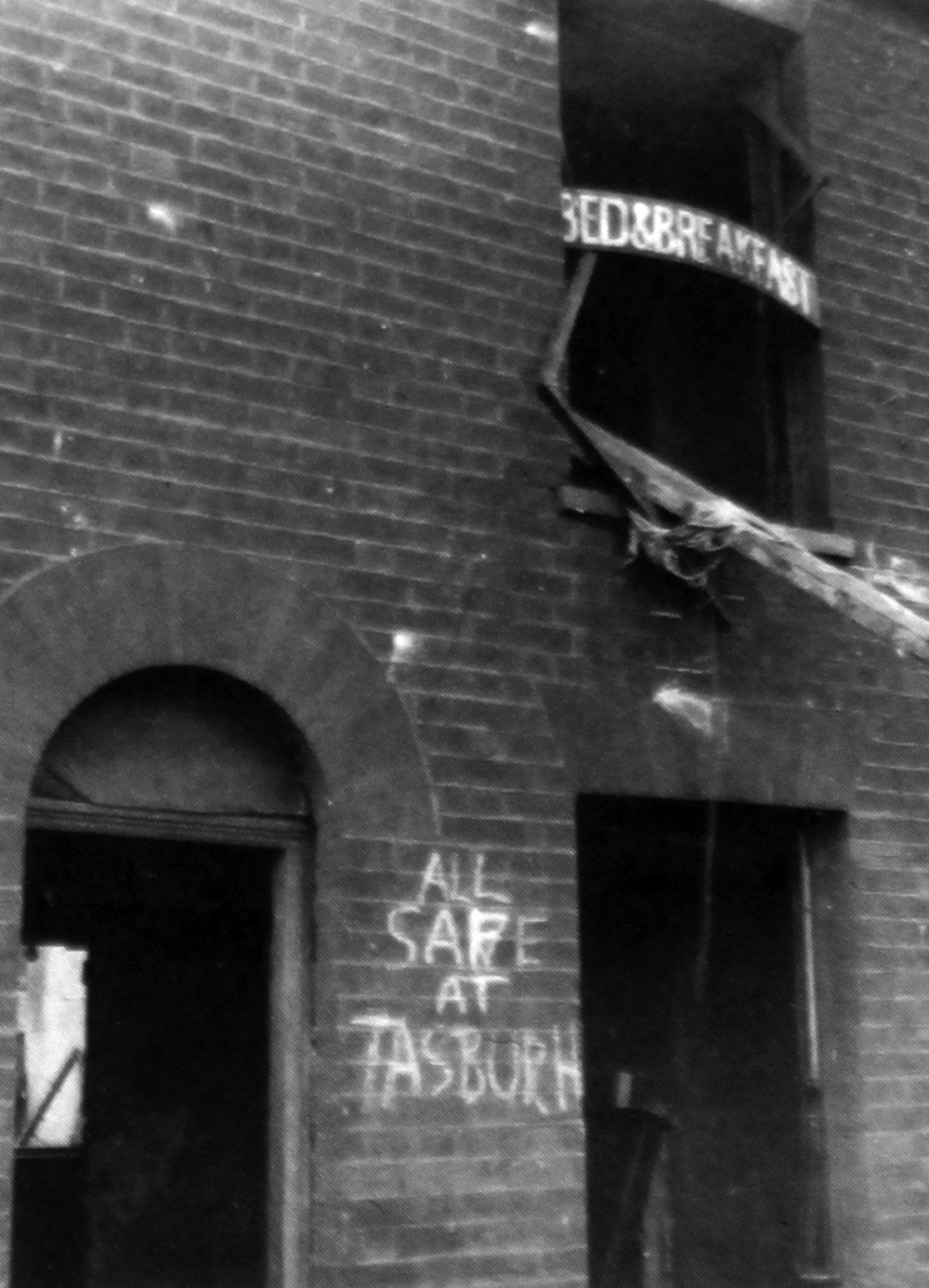

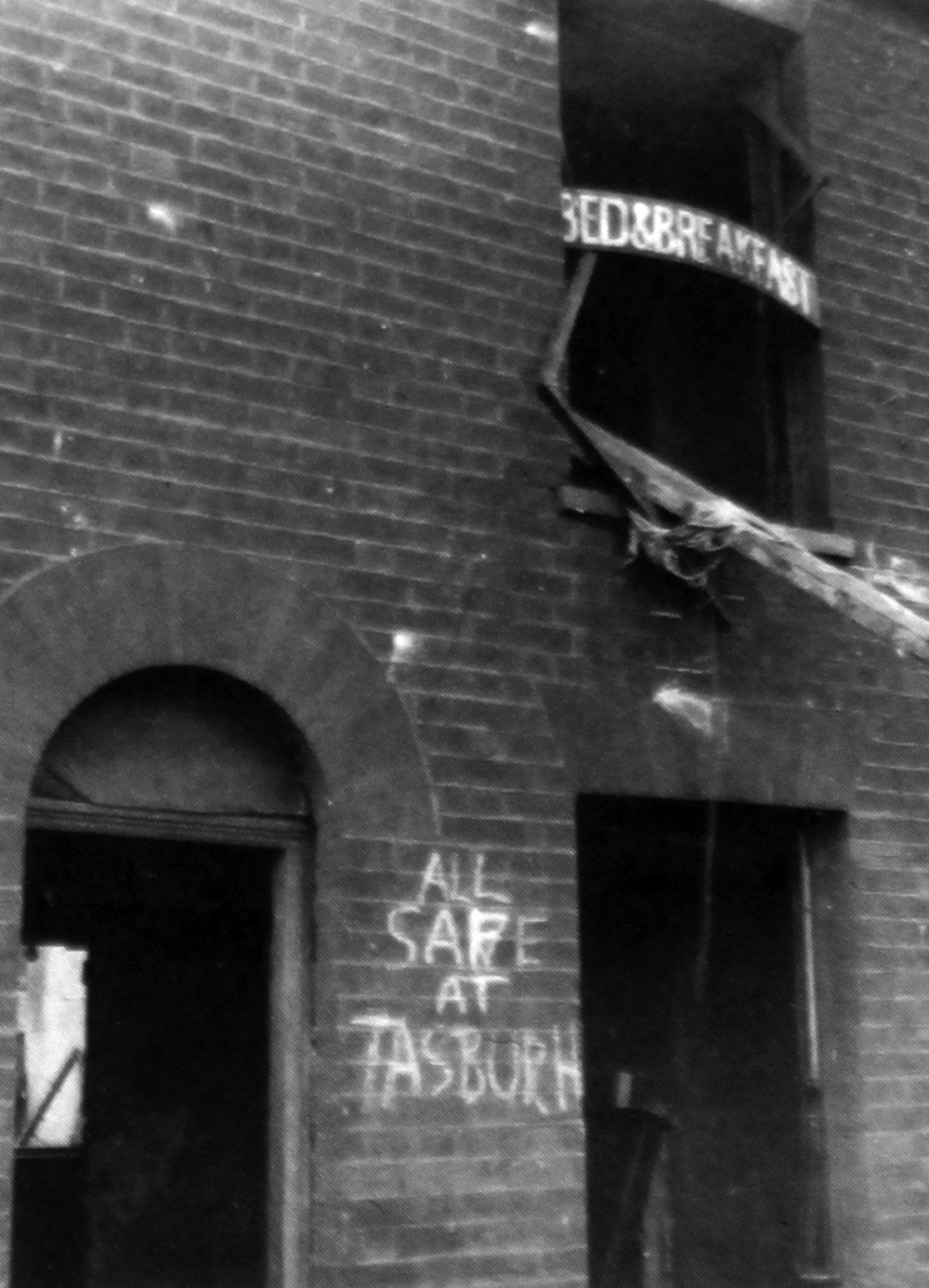

House on Exeter Street off Dereham Road with letters proclaiming that the family were all safe at Tasburgh. Someone has scrawled the ironic message Bed & Breakfast over the top right hand window.

Acknowledgements

I am especially grateful to Bob Collis who graciously made available his account of the Baedeker raids on Norwich and which is referred to throughout. I am also indebted to Norman Bacon, Mike Bailey; Nigel McTeer; Jack Richardson; Norwich 2nd Air Division Memorial Library; Norwich Castle Museum; Sallie Watson; and Tony Hatch.

Norwich City Hall Isnt Paid for Yet but never Mind, the Luftwaffe will soon put paid to it

On Tuesday, 9 July 1940, a warm afternoon, the dull throb of aircraft engines could be heard from high in the sky near Norwich. At Mousehold aerodrome on the outskirts of the city no air-raid siren was sounded. At Barnards Iron Works, a collection of First World War hangars and outbuildings, there was no cause for alarm. Although the Battle of Britain was about to start the cathedral city was not yet in the front line. When an air raid warning was sounded, a young teenager, Derek Patfield, took his place as one of the pairs of spotters in the watch tower erected on the top of the Enquiry Office, watching for enemy attack. To relieve the boredom he often trained his pair of powerful binoculars on the young female employees walking between the workshops and offices. If he saw approaching enemy aircraft, or thought they identified one as enemy Derek pressed the alarm siren, which sounded all over the works resulting in the employees dashing to the air-raid shelters. When the young spotters got fed up with the lack of aircraft activity during their two-hour shift, they would sound the siren, just for the hell of it, to see the panic it caused! False alarms were explained away as incorrect identification.

At five oclock when the two aircraft approached from the northeast, flying at about 600 feet, they made out the black markings in the shape of crosses on the wings they flung themselves to the ground. They were Dornier Do 17s! Barnards was hit by twelve 50kg high-explosive bombs. Three bombs, which failed to explode, were also dropped. The raid was all over in six long seconds. Two men who were working by the loading dock were killed and another threw himself to the ground 20 yards from where a bomb exploded but his only injury was a damaged toe, which later had to be amputated. One worker had a most remarkable escape when a bullet or bomb splinter went through his trouser-leg while others pierced the walls on either side of him. One of the aircraft was seen to bank away towards the centre of the city.

At the famous Colmans Mustard Works at Carrow, workers coming off shift poured through the main gates jostling, laughing and bicycle-bells ringing. As the Dorniers suddenly appeared overhead many of the women were pushing their bicycles up Carrow Hill. The Dorniers banked a little and dived and the sound of a whistling bomb rent the air. The older men remembering the sound of falling bombs from the First World War threw themselves to the ground, at the same time shouting to the women, Down! The women and girls did not immediately abandon their bicycles and they did not throw themselves to the ground. A bomb crashed through trees at the top of Carrow Hill near the Black Tower and exploded at ground level. The resulting blast and flying splinters of stones, earth and glass killed Bessie Upton (36) and Maud Balaam (40) instantly. Gladys Sampson (18) and Bertha Playford (19) died shortly after being admitted to the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital. Maud Burrell (37) finally succumbed to her injuries on 12 July. A further four bombs hit the Boulton & Paul works in Riverside killing seven men and three men died later of their injuries. Four men were killed when one of four bombs dropped on the LNER locomotive sheds and goods yard at Thorpe Station exploded. Three others died later of their injuries.

On 2 December 1940 a bomb fell in the grounds of Carrow Abbey and another on Bracondale which killed Mr. Arthur John Pennymore (55), a member of the counting house staff at Colmans who was on duty as a special constable.

Norwich, in common with most English cities, suffered enemy attack from the air and, during a period of almost three and a half years bombs were dropped in every part. To most young people recalled J. Fincham the year 1940 meant nothing, but to me it was my first taste of the bomb dropping, which was to take place in Norwich in the next three years. I was at Boulton & Paul in the box shop with Charlie Banfield as my foreman. On Thursday, 1 August I was working a bench drill next to a young lad, Alfred Swan, when suddenly the hooter went one, two, three, seconds: Duck Swanny! I shouted and under the bench we dived. Perhaps another two seconds then the bomb hit the canteen killing nine workers with injuries to about 20 more. We were about 50 feet away with a wall in between and were covered with anything that happened to be blown our way. Thank God, on picking ourselves up we found we did not have a mark on us. But by this time the place was on fire which resulted in its complete destruction.

Mrs. L. F. Kellow, who was living in Mill Hill Road particularly, recalls an incendiary raid in 1941: Our garden adjoined the gardens of houses in Park Lane. Two of these were hit by a group of incendiary bombs during the night and despite every effort were soon burning furiously. In an upstairs bedroom facing our home hung a large picture of Queen Victoria portrayed in old age. At first we could see her through the window amid the flames brilliant light stern, uncompromising, resolute. The roof fell in, the window and all came down. Still she remained on the inner wall surveying the devastation. Finally, after what seemed an age, she fell and was consumed by the flames. I was young then and that picture and situation made a deep impression on me as recording the spirit of those times.

Next page