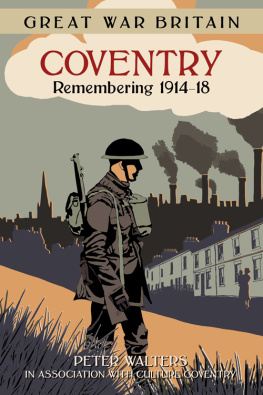

The Blitzed City

Contents

List of Illustrations

Few stories stir the heart like those of survival in the face of adversity. Seventy-five years ago, Coventry and its people endured a punishing air attack that left hundreds of people dead. Thousands more thought they were going to die that night as a blizzard of bombs fell indiscriminately, hitting homes and industry. This is a story of ordinary people in extraordinary times and it is told by the people who were there. These are the illuminating accounts of Dennis Adler, Eileen Bees, Janice Chapman, Len and Cecilia Dacombe, Betty Daniel, Marjorie Edge, Alan Hartley, Mary Heath, Mary Latham, Eric Lloyd, John Sargent and Christina and Len Stephenson. I am indebted to them for allowing me to raid their memory banks so extensively. Other accounts have been taken from numerous archives to give as broad a picture as possible of this shocking night and its grim consequences. Those that provided particular assistance were at the Imperial War Museums, the Herbert Gallery and the National Archives.

For stretcher-bearer Dennis Adler, it was a sight that would remain etched in his memory forever. Aged fifteen, he was already an old hand at working through the night as a volunteer cadet for the St John Ambulance Brigade. He had become accustomed to seeing crushed limbs and bloodied faces, and he could even carry a corpse without flinching. But the waiting room in front of him was like nothing he had witnessed before.

At first glance, it looked like a scene from a military hospital. As bombs plunged through buildings and flames reached the height of rooftops outside, the casualties who poured through the doors looked something like battlefield cannon fodder. Yet, this was not the aftermath of a campaign, nor was it combatants who were suffering such grievous injuries. It was the night of the Coventry Blitz and these victims were civilians who had become the collateral damage of a new phase of a terrifying, modern military struggle.

By day, Dennis Adler was employed helping a milkman to deliver dairy items by lorry to the nearby town of Kenilworth for the Co-op. He had already notched up jobs as an office boy and a factory hand, but it was outdoor employment that he relished and he had more in his weekly pay packet than the ten shillings a week he had previously earned.

He spent his afternoons asleep, and at night, he devoted hours to the Gulson Road Hospital in Coventry. It was a small municipal hospital with a single operating theatre the size of an average sitting room. Even in those times of crisis, there were no more than four doctors on duty.

Initially, he nearly missed this shift at the hospital. Fearful of the raids early intensity, his father Harry had almost stopped him from going. As the family made its way to a shelter, Dennis had finally persuaded his father that it was appropriate for him to peel off and report for duty. Dennis did not realise, as he spoke kindly to one patient here and gave a drink to another there, that he had already delivered his last pint of milk. It would be weeks before Dennis left the hospital again.

More casualties arrived who needed his attention. This time, it was a mother with a baby in her arms. Both looked like they were sleeping serenely, but to his horror, Dennis suddenly realised that they were dead. A doctor explained that the invisible force of a bomb blast had killed them. They had died from internal injuries, although both were quite unmarked.

It was not only ambulances that brought patients to the hospital. Every kind of vehicle was used to ferry them in and more hobbled there on foot. Soon, there was no electricity to light the hospital, or water to mop up wounds. It became harder to administer even basic treatment to the streams of people in need.

Later, Dennis recognised some of the firemen being brought in with injuries. They had been stationed opposite his school and used to wave at pupils such as him. All of them died as the hospital struggled to cope, with people perishing from shock, for want of warmth, or for loss of blood.

Alarm at the mounting death toll made him pause for a moment. Then Dennis pulled himself together and helped to move bodies away from the main waiting area to make room for more patients. That night he along with numerous others worked tirelessly for the very survival of the city and its people.

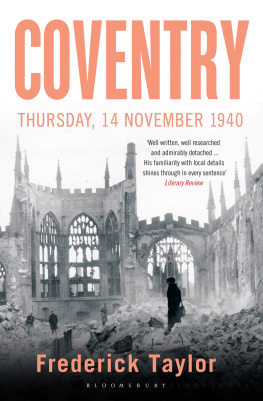

On a frosty Thursday night in the winter of 1940, Coventry was laid waste by an aerial bombardment. Today, terror among civilians sparked by a thunderous rain of bombs from high-flying aircraft is a harsh reality that happens on an alarmingly regular basis. Back then, the grim art of the Blitz was in its infancy. Until that fateful raid aeroplanes tended to travel in twos or tens rather than in hundreds. Bombs were getting bigger, but they were still comparatively modest in size. The chances of hitting a target with one that had been launched from an aeroplane at high altitude were slim, as accurate navigation was too often a matter of luck for a pilot and his crew. Conversely, any defence against enemy fliers was still largely ineffectual.

The devastation of Coventry acclaimed worldwide as a medieval gem marked the moment that the bomber came of age. Before that moment on 14 November, both sides clung precariously to the moral high ground, claiming their targets were military ones. When the truth of the matter was consistently proved that bombs fell indiscriminately on the civilian population as well as the munitions factories they worked in an idea formed in the minds of those planning the attacks: why not bomb the people who were making armaments as well as the armaments themselves, to crush their spirits, create pandemonium and thus bring a speedy end to the conflict?

Although it was not the first city to be bombarded and it certainly would not be the last the attack on Coventry changed the tenor of aerial warfare. London had been Blitzed, but the city was too sprawling for the terror to be a game changer. Coventry was smaller and more compact. If the terrible effects of a concentrated attack could be maximised anywhere, it was there and German air chiefs were keen to experiment with this new tactic.

The Luftwaffe not only used incendiaries to best effect but also its navigational technology, which, although far from foolproof, was way ahead of that of the British. It had the means to get pilots to the correct location and help them aim their bombs. Consequently, the facts and figures of the ferocious dusk-to-dawn raid are brutal.

Between 30,000 and 40,000 incendiaries fell on both military and civilian targets. Most were standard blaze-setters, but about a fifth had a delaying device that then caused an explosion in the face of fire fighters, inflicting burns and blindness. More than 503 tons of high explosives tumbled through the night sky, in an estimated 16,000 bombs some of which weighed as much as 1,102lb. In addition, fifty parachute mines, each weighing in at 2,205lb and containing 1,543lb of high explosives, were dropped.

It is thought that 568 people were killed out of a population of 238,000, with a further 863 seriously injured. The circumstances of their demise are shocking, with people burned, crushed, shocked or frightened to death. The true figures may never be known and the city is still dogged by rumours that the death toll was much higher.

Yet the story of the attack on the city is not just about a switch of strategies by German High Command and those who perished in terror that night because of it. It is the tales of those who survived, drawing on inner resourcefulness and iron will, that make the event so memorable. Not everyone was a hero, although there were many who emerged as such from the fire and the chaos. Nor was there a higher-than-average proportion of cowardice. Most people fell between the two extremes, ordinary people coping as best they could in appalling conditions. And what the city had in abundance was people.