In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

For the sake of privacy, I have changed all first and last namesincluding my own and those of my family membersexcept for Dr. Cory Shulmans. For the sake of clarity, I have left out certain characters. The stories passed on by aunts, uncles, great-aunts, and great-unclesguardians and messengers of the family historyare all told in the book by one beloved aunt. It is the same with the children: Blimi, my best friend, is a composite of several young friends, all of whom knew or repeated rumors and myths that surrounded the strange mystery that was my brother.

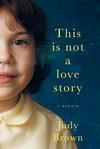

This book reflects the memories of a young girl, written over two decades later. It is an attempt to re-create the world of a child caught in the family maelstrom of a brother afflicted with a horrific disorder no one at the time could understand. The memories belong to me only. It is a narrow perspective but an important one, and written with the full knowledge of its power and its faults. My brothers story unfolded over the course of years. It involves many people and perspectives. More than one person could write his story.

This telling is mine.

Once, when I was in third grade, my teacher said that it was forbidden to fall in love. It was God who decided who would marry whom, and only the rebbe knows these secrets.

You see, up above the clouds, by the royal throne, God and his angels are gathered. It is there, forty days before each person is born, that a heavenly voice calls out in the skies, proclaiming, The daughter of this man and this woman will marry the son of that man and that woman.

Or something like that. It says so in the Talmud.

My teacher also told us about that time long ago when a Roman princess asked a great rebbe, What has your God been doing ever since he finished creating earth? And he answered, Matchmaking. The Roman princess laughed. She said, I can do that too, and ordered a thousand of her female slaves to be paired up with a thousand of her male slaves that very night. But the next morning, they came to her, all two thousand, with scratches and wounds, crying, I dont want to be with him, I wanted to marry someone else There was chaos in the court.

The Roman princess immediately called the great rebbe. She said, Rebbe, every word in your Torah is great. Only your God is true.

So this book about my familys curse is not a love story. Because my mother and father never fell in love. That would have been a terrible sin, a gentile kind of nonsense, and my parents were pious people. It was my brother who was crazy, crazy as a bat, and because of him we were cursed. Thats why people told lies about my family, things about love and suchstories that could never be. It says so in the Talmud: There is no such thing as love.

September 1988

When I was in third grade, I made a deal with God.

I would fast for forty days and nights, and in return Hed make for me a miracle. Fasting forty days and nights was an ancient custom, a powerful way to get Gods attention. All the holy saints of once upon a time did this. They had to when they realized just how stubborn God was, and that there were problems for which prayers were not enough. God wanted suffering.

I needed this ancient omen to work so that Hashem, our one true God, would get me new heart-shaped earrings. I figured if the saints could get Hashem to listen when they asked for rain after a long drought, or for an end to a terrible plague, it would certainly work for me. Earrings were a simple miracle.

The earrings I wanted were pretty, ruby red, with a perfect glow, lying in the window of Golds jewelry store in Borough Park. I had first seen them two weeks earlier when I went shopping with my mother for a school sweater and school panty hose. I had prayed and prayed for them ever since, but nothing had happened. Id thrown in extra psalms before bed, yet from Heaven there was only silence.

Then my third grade teacher, Mrs. Friedman, told us the story about the saints and their forty-day fasts during times of drought. She described how on the fortieth day, at the stroke of dawn, as the red streaks of sun rose above the earth and the gaunt, starving face of the tzaddik, it began to rain. Nay, pour. And the people of Israel were saved.

That afternoon, I sat in the big, wooden blanket box attached to the head of my bed and struck a deal with God. I would fast for forty days and nights, and He would get me the earrings.

After a thorough talk, it was agreed. I climbed out of the box.

I began my fast the next morning. I got out of bed, into my school uniform, walked to the kitchen, and pulled the cornflakes from the shelf in the pantry. Then I remembered. I could not eat. I was fasting.

I put the cereal back and went to my room. I sat on my bed and thought. Mostly, I thought of the cereal. I was hungry. I wanted to eat now. I had always known that fasting meant not eating, but I had never connected it with hunger. Somehow the saints just did it. Somehow my mother did not have breakfast, lunch, or supper on Yom Kippur while I ate my snack in the shul yard. But real fastingthis was hard. My stomach was empty, my mouth watered, and my entire being wanted cereal, any cereal.

At school that day, my stomach growled loudly. By recess, I could barely hear my own thoughtsand this was only the first of forty days. Two minutes before the end of recess, I gave up. I could not do this any longer. I crammed an entire bag of pretzels in my mouth. The bell rang. I grabbed my lunch bag. I pushed my tuna sandwich into my mouth and chewed as I hurried back to my classroom. Then Mrs. Friedman walked in, and I sat at my desk, relieved. I now had a clearer focus. I could renegotiate with God.

Mrs. Friedman was teaching us the meaning of the morning prayers.

Girls, she said briskly, her long skirt brushing by my desk as she walked up and down the aisles, when we pray to Hashem, we are talking directly with a king, and not just any king, but the one and only king of the universe. The one and only king who can grant any wish in the world. When you stand in the royal court of a king, do you slouch? Do you yawn? Do you stuff banana into your mouth in the middle of the conversation?

Mrs. Friedman stood still. She towered over my best friend, Blimi Krieger, who slouched behind her desk in the first row. Blimi was holding a banana peel, the last of the fruit squashed furtively between the cover and the first page of her prayer book. She held the prayer book tightly against her chest, the banana squeezing slowly out the side. It landed with a splat on the floor.

And do you think, Mrs. Friedman asked, pointedly, that the king of the universe likes banana mush squished onto His heavenly prayers?

Blimi began to cry. Mrs. Friedman handed her paper towels to wipe the mess off her prayers. Then, once more, she walked up and down the aisles, nudging our pointer fingers onto the right line in the holy book.

All this was important, of course, even sacred, perhaps, but I had more urgent matters at hand. This fast wasnt working. I needed different conditions. I needed breakfast.