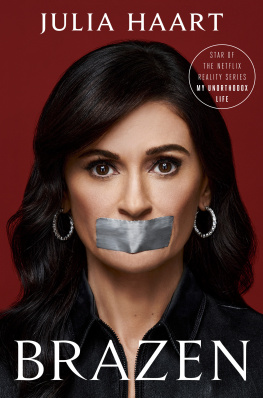

This memoir, which explores one narrative thread from a vibrant life, is based on my memories and my diaries and verified with others recollections. Names and identifying details have been altered. The character of Deena is an amalgam of a few of my siblings. Some events have been compressed or rearranged in time to more concisely convey my experience. As a girl, I was always told there was only one truthand it was never, ever mine. Now, as a woman, I know that there is no single truth. We can only convey the raw and awkward shape of reality as we each experience it.

That has been my labor here.

Copyright 2014 by Leah Vincent

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese / Doubleday, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House Companies.

www.nanatalese.com

DOUBLEDAY is a registered trademark of Random House LLC. Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Random House LLC.

Jacket design by Emily Mahon

Jacket photographs: skirt szefei/Shutterstock; legs eva serrabassa/Vetta/Getty Images

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Vincent, Leah.

Cut me loose : sin and salvation after my ultra-Orthodox girlhood / Leah Vincent. First edition.

pages cm

1. Vincent, Leah. 2. Jewish womenNew York (State)New YorkBiography. 3. Ultra-Orthodox JewsNew York (State)New YorkBiography. I. Title.

E184.37.V56A3 2014

305.8924082dc23

2013016764

ISBN 978-0-385-53809-1

eBook ISBN: 978-0-385-53810-7

v3.1

With gratitude to Phineas

and for Leahchke as promised

Contents

authors note

Orthodox Jews can be roughly divided into three groups: (1) the Hasidic, who are mystical and loyal to popelike rebbes; (2) the Modern Orthodox, semiassimilated into modern life; and (3) the Yeshivish, committed to the centrality of the yeshivasstudy halls where men ponder ancient legal texts. No strong statistics exist on these rapidly growing communities, but a very rough estimate might tally close to 1 million Hasidic Jews, about 1 million Modern Orthodox Jews, and 500,000 Yeshivish Jews, globally. The Hasidic and Yeshivish are the more powerful in the world at large, voting in blocs and lobbying hard to promote their values.

Growing up in a Yeshivish home, I was taught that Yeshivish Judaism was the authentic version of our religion, unchanged since Abraham. In fact, Yeshivish life was invented by my father and his peers. It was a fabricated mask superimposed over an existing religious community. It is not a natural incarnation of religious Judaism, a vibrant, diverse, and evolving faith.

My father and other American Jewish children of the 1950s were raised on stories of their European cousins being rounded up and murdered by the Nazis. For some, these cultural nightmares became motivation to prove their worth, fueling their ascent into the highest reaches of secular society. Others turned away from the opening vistas of the American dream to commit to a stiff reenactment of pre-Holocaust Eastern European life. In ever-distorted echoes, the shtetls provincial separation of the sexes was interpreted as a strict apartheid. The old respect for the indigent student became a worshipping of scholarly life. A love of tradition became an obsession with the law. This is the way it always was, insisted this new group, who would come to be called the ultra-Orthodox or Yeshivish. The remnants of the Orthodox Jewish community, reeling in the aftermath of the Holocaust, did not argue. And so the Yeshivish developed a story line that extended into the past, as if this way of life had always existed, and pushed forward into the future, as if it always must exist, unchanged.

If a Yeshivish Jew questions his or her path, it is more than a personal upheavala break with character threatens the whole tableau.

chapter one

MY FATHER, RABBI SHAUL KAPLAN , was a short, stiff-shouldered man with flat, sad eyes and a high forehead that faded into a bald pate. Like all Yeshivish men, he dressed in a dark suit, white shirt, and black fedora. When we picked through the laundry heap, looking for clean underwear, we would find his sleeveless undershirts and his worn boxers, translucent from too many washes.

There were eventually eleven of us: Goldy, Shaindy, Elisha, Chumi, me, Deena, Mordy, Boorie Tzvi, Dov, Yanky, Miriam. We were each two years apart. We had big brown eyes, olive skin, pixie chins, and wildly distinct personalities.

We called our father Tatte. Because we were Yeshivish, we didnt speak a fluent Yiddish, like the Hasidim did, but our English was sprinkled with a few words in that language, when English could not do justice to a concept.

My father had called his own father Dad, but as a child I was not critical enough to reflect on the discrepancy between the little I knew of his history and his insistence that our way of life had always been as it was.

Our three-story home sat on the bottom of a hilly street in a quiet, residential area of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. On Thursday morning, a few hours before Passover would begin, I was standing in my favorite spot: behind the open kitchen door, where my mother hung my fathers clean shirts that were waiting to be ironed. All of his shirts were white, collared, and button-down, but they were not all the same. Some had a checked pattern of shiny white-on-white thread. Some were transparent with wear. Most, however, had hard stays inserted into the collar, two sharp, oblong pieces of cardboard on either side of the neck. My favorite activity at age nine was to stand behind the open door, right index finger thrust backward in my mouth, sucking hard, left hand on a collar stay. Id run my thumb and finger around the edge, bend the cardboard, relishing the dig of the pointed end into the fleshy part of my thumb, and flip the stay while it was still in its pocket. My father, busy with prayer, teaching, lecturing, and counseling, was rarely home. As with God, I treasured him through his rare artifacts.

As the ultra-Orthodox rabbi of the largest semi-Orthodox synagogue in western Pennsylvania, my father devoted his life to bringing his congregants closer to God by urging them to leave their Modern Orthodox ways and embrace Gods true will: the Yeshivish lifestyle. At this, he was successful. Over the years, congregants exchanged knit kippas for black hats, and delicate hair doilies for heavy wigs.

Our house sat kitty-corner to the synagogue, so in the summer, with the windows of the sanctuary cantilevered ajar and our small bathroom window open, I could hear Kaddish while sitting on the toilet. Whenever this happened, Id have to clap my hands over my ears. As an observant Jew, you could not hear Kaddish and not respond, May his great Name be blessed forever and ever, but you also could not speak of God in the bathroom.

Men prayed in the synagogue three times a day, but women went only on Saturday and holiday mornings, and even then, their attendance was not required. So while my father spoke to God from a cherrywood throne beside the holy ark, overlooking a thousand pews, my mother murmured quick morning prayers hidden behind the kitchen door. I was unusual as a child in that I preferred to sneak away on Friday night to sway along to the songs that welcomed the Shabbos. I loved to feel goose bumps prickle my arms as the languorous Lecha Dodi changed halfway into a rollicking tune, almost as much as I loved that moment when the service ended and the room emptied and I could walk through the mens section as if Gods home was my own. I would wait on the side as my father put away his holy books and offered some last words of guidance to his congregants. My shy stance declared that I belonged to the rabbi and, therefore, to God.