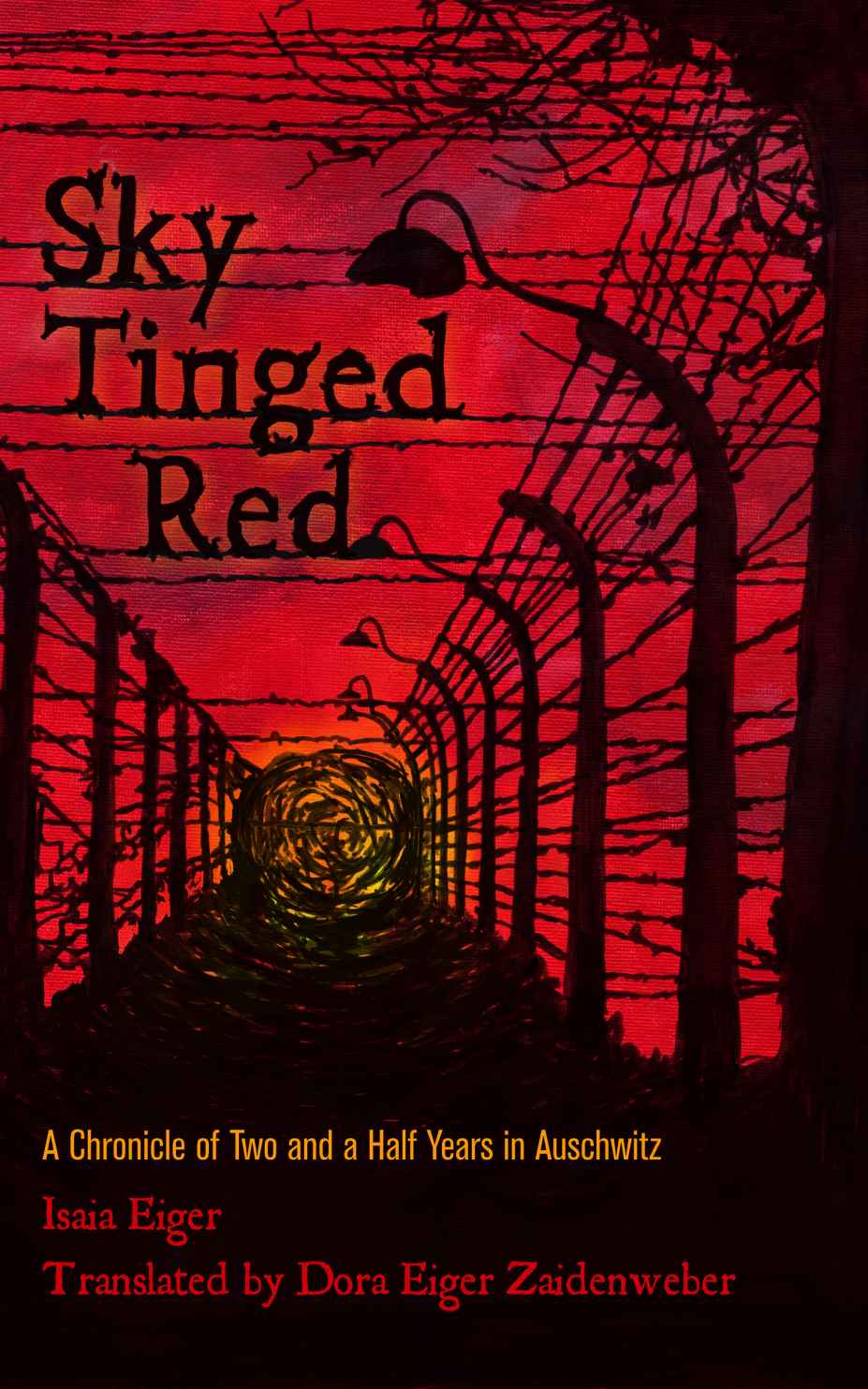

SKY TINGED RED

A Chronicle of Two and a Half Years in Auschwitz

Isaia Eiger

Translated by Dora Eiger Zaidenweber

Edited and Prepared for Publication by

Etan Newman, with assistance from Jonah Newman, Rosanne Zaidenweber, and Claire Buchwald

SKY TINGED RED Copyright 2013 by Rosanne Zaidenweber. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form whatsoever, by photography or xerography or by any other means, by broadcast or transmission, by translation into any kind of language, nor by recording electronically or otherwise, without permission in writing from the author, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in critical articles or reviews.

ISBN: 978-0-9960301-0-6

Library of Congress Number: 2013903445

Printed in the United States of America

First Printing: 2013

Kindle eBook edition: 2014

19 18 17 16 155 4 3 2 1

Cover and Interior Design by: www.renamunster.com

Beavers Pond Press, Inc.

7108 Ohms Lane

Edina, Minnesota 55439

www.beaverspondpress.com

This book is dedicated to the memory of Isaia and Hanna Rose Eiger by their descendants:

David Eiger zl and Barbara (Rabkin) Eiger

Dora Eiger Zaidenweber and Jules Zaidenweber zl

Rosanne and Gary Zaidenweber

Esta Eiger Stecher, Ken and Martin Eiger

Michael and Emily Stecher

Etan and Jonah Newman

Tamar and Anat Naomi Zaidenweber and Gabriel Deacon

Liz and Kim Eiger

With thanks to those who assisted in making this project a reality:

Claire Buchwald

Barbara Impagliazzo

Kashmir Kustanowitz

Rena Mnster

David Sherman

Susan Weinberg

DONT YOU HEAR, DONT YOU KNOW?

Dont you hear the sound of the bells

atop the stately gatehouse?

Dont you hear the sound of weeping and wailing

carried by the wind in stillness?

The cries of squirming children calling for their mothers breasts and arms

The groans of grandmothers and grandfathers as they breathe their last breath?

Dont you see the fire and smoke, the clouds and the sky, tinged red?

Dont you see the inferno that is burning there?

It extinguishes all life in a fiery death

It sends forth the flames, high to the heavens

Merrily aloft, its tongues of fire

Throats choke, human bodies burn, and the ghosts and demons dance joyfully.

Dont you know about the dead and the extermination chambers,

where people are being poisoned and suffocated?

Dont you know about the terrible suffering where people live, crowded together in

despair, fear, deprivation, and dread?

And when the chamber fills with gas they gasp to take a last breath before the poison

engulfs them.

Dont you feel the storm thats raining down, that threatens to engulf the world?

A fire started by pirates and robbers

A fire that rages, that knows no borders.

It destroys all in its waypeople, communities, and nations

Dont you hear the voice of the Ruler of the Universe

Who calls from the heavenly abode to warn:

Whoever tries to rule or destroy my people will suffer my wrath, shame, and mockery.

Isaia Eiger

Birkenau, 1943-1944

TRANSLATORS PREFACE

When this is all over, the world will find it hard to believe that it really happened, a Jewish historian is quoted as saying in the camps. He did not live to find out how truly prophetic his words were. Detractors have tried to question and deniers to deny that such atrocities could have happened in 20th century Europe and be perpetrated by a civilized nation such as Germany was. But it is, in fact, because of where and when it happenedbecause a country like Germany could be turned into a state of unimaginable genocide in the middle of the 20th centurythat memoirs like these continue to be important, more than 65 years after the end of World War II. The Holocaust was the harbinger for things to come. The legacy of the Holocaust has been a century of unparalleled violence and the disregard for human rights and human life.

At the same time, the Holocaust is a unique period in history, one which is not comparable to any other instance of genocide this world has seen. Surviving in an extermination camp such as Auschwitz was not an option for Jews; death was a certainty. It came swiftly for some and despairingly slow for others. This unimaginable place was so unlike anything that has ever existed on this planet; it remains as unreal today as it did to those whose destiny it became all those years ago and those who lived to try to describe it. In this depository of nations, people were pitted against each other by ethnicity and religion as well as ancient hatreds. The murderous oppressors bought loyalty and collaboration by dispensing favors and higher standing. The Jews were brought to Auschwitz after a period of deprivation, deception, and dehumanization, most to be put to death upon arrival. Those left alive as slaves suffered hardships beyond endurance: hunger, harsh elements, illness, and cruel beatings. At the end, death was always looming. Fear and worry about loved ones added to the state of despair. It was easier to give up than to carry on. No one knows how much courage it took to do either, unless one was there. My father was there and he knew. As was I.

My father wrote his memoir of Auschwitz in late 1945 and 1946, with the experiences of the camp still fresh in his mind. He was then 48 years old. He wrote what he saw and heard around him: human stories as diverse and different as people are, human behavior from the highest and most noble to the lowest and most base. He chose to write in Yiddish, the language used by and accessible to the Jewish communities living in countries around the world for whom his record was intended. This was the language of his and preceding generations, which provided a link between the widely dispersed Jews of the Diaspora. But things were changing. The younger generation was not using Yiddish, but rather the language of the surrounding culture in which they were being educated. This process was accelerated after the Holocaust and the establishment of the State of Israel, when Hebrew again became a living language.

Before the war, the Eiger family had lived in the city of Radom for generations. Radom, a town of about 100,000 with a Jewish community numbering 25,000, was an industrial city 60 miles from Warsaw. My father was a successful accountant, a well-respected member of the Jewish community and the community-at-large. Our small family was made up of my parents, my brother David, and myself. My father was a man of moderation and conciliation, quietly assertive and persuasive. His counsel and advice were widely sought, both professionally and privately. He was a renaissance man, a writer and an artist. He could build things from scraps; he could fix anything. He was a teacher and lifelong learner. He was fluent in Polish, Yiddish, German, Hebrew and later in English, and conversant in French and Russian.

My fondest memories from childhood run like a video in my mind. We spent summers in Garbatka, a village not far from Radom, with many of our friends. On Friday afternoons, all the kids went to the little railroad station to greet the fathers arriving from the city for the weekends. For us, the Eiger kids, my fathers arrival signaled non-stop fun. He took us swimming in the village pond and, like a pied piper, he led a bunch of us kids on nature hikes. We picked wildflowers and dried them, pressed between pages of discarded magazines, to bring back to school in the fall. My father knew the names of the flowers and the trees from which the leaves came. Most exciting were the few times he took us deep into the woods with baskets to pick wild berries and mushrooms. He taught us to recognize the edible from the potentially poisonous. At the end of the day we returned to the cabins tired, happy, and full of anticipation as our mushrooms were cooked for supper. Recapturing these precious memories brings a smile to my face all these years later, but it also reopens the deep wound in my heart.