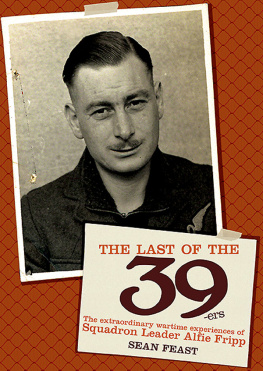

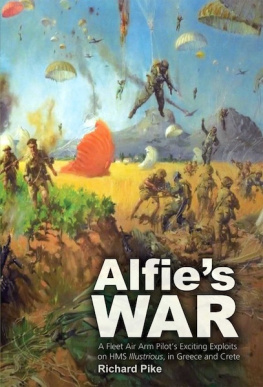

In 2009 a group of ex-prisoners of war visited the site of Stalag Luft III at Sagan in Poland for the sixty-fifth anniversary of the Great Escape. The press came too and quickly identified a character, the impish Alfie. Not only was Alfie a character but he was also a 39-er, shot down and captured on October 16, 1939. So Alfie became the focus for their reporting of our visit. Television became interested in his story, and Alfie made further visits to Sagan, one in the company of Sir David Jason. He was a natural for television with his looks and sly humour. He thrived on it.

But Alfie had a serious side too as is manifest in this book. His death in January, when the book was only part written, was a setback for its author but Sean Feast had drawn from Alfie and his family and friends enough material to complete his splendid story, a work that catches Alfies lively spirit and reflects it throughout the book.

In the prison camps in which we were held, Alfie was a prominent figure. His appearance in the barracks was always welcome because Alfie was in charge of Red Cross food parcels. But, much more than that, he was our Red Cross representative. It was he who sent requests for sporting gear, musical instruments, books and much else, he who maintained a meticulous correspondence with the Red Cross, reporting on health and other aspects of life in the camp. Sean has included some of Alfies letters. They are impressive, showing a conscientious and thoughtful man who would do anything to improve the lot of his fellow captives.

Alfie also played a part in the camp intelligence. The camp leader, the magnificent James Dixie Deans, was able to spirit information to MI9 in London; Alfie and Sammy Panton, who was in charge of the post, worked together when mail came in, especially parcels of which they had been notified to look out for and in which information and escape material were hidden. Alfie never had time to be bored: if he wasnt at the railhead collecting parcels, supervising their transport to the camp and in due course personally delivering them to the barracks, or dealing with the Red Cross or sneaking parcels from the sight of German censors, he was rehearsing for an appearance on the Stalag stage.

Alfie was a remarkable man and Sean has been inspired to write, what for me is a memorable book

Calton Younger

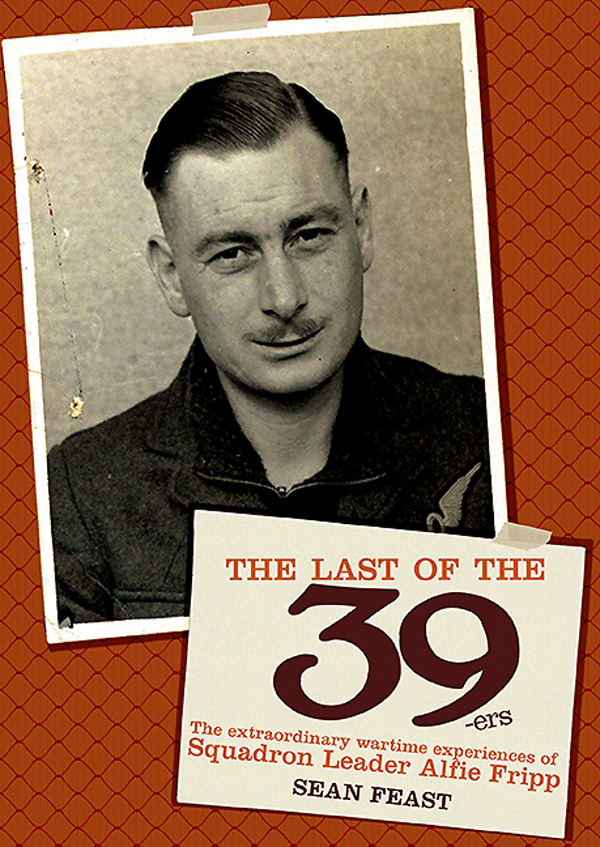

I was introduced to Alfie Fripp through the good auspices of Colin Higgs, a fellow author and enthusiast, in the late summer of 2012. Having seen David Jasons documentary on the Great Escape, I was of course aware of Alfie, but had not until that time had the pleasure of meeting him. Colin told me that Alfie was interested in working with an author to help write his autobiography but had not, until that time, come across anybody he especially got on with!

It was therefore with some trepidation that I drove down to the south coast to meet this gallant airman, conscious of the fact that I could swiftly join the ranks of those who had already been seen and deemed not up to the mark. I need not have worried. Alfie was charm personified and particularly pleased that I not only knew but had previously written about his first Blenheim pilot, Johnnie Greenleaf, who had also been his best man. It was rewarding to be able to tell this distinguished gentleman a little about Johnnies wartime service, and I was only too pleased to present Alfie with a copy of The Pathfinder Companion (Grub Street, 2012) with mentions of his former friend and colleague. I think it was this, perhaps more than anything else, that sealed our partnership and I was eager to get Alfies story underway.

The usual order of things (at least for me) is to conduct a series of interviews and complement those interviews with concurrent research, going back over what has been said to check the facts, dates, times, personalities etc as accurately as feasible and against first source and contemporary documents (wherever possible). We had completed the third of these interview sessions when Alfie was taken ill with what seemed to be an innocuous ear infection. I was not especially alarmed; we had reached the stage in Alfies story when he had been shot down and captured, and I was very much looking forward to hearing more of his adventures in the camps that he had already outlined when I received a phone call I had been dreading. Alfie had taken off on his final flight and would not be returning.

This left me in a little bit of a quandary. Alfies story was always meant to be an autobiography, with me in the background to allow the great man to take the deserving centre stage. But I knew it would be wrong to invent words that had never been spoken, or guess at feelings that had never been expressed. With the full support of his family, and my publisher, I was asked if I would finish Alfies story, and do so as a biography using as many of Alfies actual words, thoughts and expressions as possible.

With my first-hand notes, and a selection of Fripp family archive recordings, I was able to bring together the missing components into what I hope is a flowing narrative. Colin Higgs again also came to the rescue by allowing me access to many hours of interviews he had recorded with Alfie only a few months earlier. Friends and family also introduced me to former Kriegies Cal Younger, Andy Wiseman, Charles Clarke and Eric Hookings who were able to give me valuable insight into what life must have been like for Alfie in the camps. So many people were eager to help that it confirmed, if any such confirmation was needed, that Alfies story had to be finished, so that others might recognise the achievements of a man who came to be known as the last of the 39-ers.

I hope my critics will look favourably on this work and understand the path I was obliged to take, and my reasons for doing so. I hope my reader will agree with me that Alfies story is a remarkable one, and it is a great pity that he did not live long enough to enjoy its publication, and a few precious moments in the limelight that might have resulted.

Sean Feast

Sarratt, Hertfordshire

October 2013

Sergeant Alfie Fripp, a recently-qualified observer with 57 Squadron, had no intention of dying that day, or any other day for that matter. But on the morning of October 16, 1939, he came frighteningly close.

The war was a little over six weeks old and not a great deal seemed to be happening. The Germans had swept into Poland and scared the Poles and half of Europe with their new Blitzkrieg style of warfare, a lightning war with highly-mobile armour and air support. Alfies squadron had received orders shortly after the general mobilisation to proceed from its peacetime base at Upper Heyford in Oxfordshire to France via Southampton, the advance party setting off on September 12 and the main body following ten days later.