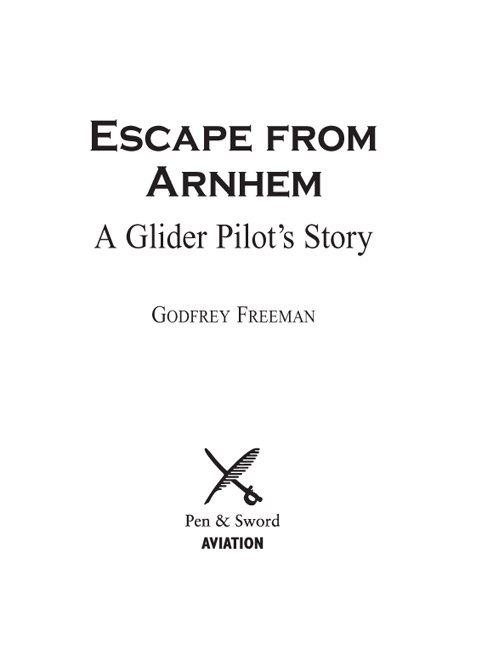

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by

Pen & Sword Aviation

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Godfrey Freeman 2010

ISBN 978 1 84884 147 5

ePub ISBN: 9781844683307

PRC ISBN: 9781844683314

The right of Godfrey Freeman to be identified as Author of this work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the

Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

By MPG

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen &

Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen &

Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth

Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Men fear death as children fear to go in the dark and as that natural

fear in children is increased with tales, so is the other.

Francis Bacon (15611626) Essays, 2. Of Death.

Acknowledgements

This book is dedicated, not least, to all those friends and brave personnel of the Airborne Regiment, past and present, with their special qualities and spirit as well as those who fought and continue to operate equally bravely above, beneath and alongside them.

To name a very special few of them:

Lieutenant Henry Cole

Willem and Hennie Zieglers and family

The Dutch Resistance in its entirety

Major Coke

Pat Mahoney

Major Ian Toler

My thanks extend also, but not limited, to the following for their unfailing support in later days:

Henk Duinhoven and Marion Meffert

My sister Mary Sansbury MBE

My former family, Sheila, Mark and Karl Freeman

Bob Somerscales, GPR Operation Overlord, Normandy

Arthur Proctor GPR and former chief flying instructor of the

Upward Bound Trust, Haddenham Airfield, Thame, Oxon

The Upward Bound Trust [ubt.org.uk] is a voluntary organisation founded by ex-members of the Glider Pilot Regiment in the early 1960s, who continue to introduce young people to the air, in gliders, at a minimal cost.

My final and equally important thanks go to YOU for taking an interest and reading this book.

Contents

Introduction

A growing number of people have at last prevailed upon me to write this history. I have hesitated now for more than thirty-six years for a variety of reasons. Chief among them are two. One is that so many accounts of this kind have come before the public in the post-war years and the second is that I have feared to produce what amounts in current parlance to be no more than an ego trip, a tale of the great I am, a swaggering narrative depicting the author on a heros progress through heroic events.

I make no claim to heroism, nor will my nature ever amount to that of a hero. I wish only to present myself as what I was, a human being in a human situation; a very young and immature human being faced with and perplexed by fears, idealistic conceptions of courage, dread of shame at being judged as less than ones peers, and an obsessive adolescent yearning to prove oneself a Man.

Where then must this story begin? On reflection, the best place to begin seems to be the cellar of the municipal waterworks office building, opposite the northern end of the Colonel Frost Bridge at Arnhem, on the night of 20 September 1944.

CHAPTER 1

The Last Days at Arnhem Bridge

It is dark now. The heavy guns have stopped. The relays of tanks that have been bombarding our building from near point-blank range have ceased fire. Our building is on fire for the fifth time, or is it the sixth? We no longer have any means to put the fire out. There is no water. In our cellars we have over a 120 wounded, twenty-two of them German and a dozen or so Dutch civilians who have taken shelter with us. There is an all-pervading stench of blood, faeces and urine, the only approximation to a latrine being an oil drum full to the brim with stale urine with faeces floating on top. I cannot speak for the state of mind of those about me. I only know that I am in a dream world of exhaustion and have had no adequate sleep for four days and three nights. Last night a paratroop Sergeant Major gave me a Wakey-Wakey pill so that I could take charge of the German prisoners. I am now bewildered and confused but fully aware that the situation is dire. Upstairs, small-arms ammunition is exploding like jumping squibs on Guy Fawkes Night. Next to the Dutch civilians, standing upright like outsize altar candles, are a few rounds of six-pounder anti-tank ammunition abandoned for want of a gun to fire them from. The implication of the fire hazard seems obvious to all but the Dutch, or is their brand of stoicism more deeply ingrained than ours? A paratrooper died in that room yesterday, or was it the day before? He died very quietly, with dignity, almost humbly. Hit in the stomach, he had sat there holding his wound and I had lit a cigarette for him. A little while later, I went back to see how he was getting on. His cigarette had gone out, but as I stooped to relight it for him, he made no movement. Both he and the cigarette, it seemed, had burnt out together.

My last glimpse of Colonel Frost occurred at about this time. White as wax from loss of blood, he lay on a kind of stretcher, defiant and coherent to the last. The bitterness in his voice was unmistakeable as he ordered the white sheet of surrender to be hoisted over the front of the building. Years later I was to be reminded of him when a thoughtless Persian hunter shot a hawk out of the sky. The hunter strode over to finish off the hawk with the butt of his shotgun, and the hawk, with its last dying strength, tore indelible talon scars on the elegant woodwork of the stock. Frosts defiance and the hawks were identical in their intensity. No less indelible were the scars left by Frosts force on the enemy.

Down the cellar steps now comes the first of the Waffen SS. With his sub-machine gun at the ready, he inquires Are you British or American? There is hidden significance in this question, for the American Airborne forces to the south had sworn to avenge the massacre of their comrades at St Mre-glise and were reputed to have taken no prisoners. Were British, I replied. So what? echoed a voice behind me. The SS man shouldered his gun and slapped me on the back as though I were a member of a visiting football team. Tommy! he cried, with a huge grin of combined relief and apparent affection, Tommy! Tommy!

But this was no time to fraternise. The fire was already devouring the building. What happened next might seem to illustrate the futility of war. With no perceptible hesitation and as though they had been training together throughout their service lives, British and German troops combined in a joint rescue operation to clear every living person from the cellars. Doors were ripped off nearby buildings to provide makeshift stretchers. Often mixed pairs of Airborne and SS men struggled together to lug the wounded out from certain death. A Hohenstaufen soldier and I checked the blazing upper floors as far as we could penetrate, and then clattered down to the cellar to find it empty and deserted. As we scampered out through the main entrance, a huge crackling beam crashed to the floor in a shower of sparks not ten paces behind us. Involuntarily, we both spun round to glance back. There was no need for words. We both raced across the road to the grass embankment opposite.

Next page

![Freeman - Pro design patterns in Swift: [learn how to apply classic design patterns to iOS app development using Swift]](/uploads/posts/book/201359/thumbs/freeman-pro-design-patterns-in-swift-learn-how.jpg)