First published in Great Britain in 2002 by

LEO COOPER

an imprint of Pen & Swords Books

47 Church Street, Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

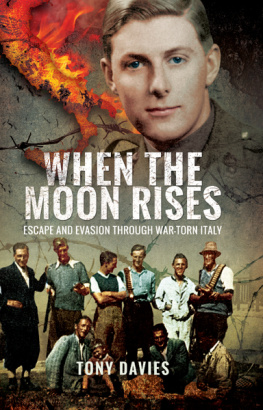

Copyright Tony Johnson 2002

ISBN 0 85052 894 1

eISBN 978 1 78337 910 1

A CIP record for this book is

available from the British Library

Typeset in 11/13pt Sabon by

Phoenix Typesetting, Ilkley, West Yorkshire

Printed in England by CPI UK

To Joyce

Who waited

C ONTENTS

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The task of accurately describing events that occurred more than half a century ago would have been a most daunting exercise were it not for the invaluable assistance provided by many friends and acquaintances, who were able to refresh and supplement a memory dimmed by the passage of time. I am most grateful to them all.

I owe a special thanks to the surviving members of my crew; Geoffrey Hall, Albert Symonds and William Ostaficiuk and my Squadron Commander, Group Captain Dudley Burnside DSO, OBE DFC and Bar (RAF Rtd.) for their most helpful information and advice. Also to my wife Joyce, for her encouragement -and infinite patience.

The Crown Copyright material for this work is reproduced with the kind permission of the Controller of Her Majestys Stationery Office.

F OREWORD

by

Group Captain Dudley Burnside DSO OBE DFC (RAF Rtd),

wartime Officer Commanding 427 and

195 Squadrons, Bomber Command.

It was indeed a great privilege to lead a squadron in Bomber Command in 194243 and again in 194445 and to share the appalling dangers of continuous raids over Germany with that magnificent band of young aircrews whose devotion to duty and outstanding courage are legion and of which the author of this book was a typical example.

As his Commander-in-Chief, Marshal of the Royal Air Force, Sir Arthur Harris, put it these young men carried unceasing war to the enemy against fearful odds for over five years, and for much of that time alone whilst we lacked the means for any other attack.

I know only too well the experience of being coned by searchlights, of being attacked by nightfighters and blasted by flak. But to read such a first-hand account of the terrifying moments immediately following a fatal direct hit, of the aircraft turning upside down before spiralling vertically to earth is not only to bring sharply into focus the incredible luck of those of us who survived one or more tours of operations physically unscathed but to pay the greatest tribute and admiration to those such as Tony Johnson who, having miraculously baled out of his doomed Wellington aircraft, continued to display incredible courage and endurance in very hostile enemy territory.

His description of life as a prisoner of war and his extraordinary adventures during his two escapes will surely serve to remind future generations of the unsurpassed devotion to duty and heroism of wartime aircrews against great odds both in the air and on the ground.

Dudley Burnside

Windsor

Chapter 1

N ASTY P RANG

The unmistakable drone of aircraft engines being run up to operating temperature reverberated through the North Yorkshire countryside in which the farming village of Dalton-on-Tees nestled. The now familiar sound of squadron activity at RAF Croft airfield, situated to the west of the village, was the cue for the local fan club of civilians and servicemen patronizing the busy Crown and Anchor public house, to take their drinks out into the fresh air to watch the aircraft take-off. Some would watch in silence while others would wave frantically as the aircraft roared over the perimeter security fence, some alarmingly low as they lifted into the beautiful April sky. However, there were also those who worked the farms skirting the airfield, and many light sleepers who cursed the day when the Ministry of Defence compulsorily purchased the land to build an airfield which was completed in 1941 for Bomber Command. Despite the fact, apart from most Sundays, there was little or no noise abatement practised on the airfield around bedtime and before noon when the aircraft were air tested, these folk were very much aware that there was a war on and had taken the personnel serving at the bustling RAF Station on their doorstep.

It was late evening on 6 April 1943, and RAF Croft was the base for 427 (Lion) Squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force. The Squadron was one of nine in the recently formed 6 Group RCAF, a group that became operational on 1 January 1943 and was equipped with Vickers Wellington Mk III and Mk X medium bombers.

I was a crew member of one of four Wellington aircraft leaving their dispersal pans and being taxied around the perimeter track to take up the second position in a queue at the end of the runway to wait for its turn to take-off. The four aircraft were about to carry out a night exercise by the codename Bullseye which, in effect, was to simulate a raid on London to give our nightfighter pilots experience at homing in on hostile bombers. More importantly, it was good experience for us rookie crews who had little operational experience over enemy territory: particularly if we lost our bearings in cloud and flew into a barrage of balloons over Leeds, Sheffield or London itself. Quite exciting, really.

Soon the Airfield Controller in his chequered van gave the green light for us to take-off. As the German Luftwaffe monitored our radio frequencies, strict radio silence was observed by Bomber Command operators during aircraft movements to carry out air tests, training or operations against the enemy. The maintenance of radio silence denied the Luftwaffe the means of assessing our strength, the likely flight path of the bomber force, and thus lessened the odds of Luftwaffe nightfighters waiting in ambush to tenaciously defend their Fatherland. That is why the NCO in the chequered van relied upon the Aldis lamp rather than communicate with the pilots on shortwave radio.

Steve, my skipper, released the brakes and eased the throttles forward and the aircraft gathered speed along the runway in the evening dusk. From my position with my head in the astrodome a perspex bubble on top of the fuselage I had an excellent view through 360 degrees. We slowly passed a group of spectators waving us off near the van, gradually increasing speed along the 2,000 yards of reinforced concrete runway. On reaching flying speed we lifted off with plenty of runway to spare, to start to climb after the aircraft that had preceded us on take-off less than a minute before. Once off the ground and without the burden of a bomb load we were not really about to bomb London we climbed fairly rapidly as we circled the airfield to wait to be joined by the remaining two aircraft before setting course.

Standing at the astrodome I had a panoramic view of the airfield as we climbed away from it. I was also able to watch the next Wellington as it took off, and the last aircraft turning onto the runway for its turn to take to the air. As the aircraft following immediately after us left the runway it climbed no more than fifty feet when, suddenly, its port wing dipped as it banked, obviously out of control, and headed in a shallow glide towards the front door of the East Vince Moor farmhouse in the occupation of farmer Pearson and his family. Some seventy feet before it reached the farmhouse, the doomed aircraft was brought to an abrupt halt by a clump of aged elm trees, and disintegrated on impact. Flying debris showered the surrounding area as, in a few breathtaking seconds, the twisted wreck of the aircraft erupted into a blazing inferno as some 700 gallons of high octane aviation fuel ignited, sending a huge fireball into the evening air. I knew that the intense heat would rapidly fuse the light airframe alloys and incinerate those of the five man crew trapped in the instant crematorium who, mercifully, had either been killed outright or knocked unconscious by the terrific force of impact. It seemed incredible to me that in a matter of seconds, on such a pleasant evening, men would die in what was considered an airworthy and air tested aircraft.

Next page