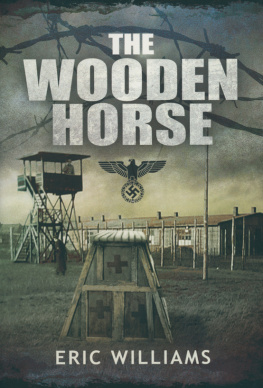

THE

WOODEN

HORSE

THE

WOODEN

HORSE

ERIC WILLIAMS

First published in Great Britain in 1949 by

William Collins Sons & Co Ltd, Glasgow.

Reprinted in 2005 by Pen & Sword Military Classics

Republished in this format in 2013 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Eric Williams, 1949, 1979, 2005 and 2013

ISBN 978 1 78346 241 4

The right of Eric Williams to be identified as Author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

By CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Pen & Sword Discovery, Pen & Sword Politics, Pen & Sword Archaeology,

Pen & Sword Atlas, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime,

Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Claymore Press, Remember When,

Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

For Sibyl

again as always

There was things which he stretched,

but mainly he told the truth

Mark Twain

Explanation

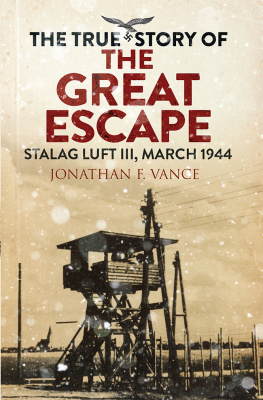

During the Second World War three British officers escaped from a German prison camp by digging a tunnel whose entrance they concealed beneath a wooden vaulting horse. All three reached home.

I was one of them. I had been captured a year earlier, three days after my Stirling bomber was shot down in a raid on Duisburg in the Ruhr. Although captain of the aircraft, I was not the pilot but the observer, and while I was grounded in Germany observers became redundant. Thanks to the inventions of the boffins, navigating and bomb-aiming could now be done more efficiently by instruments operated by highly trained specialists.

On my return to England I reported to the Air Ministry, but they patently did not know what to do with me. I applied for the pilots course which I had been too old to take at the beginning of the war. They said they would consider the application and sent me on extended leave. This was broken at intervals by tours of airfields around the country where I lectured the new breed of aircrews on what to expect if shot down over enemy territory. For this I was given an allocation of petrol coupons which enabled me to visit the families of fellow-prisoners who had asked me to take home messages of comfort and reassurance. The parents, wives and sweethearts asked so many questions that I determined to write a book describing the day-to-day life of a prisoner of war.

Military Intelligence had decreed that prison camps were on the Secret List. Even though I might, and did, know what was safe to write about and what was not, no factual material was to be published. I well remember the peremptory summons to one of those Home Counties mansions so dear to Military Intelligence, and the fury of the Brigadier when I told him that I intended to publish the book as fiction.

On leave in the 1944 London of buzz-bombs, still waiting word from the Air Ministry about the pilots course, I sat down and wrote the story of my last raid, capture and life in three German camps. I omitted or deliberately made misleading any mention of escape, and suppressed all information of possible use to the enemy. Writing in the form of a novel I was able to reduce the number of background characters and to select and highlight those incidents which seemed to me most valid. I found it convenient to describe my own actions, thoughts and emotions by writing in the third person and calling myself Peter Howard. My other characters, though typical, were not based on individual prisoners. The description of life in the camps where I had been held was as true as I could make it.

The finished novel was short, about 60,000 words. Its title was Goon In The Block, the warning cry with which the P.O.W. broadcast the arrival of a German guard. I sent the typescript to Jonathan Cape. He accepted it within forty-eight hours and published it in the early summer of 1945 when hundreds of thousands of prisoners held in Germany were beginning to stream home. Although the whole print was sold in the first week, wartime paper rationing precluded a reprint.

Inspired by Goon In The Blocks modest success and the encouraging reviews, I began to write my escape story. The war in Europe was nearly over but I was serving in the RAF and the Official Secrets Act was still in force. For this reason, and because I liked the freedom it gave me, I again wrote in the form of a novel. Again my alter ego was Peter Howard. My fellow-escapers Michael Codner and Oliver Philpot emerged thinly disguised as John Clinton and Philip Rowe. The other prisoners portrayed are more difficult to identify; but ex-inmates of Stalag-Luft III may recognize Tommy Calnan, Aidan Crawley and a few other originals.

Writing the story as fiction gave me perhaps too much freedom. When faced with the problem of not knowing what had been going on around me or forgetting exactly what happened when I was able to take, and happily took, a few liberties with facts. The horse, the tunnel, the break from the camp, the train journey across enemy territory, the stay in Stettin, our contacts with French workers and the escape from Germany itself were, and are today, vivid in my memory. After a night of seasickness in the stinking bilges of a Baltic freighter events became a bit confused. Hidden ashore in Copenhagen as bewildered protgs of a teenage Danish seaman, Mike and I no longer had any say in our destiny. Following the thrill of running our own lives, of being fugitives in the midst of the enemy, the final crossing to neutral Sweden seemed a tame way to end the story. Accordingly I invented a climax which, I thought, matched the preceding pages for excitement.

Fair enough.

The escape story, which I called The Sagan Horse, was nearly 200,000 words long. I sent it to Jonathan Cape whose contract for Goon In The Block had given him an option on my next book. He turned it down, saying that no one wanted to read about the war. As it incorporated much background material from Goon In The Block I retrieved rights, and was free to offer the new book to another publisher.

I offered it, in all, to seven publishers. It was rejected by every one each time on the grounds that war books were finished. Each time I got it back I worked on it before sending it out again.

I wrote the first version on the various airfields where I trained as a pilot and on board troopships on my way back from the Far East where I had been posted to recover Allied prisoners from the Japanese. On demobilization, in common with a million others, I had to find a way of earning a living. I was the richer by all of 200 from Goon In The Block and Cape had rejected its successor. My pre-war employers were committed to finding good jobs for their ex-Servicemen. Because of my somewhat ephemeral literary experience they offered to make me book-buyer for their seven provincial department stores.

Next page