Jon Holloway

Helena Merriman is a broadcast journalist who presented and produced Tunnel 29, BBC Radio 4s new podcast about a miraculous escape under the Berlin Wall. She is also the co-creator of British Podcast Awardwinning series The Inquiry, and previously worked as a reporter for the BBC in the Middle East. She lives in London, UK.

Copyright 2021 by Hugely Limited and the BBC

Cover design by Pete Garceau

Cover images Lehnartz / Ullstein Bild via Getty Images

Cover copyright 2021 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

PublicAffairs

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.publicaffairsbooks.com

@Public_Affairs

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Hodder & Stoughton, an Hachette UK Company

First US Edition: August 2021

By arrangement with the BBC

The BBC logo is a trade mark of the British Broadcasting Corporation and is used under licence.

BBC logo BBC 1996

Published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The PublicAffairs name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call () - 6591 .

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Typeset in Bembo MT Pro by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd, Falkirk, Stirlingshire

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021936581

ISBNs: -- 5417 - 8884 - (hardcover), -- 5417 - 8882 - (ebook)

E3-20210709-JV-NF-ORI

For Henry, Matilda and Sam

And my childhood family

Like all walls it was ambiguous, two-faced. What was inside it and what was outside it depended upon which side you were on.

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed

W HEN I FIRST meet him, I can barely talk. Its eight flights up to Joachims apartment and by the time Im up there, holding my microphone to record our first meeting, Im puffed out.

Joachim laughs and invites me in. Id phoned him a week earlier (in October 2018), said I wanted to come to Berlin to ask some questions about something hed done almost sixty years ago. The phone call was short, his English was limited, my German was even more limited, but in that conversation one thing struck me. Most of the people Ive interviewed in my career as a journalist tend to generalise, summing up their experiences through their emotions. Joachim was different: he spoke in details, remembered smells, sounds, measurements, colours. I was intrigued and asked if I could come and meet him the following week. He said yes.

We walk round his apartment. Its light and airy, full of plants, and his shelves are dotted with puppets, buddha statues and porcelain cats. Above the door to the bathroom theres a white enamel plate with the number seven on, wrenched off the wall by Joachim in the middle of the night, he tells me, from an apartment block on the other side of the city. The apartment block where it all happened.

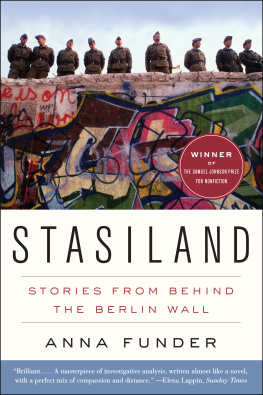

We walk over to the full-length windows and I admire the panoramic view, the city coming to life below us in the early winter sun. Joachims flat is on the edge of things, where the apartment blocks and high-rises of inner-city Berlin meet the conifers and pines of Grunewald forest. We stand there a moment and Joachim gestures in front of us, pointing into the distance where the Berlin Wall once stood. I think of those images from 1989, the night when people climbed on top of the Wall, danced on the concrete, then hacked into it with hammers, pulling it down. Every year that ends in a nine, we replay that moment, but Ive always been more interested in the other end of the Berlin Wall story: 1961. The year it was built.

What happens when a government builds a barrier that cuts a city or country in half? That question was in the back of my mind when I was working as a journalist in Egypt and the police built a ten-foot-wall in front of the Ministry of Interior and protesters pulled it down. It was in my mind when I was living in Jerusalem and spent hours queueing at checkpoints to cross into Gaza or the West Bank. People talk about the fall of the Berlin Wall as the end of an era, and in one way it was: it marked the end of the Cold War. But a new era soon began: the age of walls. Right now, walls are in fashion over seventy countries (a third of the world) have some kind of barrier or fence. Some run along borders, others separate areas within countries, or even within cities. Whatever their scale, with their guard-towers, death strips and alarm systems, many draw inspiration from the Wall of all walls the one built in Berlin in the summer of 1961.

Joachim gestures to a table where the two of us sit. I clip a microphone onto Joachims navy fleece and ask what he ate for breakfast, the standard radio question to check his levels. As he tells me about his smoothie and scrambled egg, I jack the microphone right up. His voice is quiet, modest. Up close I notice his elfin ears, his bright blue eyes that squint closed when he smiles. I calculate his age: eighty. Then I press record.

That evening we talked for three hours. I returned the next day and we talked for five. It went on like this for over a week, me asking questions, Joachim answering them with breathtaking detail, his wife bringing cups of tea, gently squeezing his shoulder as she set them down. Over the following three years, I tracked down others involved in this story, interviewed them and read their letters and diaries, then discovered thousands of Stasi files that give you the kind of minute-by-minute detail that, as a journalist, you usually only dream of. I discovered a replica tunnel, the same dimensions as Tunnel 29, and recorded inside it; I wanted to know what it felt like to be underground, digging in the space the width of a coffin, and wondered why someone would choose to spend so long down here.

This research changed what I thought I knew about many things: the end of the Second World War, the beginning of the Cold War, the building of the Berlin Wall, the birth of TV news, and what it means to become a spy and betray the people around you. The result is this book.

Any dialogue that appears comes directly from those interviews as well as from Stasi meeting reports and interrogations, and Ive drawn on oral histories, maps, memoirs, court-papers, declassified CIA and State Department files, and print, TV and radio reports to fact-check names and dates as well as for additional research. Any errors are mine.

When Joachim Rudolph and his family walked to Berlin in 1945 , they joined one of the largest forced migrations in human history. Arthur Grimm/ullstein bild via Getty Images