Contents

Guide

Australia

HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty. Ltd.

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street

Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

www.harpercollins.com.au

Canada

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

Bay Adelaide Centre, East Tower

22 Adelaide Street West, 41st Floor

Toronto, Ontario, M5H 4E3

www.harpercollins.ca

India

HarperCollins India

A 75, Sector 57

Noida

Uttar Pradesh 201 301

www.harpercollins.co.in

New Zealand

HarperCollins Publishers New Zealand

Unit D1, 63 Apollo Drive

Rosedale 0632

Auckland, New Zealand

www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF, UK

www.harpercollins.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

195 Broadway

New York, NY 10007

www.harpercollins.com

Through the Perilous Fight: Six Weeks That Saved the Nation

The Pentagon: A History

BETRAYAL IN BERLIN . Copyright 2019 by Steve Vogel. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

FIRST EDITION

Title page photograph courtesy of the CIA

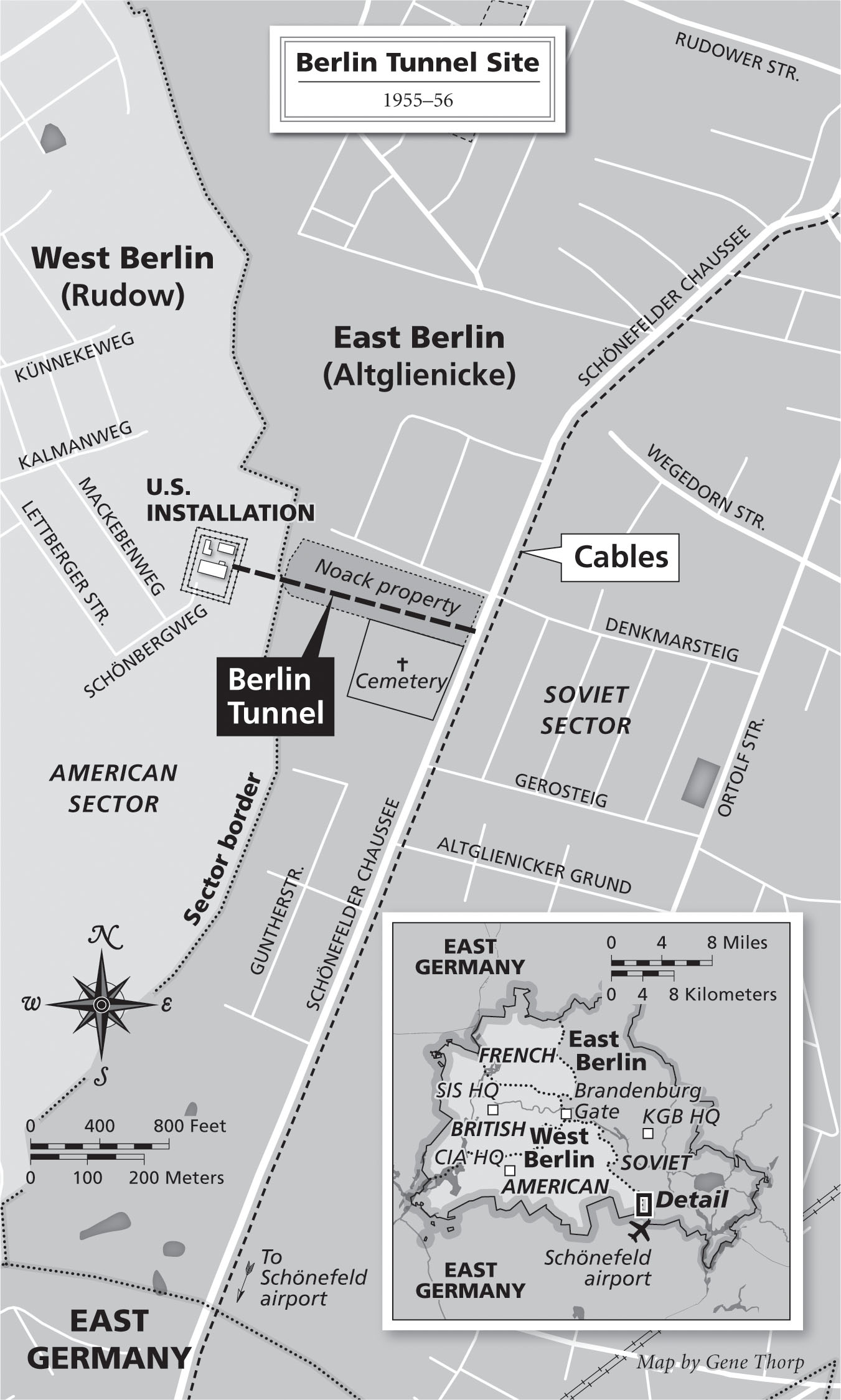

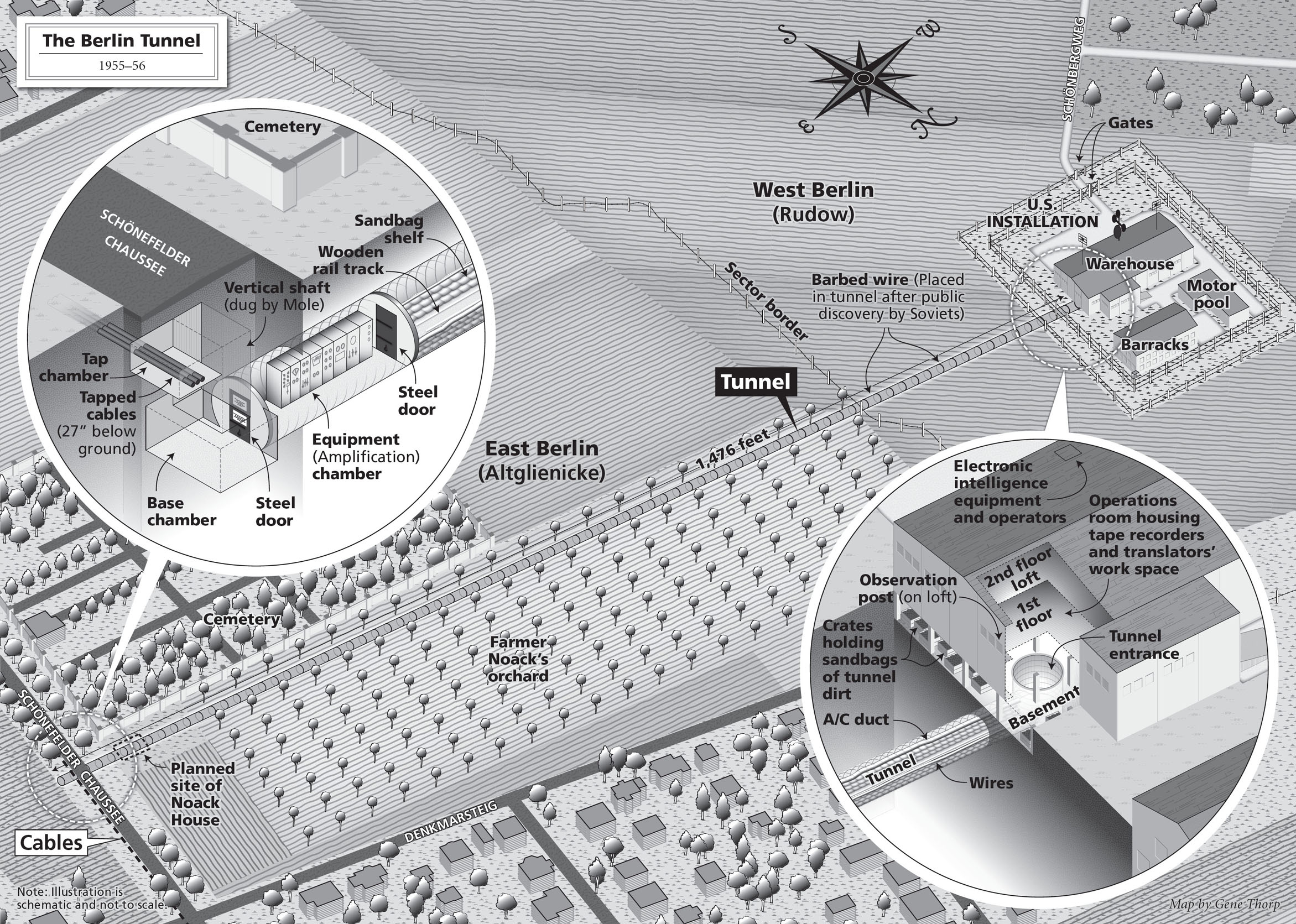

Front matter maps by Gene Thorp

Digital Edition SEPTEMBER 2019 ISBN: 978-0-06-244961-0

Print ISBN: 978-0-06-244962-7

To the undying friendship and devoted service of three happy warriors:

Don Vogel, Ben Pepper, and Gus Hathaway

Contents

KOREA, SUNDAY, JULY 2, 1950

A t midnight, the British, American, and French prisoners were taken from the Seoul police headquarters and bundled into the back of a North Korean army truck, guarded by soldiers holding submachine guns and bayonet-tipped rifles. The captives, including diplomats, missionaries, and businessmen, had been rounded up when the North Korean army launched a surprise attack on the south a week earlier and swept into the South Korean capital. When the British diplomats had asked to bring clothes for the journey, they were told, rather ominously, that it would not be necessary.

The prisoners were taken through a landscape of burned villages and bomb craters, the air pungent from the smell of rotting corpses. As they drove, the North Korean officer escorting the captives practiced with his newly issued Russian weapon, firing blindly into the night and further fraying nerves. For an hour, the truck climbed a mountain road, and then continued down into a remote valley, where it came to a halt. George Blake, vice-consul for the British legation in Seoul, exchanged looks with his fellow prisoners. All had the same realization: They had been taken to this isolated spot to be summarily executed. Blake saw that the truck was carrying a spare barrel of gasoline and concluded that it would be used to burn their bodies afterwards. Herbert Lord, a British citizen who served as commissioner for the Salvation Army in Korea, thought it appropriate to lead the group in a short prayer.

Unbeknownst to his captors, as well as to almost all of his fellow prisoners, Blakes diplomatic title was cover for his true role as chief of station in South Korea for the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS)also known as MI6. The son of a Dutch woman and a Turkish subject who had fought for the British Empire, Blake had a cosmopolitan background, experience in hazardous situations, and a facility for languagesRussian, German, French, and Dutch, among othersthat made him a natural for espionage. Just twenty-eight years old, he had already survived great dangers in Nazi-occupied Europe. After the German conquest of the Netherlands in 1940, Blake, then a schoolboy, served heroically, delivering messages for the Dutch resistance. In 1942, he made a daring escape through France and Spain before he made it to England. There, he joined the Royal Navy and was recruited by the SIS, and at wars end was dispatched to occupied Germany to gather intelligence on the Soviet Red Army. In 1949, he was sent to South Korea, tasked with trying to establish an intelligence network to spy on the Soviets in the Far East.

The North Korean invasion on June 25, 1950, had triggered the Cold Wars first armed conflict. The United States, with the support of the United Nations, had rushed troops to defend South Korea, but the unprepared Americans were knocked back almost to the sea by overwhelming North Korean force. Westerners based in Korea were caught up in the chaos accompanying the brutal and dangerous first days of the war.

Now it had come to this. Sitting in the back of the truck awaiting execution, Blake was forcibly struck with a bitter realization of how perfectly useless his death would be. After an excruciating wait of twenty minutes, a jeep carrying two North Korean army officers arrived. But instead of overseeing an execution, the officers ordered the vehicles to resume driving north. The prisoners were alive, but their ordeal was only beginning.

* * *

Blake and his fellow captives were taken to the northern town of Manpo, nestled on the banks of the Yalu River on the frontier with Manchuria. Over several months, their group grew to include Turkish and White Russian businessmen and their families who had been detained in Seoul. More Western clergy, including elderly French priests and nuns, were also rounded up from across Korea, as well as several journalists, among them Philip Deane, the dashing and cocky correspondent covering the war for the London Observer.

The civilian prisoners, now numbering about 70, were being held near a camp holding 777 American prisoners of warsoldiers from the 24th Infantry Division units overrun by the North Koreans at the start of the war. The POWs were in dreadful condition, still wearing the summer fatigues in which they had been captured during the initial weeks of the war, and many now without shoes. These were not battle-hardened veterans of World War II; most were poorly trained and badly equipped conscripts who had been on cushy occupation duty in Japan before being sent into the fight. They had been taken out of this paradise and thrown into the hell of the Korean War, Blake observed. The civilian prisoners were shocked by the haggard and emaciated appearance of the POWs, many of them infested with lice. These ragged, dirty, hollow-eyed men did not look like any American soldiers that I had ever seen, recalled Larry Zellers, a lanky Methodist missionary from Texas who had served as an airman in World War II.

But in mid-September, the prospects for all the Western captives suddenly soared. One morning while Zellers was drawing water at a well, a brave Korean schoolboy surreptitiously handed him a note reporting that General Douglas MacArthur, commander of UN forces, had turned the war around with a landing behind enemy lines at Inchon, triggering a massive North Korean retreat with American and UN troops in pursuit. Two weeks later, the prisoners were overjoyed by news that MacArthur had recaptured Seoul and was driving north.

Next page