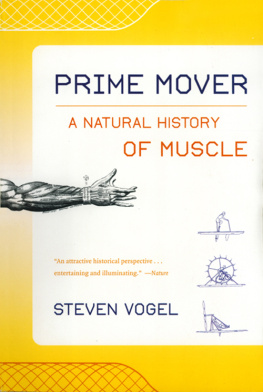

Copyright 2001 by Steven Vogel

All rights reserved

First published as a Norton paperback 2003

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write

to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue,

New York, NY 10110

Book design by Brooke Koven

Production manager: Julia Druskin

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE PRINTED EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Vogel, Steven, 1940

Prime mover : a natural history of muscle / Steven Vogel; illustrated by

Annette deFerrari and the author.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-393-02126-2

1. Muscles. I. Title.

QP321.V64 2002

612.74dc21 2001044842

ISBN 0-393-32463-X pbk.

ISBN 978-0-393-24731-2 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London

W1T 3QT

to Roger, Frances, Booth, and Avery, who, wearing

my genes, must now take charge of my fitness

We humans remain animals. Biology talks about us all, something that can create a lot of uneasinessor worse. It implies constraints on human aspirations, constraints that may loom large or small, depending on ones political and social outlook. On the one hand, we worry about how much our genes might set our individual and collective courses; on the other, we use nonhuman animals as surrogates for investigating our illnesses. For the biologist, our animal nature is second nature, even an opportunity. It provides a larger arena in which to explore how we do what we do, with the we then transcending the temporal and structural boundaries of our species.

Thats the intent here. But youll encounter nothing so controversial as arguments about inherited behavioral predilections. No, I just want to take a piece of our biological nature, the flesh of flesh and blood, and explore how it works and how we work with it. I mean to argue the general message that because we are animals, a biologically based view can shed light on our human world. My last book, Cats Paws and Catapults, argued the same point from a different vantage point. It used biomechanics as a base line from which to explore why we make the kinds of things we do. Here I ask what muscle physiology may reveal about human history, prehistory, and culture.

Muscle has been our sole engine for most of our time on earth. Our muscle differs only a little from that found elsewhere in the animal kingdom. The same stuff propels water flea and whale. With it we walk and run and climb and swim; we lift heavy weights and manipulate tiny screws; we bend things, twist things, kick and bite things. But we dont flynor does any other animal as heavy as a humanat least without an extraordinary prosthesis. Nor can we burrow like an earthworm or jet like a squid or jellyfish, even if were near the top of the heap for the overall diversity of our muscle-powered activities.

Our muscles arent the most forceful or the hardest working, but on both accounts they come close to natures best, and were well endowed, devoting almost half our body mass to muscle. We can paddle boats, pull carts, push wheelbarrows, pedal bicycles, carry each other on litters and sedan chairs. In return for food and breeding opportunities, our bovids, equids, and camelids contribute their muscular efforts to tasks we choose. Both the pyramids of Egypt and the Great Wall of China represent muscular accomplishments as much as they do social and technological ones. In both cases human muscle did most of the job.

Thus muscle provides a rich and multifaceted tale. I begin by explaining what we know about how it works and how weve come to know what we know. The remainder of the book ties the operation of this engine to the tasks it does, looking first at how the basic engine can be hooked onto skeletons to perform diverse activities. It then moves farther afield to consider such things as the design of tools, the harnessing of beasts of burden, the limits to our performance, even our predilection for eating muscle. I hope to make the case that biology, physiology, bio-mechanicsmy interestsmatter in contexts far beyond their immediate scientific domains. Writing the predecessor of this book hooked me on the seductive pleasure of moving out of my scientific box. I nourish the hope that the results of the activity may prove enjoyable and enlightening for others.

Muscle has not yielded its secrets easily. Over the years Ive met quite a few people actively investigating how muscle works at every level from molecules to animals. I can report that without exception they uphold the best of the scientific traditionfrom pure intellectual quality to their attitudes toward their subject and one another. Theyre made in different moldsflamboyant (Szent-Gyrgyi), noisy (Dick Taylor), quiet (Tom McMahon), and so forthto pick people who can no longer take issue with my characterizations. Lesson? Between our interest in people and the tough job of explaining science, perhaps we pay too much attention to disputes and rivalries and areas of scientific work in which theyre prevalent. My forty-year experience as a scientist suggests that the muscle people are closer to the norm.

A large number of people have generously advised me at one point or another in my getting together the present material, explaining things, suggesting sources of information and useful examples, extracting my foot from my mouth. Several afternoon tea drinkers helped throughout the whole enterprise: John Gregg, Daniel Livingstone, and Fred Nijhout, and Knut Schmidt-Nielsen, in particular. Mike Reedy, in whose company I regularly work my muscles and cardiovascular equipment, survived my repeated questions about muscle microstructure and the people working on muscle. More specific items came from Al Buehler, Peter Burian, Marjorie Dosik, Bob Full, Jeff Goldman, Lew Greenwald, Barbara Grubb, Bill Holley, Abdul Lateef, George Newton, Rad Radhakrishnan, Kalman Schulgasser, Anne Scott, Lloyd Trefethen, Steve Wainwright, and Martha Weiss, although not all these folks realized just what they were aiding.

In particular, I owe much to my anthropological colleague, Steve Churchill, and my ever-tolerant spouse, Jane, each of whom annotated drafts of the entire manuscript. And to my editor at W. W. Norton, Edwin Barberinstigator, adviser, and one of my three best writing teachers. If, as he says, this manuscript came in cleaner and clearer than my last, he should take muchmaybe mostof the credit.

by Nature (copyright 1986, Macmillan Magazines Limited). I am especially indebted to Mary Reedy, who contributed all the electron micrographs.

Steven Vogel

Durham, North Carolina

Prime Mover

O F THE WEIGHT OF A HUMAN IN DECENT SHAPEALL TOO few of usmuscle makes up fully 40 percent. Not blood, bone, brain, or liver contributes as much; only together do they add up to our weight of muscle. Moreover, all that muscle does just one task: It makes the chemical fuel that originally came from our food produce force and motion. It does neither more nor less than what we ask of the combustion engines of our cars and airplanes. As in the engines of our technology, its imperfect efficiency makes it get warm, a nuisance when we work hard in warm weather but nice enough as we jump around or shiver to offset the cold.

In power efficiencyhow much work it can do for a given amount of fuelmuscle differs little from those combustion engines. In weight efficiencyhow much work a given weight of muscle can do in a given timeit compares well with automobile engines but suffers badly when put up against a good jet turbine. Still, this is one remarkable device. Nature perfected it around a billion years ago (give or take a few hundred million), launching multicellular animals on our glorious trajectory. It powers ant and elephant alike, so alike that only a trained eye can see the subtle differences between their muscles when bits are viewed under a microscope. Flies fly with it; clams clam up with it.

Next page