One of the massive K-42 Boston Cameras (Big Bertha/Pie Face) with its 240in lens is on public display at the US Air Force Museum in Ohio. (Photo: USAF)

The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors alone and should not be taken to represent those of Her Majestys Government, MoD, HM Armed Forces or any government agency.

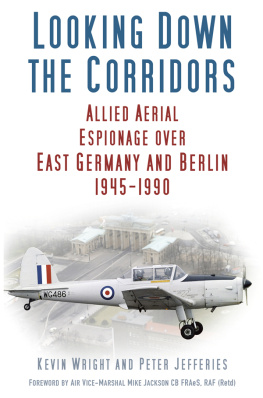

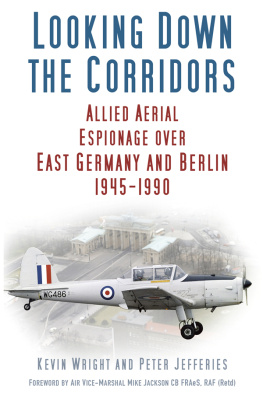

Cover illustration

Front: Chipmunk over Brandenburg Gate. (Crown Copyright)

First published in 2015

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

Kevin Wright and Peter Jefferies, 2017

The right of Kevin Wright and Peter Jefferies to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 6458 6

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

C ONTENTS

F OREWORD BY A IR V ICE- M ARSHAL M IKE J ACKSON CB FRA E S, RAF (R ETD )

Formerly Director General Intelligence and Geographic Resources, Defence Intelligence Staff (DIS); OC Joint Air Reconnaissance Intelligence Centre; Defence and Air Attach Warsaw; OC 60 Squadron

Sun Tzu wrote in his famous treatise On the Art of War that tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat, while strategy without tactics is the slowest way to victory. In the prologue to this book you see the central theme rightly described as reconnaissance operations being part of an intelligence campaign. Air reconnaissance is a collection tactic which helps to feed an intelligence strategy, and each connects with the other in a continuous relationship of supply and demand, which Sun Tzu would have recognised.

Looking Down the Corridors describes collection operations which were amongst many in the strategic intelligence campaign to penetrate the secrets of the Warsaw Pact during the Cold War. They were complementary with other aerial reconnaissance activity, as well as with intelligence collection work on the ground in particular by the Allied Military Liaison Missions accredited to the Soviet Forces in Berlin, and by the Defence Attachs in neighbouring Warsaw Pact countries.

However, these were exceptionally significant operations because they took place in such a target rich environment, and because they could provide evidence that could not be surpassed. The Prague Spring case is a perfect example of how they could impact at the very highest levels, and respond in real time. More often the Corridor missions satisfied specific intelligence requirements, to update and maintain the long-term Indicators and Warning watch, and to provide the fine detail that helped the technical intelligence community to analyse and assess the weapons and systems capabilities of the other side. While this was less dramatic it was also vital work, often producing unique results.

Inevitably the aircrew and the flights themselves attract attention, but I am glad to see that the other actors in this story also receive the credit that is due to them. The ground crew who serviced the aircraft and sensors were even more in the shadows than the aircrew, but nothing would have happened without their professional and strictly discreet efforts, which in some cases involved keeping venerable systems punching well above their weight and beyond their natural life. On the other hand they also had to master the intricacies of some of the most advanced sensors of the time.

Then there were the interpreters. It may be true that the camera never lies, but the images can often deceive and conceal, as more than one impatient operational commander has learnt to his cost. The artful science of the imagery analyst was absolutely fundamental to these operations. It is a skill that has evolved over many years, keeping pace with the technology of both the collector and the target, to make the most of every pixel while seeing through the veil of ambiguity that nature or the opposition might assemble.

As for security, it could be that these operations were better concealed from our own side than from the opposition. It is true that from the national level in capital cities down to individuals within the operating squadrons, the need to know principle was rigorously applied and to this day has kept the story restricted to a few insiders. On the other hand, there are plenty of incidents that suggest that the other side was aware that reconnaissance flights were taking place. Suspicious Soviet air traffic controllers, rudely finger-waving East German soldiers, messages written in the snow, not to mention aggressive approaches by opposition fighter aircraft, all point that way. What they could not have known was the sheer quantity and quality of information that was being collected.

Looking Down the Corridors is the story of the persistent and imaginative application of aerial reconnaissance to one of the most successful intelligence campaigns of the Cold War.

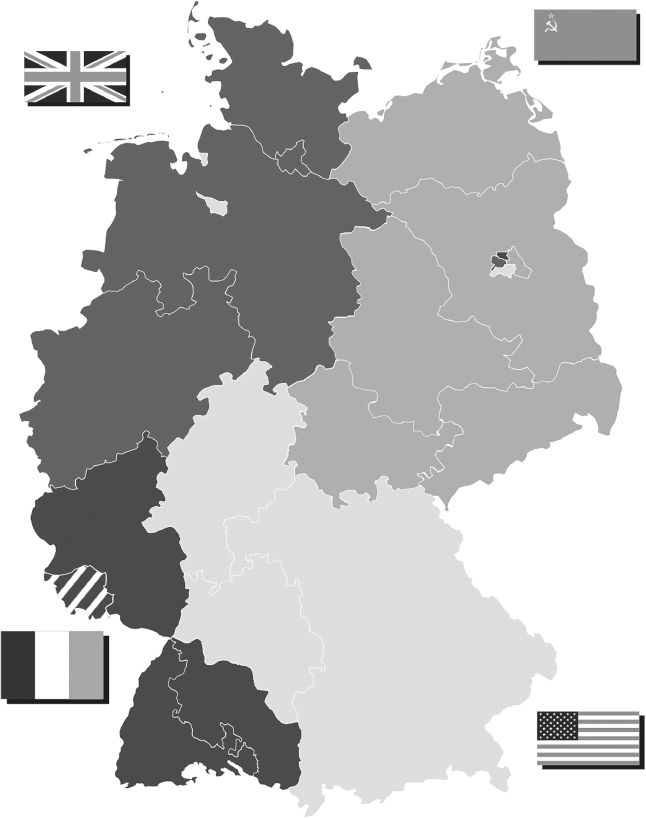

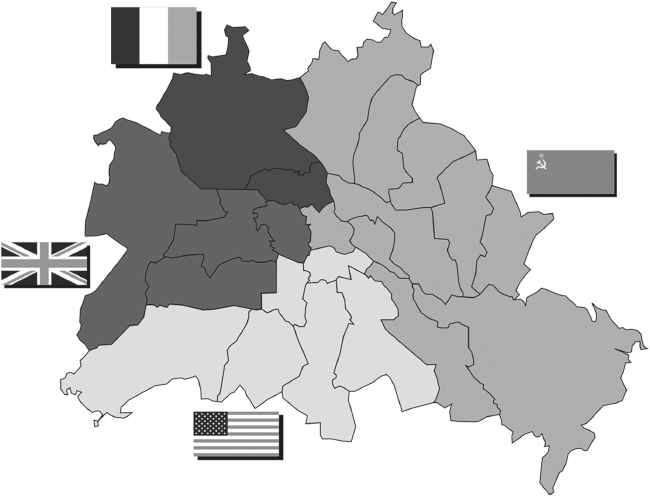

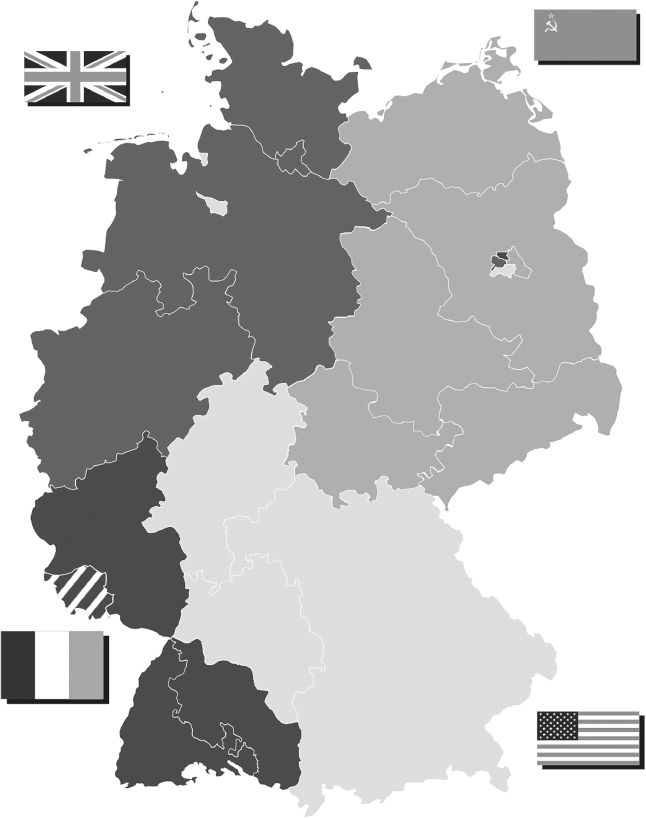

The post-Second World War German Allied occupation zones agreed by the Four Powers in 1945. (Wikimedia Commons)

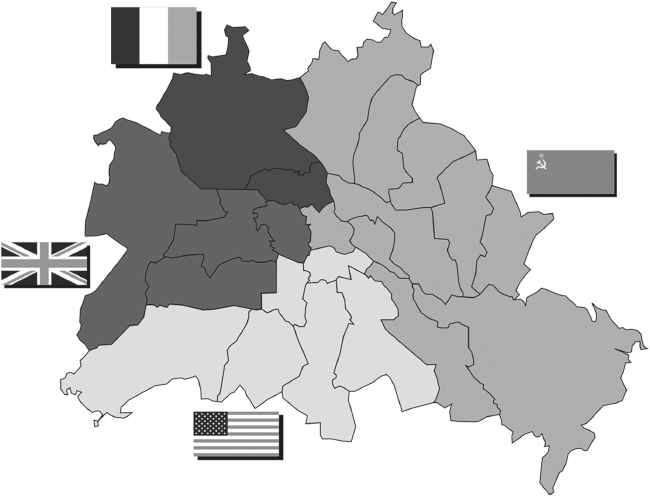

The division of Berlin into the Allied Occupation Sectors created meandering boundaries through and around the city which made policing and protecting them extremely difficult. (Wikimedia Commons)

P ROLOGUE

In July 1968 the Prague Spring crisis in Czechoslovakia was coming to a head. In East Germany at the Soviet garrison of Dallgow-Dberitz, just west of Berlin, the Divisional Commander of 19 Motor Rifle Division had been given orders to prepare his unit to move to an unspecified destination. In the barracks, vehicles had been formed into unit columns ready to move out.

At RAF Gatow in West Berlin, an apparently innocuous Percival Pembroke light transport aircraft took off, bound for RAF Wildenrath in West Germany. However, this was no ordinary Pembroke. Concealed in its fuselage were five powerful reconnaissance cameras. As it passed over Dallgow-Dberitz the camera doors in the belly opened and the scene below was recorded.

On arrival at RAF Wildenrath the film magazines were rapidly removed and transferred to the headquarters complex at Rheindahlen where they were processed and passed to the Army and Royal Air Force photographic interpretation units for analysis. The very high level of activity in the garrison was swiftly reported to local intelligence staffs, the Ministry of Defence in London and select members of the Allied intelligence community.

Next page