Berlin on the Brink

BERLIN

ON THE

BRINK

The Blockade,

the Airlift,

and the

Early Cold War

DANIEL F. HARRINGTON

Copyright 2012 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

16 15 14 13 12 5 4 3 2 1

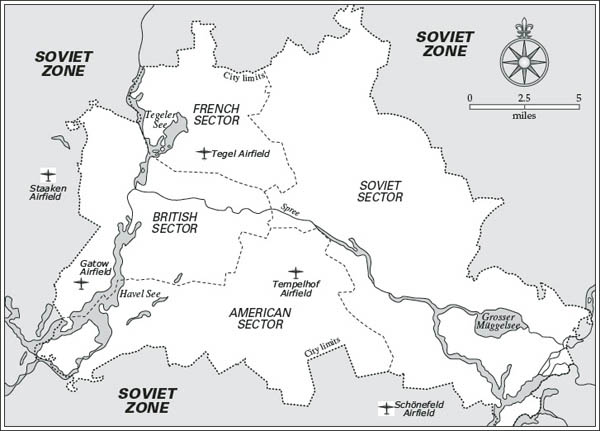

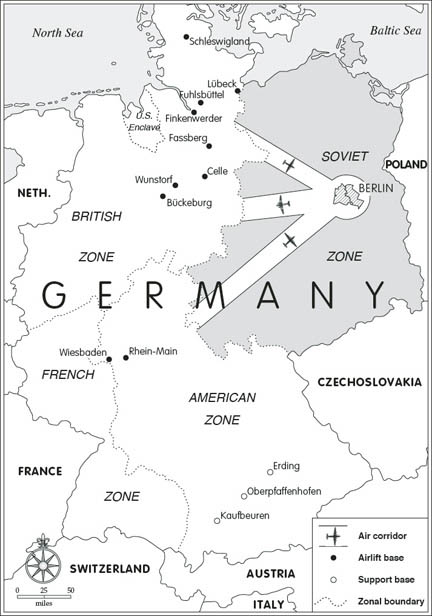

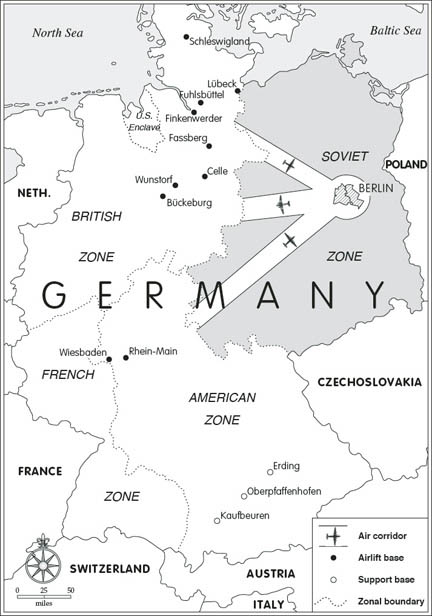

Maps by Richard A. Gilbreath, University of Kentucky Cartography Lab

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Harrington, Daniel F.

Berlin on the brink : the blockade, the airlift, and the early Cold War / Daniel F. Harrington.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-3613-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-3614-1 (ebook)

1. Berlin (Germany)HistoryBlockade, 1948-1949. 2. Cold War. I. Title.

DD881.H318 2012

943'.1550874dc23 2012004169

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

To Sylvia, Elizabeth, and Laura,

who bring light and love

to the corridors of my life

Contents

Occupied Berlin

Germany during the Berlin blockade

Introduction

NO PLACE SYMBOLIZES THE COLD WAR more than Berlin. In July 1945, the wartime Allies met on the outskirts of Adolf Hitlers ruined capital and barely managed to paper over their differences. Three summers later, Berlin brought them to the brink of war. Crises in the late 1950s and early 1960s created a new symbol of their conflictthe Berlin Wallas Soviet and American tanks faced each other at Checkpoint Charlie. The city later acted as a barometer, measuring the change in atmosphere as tensions eased. The 1971 quadripartite agreement ushered in the era of dtente, and the opening of the Wall in November 1989 signified the Cold Wars end.

The tanks at Checkpoint Charlie have only one competitor as an iconic image of Cold War Berlin: a cargo plane flying over the war-ravaged city during the Berlin blockade. From June 1948 to May 1949, the Soviet Union isolated the western half of the city from its normal sources of supply. The other occupying powers, the United States, Great Britain, and France, sustained their sectors by flying in coal, food, and other necessities. For generations of Americans and western Europeans, the contrast between Joseph Stalins ruthless blockade and the Wests humanitarian airlift offered eloquent proof of Arthur Schlesingers contention that Western Cold War policies were the brave and essential response of free men to communist aggression. Westerners still find inspiration in the airlift as the most dramatic mobilization of military technology to save lives in the twentieth century. Claiming parallels between their actions and Harry Trumans, recent presidents have invoked the airlift to bolster support for their policies.

Although an enormous literature exists about Cold War Berlin in general and the blockade in particular, aspects of the crisis remain obscure. One noted historian of the blockade has declared it one of the most ambiguous and least understood events of the Cold War.expand access after 1945. Historians do not explain why Western officials did little to reduce the citys vulnerability as tensions increased in late 1947 and early 1948.

Another question is the airlifts place in Western policy. According to most accounts, officials quickly settled on an airlift as their counter to the blockade. Yet historians also claim that Western leaders at the time believed Berlin could not be supplied by air. In other words, Western governments chose the airlift as their response, expecting it to fail. That does not make sense. What, then, was Western policy, and how did the Western powers expect to prevail against the blockade?

THIS BOOK TRIES TO CLARIFY such issues by examining the Berlin question from its origin in wartime plans for the occupation of Germany through the 1949 meeting of the Council of Foreign Ministers in Paris. Although the blockade and the airlift form the centerpiece of this story, the narrative puts them in a broader context. It examines the origins of the Berlin problem during the Second World War, looks at how East-West cooperation in Berlin and Germany broke down between 1945 and 1948, and then turns to the crisis itself. It covers the diplomatic maneuvering, the evolution of the airlift, and events in the blockaded city. It concludes by describing the foreign ministers meeting in Paris, which ratified the division of Berlin and Germany and established the framework for decades of cold war in Europe.

Diplomatic histories tend to concentrate on the high and the mighty. This account is no exception. At one level, it is a case study of how governments behave during crises. Yet the outcome did not turn solely on what national leaders planned and decided. It depended just as much on the actions of airlift pilots and the residents of Berlin. Only by examining the intertwined topics of national policies, the airlift, and life in Berlin can we understand how this confrontation erupted, evolved, and was resolved.

While drawing on secondary literature, the study rests on research in British, American, and Canadian archives, ranging from Berlin sector records to presidential and prime ministerial files. Postwar Berlin has become too familiar in some ways, encrusted with unexamined assumptions and myths. Stories have come to be accepted as true through constant repetition, when their factual basis is questionable. Memoirs are selective, sometimes misleading, occasionally distorted. I went back to the primary record whenever I could. Here I must add an embarrassing caveat. My lack of fluency in French, German, and Russian means that this is not the definitive account I wish it was. I tried to compensate by drawing on studies of Soviet policy that have appeared in English in the last two decades, and I used a handful of works in French and German. The lack of primary material in these three languages weakens my analysis. I can only hope that my work will encourage others to provide a better-rounded account than I have offered here.

Despite its limitations, my research calls into question existing views of the blockade and its origins. The failure to secure written guarantees of Western access to Berlin seemed the height of folly after 1948, and critics were quick to blame the problem on naive trust in Soviet goodwill on the part of Franklin Roosevelt and his advisers. Yet the plan that left Berlin surrounded by the Soviet zone was a British product, not an American one. And although the belief that the Russians would cooperate did influence wartime plans, other considerations were just as important, such as the expectation that the zones would exist for only a short time, the notion that forces of the Allies would move freely in all zones, and the idea that Western access routes would sustain only the garrisons, not Berlins entire population.

Next page