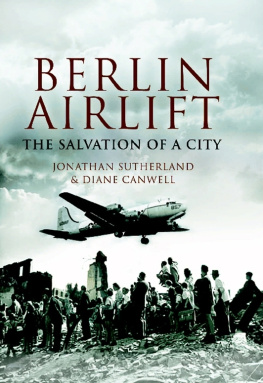

They all remember the air-lift with great pride. Then Berlin was in the centre of the world-interest and the Berliners were convinced that the West really cared for them. The days of the air-lift were hard days, exciting days, terrible days. But those were the days.

George Mikes, Uber Alles: Germany Explored, 1953

Berlin is all about volatility. Its identity is based not on stability but on change. No other city has repeatedly been so powerful, and fallen so low. No other capital has been so hated, so feared, so loved. No other place has been so twisted and torn across centuries of conflict, from religious wars to Cold War, at the hub of Europes ideological struggle.

Rory MacLean, Berlin, 2014

F or Pilot Officer John Curtiss, it was his second flight to Berlin. The first, in January 1945, had been a mission of destruction. As a Bomber Command navigator he had guided his Halifax through the waving crisscross of blinding searchlights to that nights target, an oil refinery on the edge of the city. He had heard the order for the bomb doors to be opened, seen the orange flashes far below and tried not to think of the devastation and sacrifice. Now, in July 1948, just three years after the end of the war, John Curtiss was flying not over but into Berlin and his aircraft was carrying not bombs but food and fuel for a city under siege. He was just one of thousands of American and British servicemen taking part in the Berlin Airlift, the most ambitious relief operation of its kind ever mounted.

Over eleven months, from June 1948 to May 1949, 2.3 million tons of supplies were shifted on 277,500 flights. Average daily deliveries included 4,000 tons of coal, a bulk cargo never before associated with air carriers. A record day had nearly 1,400 aircraft, close on one a minute, landing and taking off in West Berlin, creating a traffic controllers nightmare at a time when computer technology was still in its infancy. But just about every statistic of the Airlift broke a record of some sort. For those who took part, the sense of achieving something remarkable was to stay with them for the rest of their lives.

John Higgins was an eighteen-year-old dispatch rider when the Airlift was mounted.

Of my 22 years of service I was in Cyprus, Kenya and other trouble spots it was Berlin where I grew up. In eighteen months I changed from a young English hooligan. For the first time I saw the world as a decent human being should see the world.

Fifty years on, John took part in an anniversary veterans march in Berlin.

All the schoolchildren were giving us flowers. Then we went up the steps to take our seats and there was an old lady with tears running down her face, just saying Danke, danke. I gave her my flower. And I couldnt talk.

John Curtiss, by then a retired air vice marshal, was also at the veterans reunion. He was approached by a middle-aged man who was eager to show his gratitude. If it wasnt for you and those like you, I wouldnt be here. My parents swore that if the communists took over, they would never have children.

*

Berlin was a divided city in a divided country in a divided continent. It was not supposed to be like that. Victory over Germany promised a fresh start, a concerted Allied effort to secure a lasting peace in Europe. But it was soon clear that the much-vaunted unity of America, Britain and Russia was based on little more than a joint interest in defeating Nazism. Once the enemy was vanquished, the thin veneer of military and political camaraderie peeled away.

For the more sceptical or more clear-sighted observers, the fragility of the alliance was apparent even while the war was raging. An inter-Allied dialogue on post-war Germany started in mid-1943 when the defeat of the Third Reich, though some time in the hazy future, was judged to be inevitable. In October, a deceptively constructive meeting of Allied foreign ministers in Moscow (Cordell Hull for the United States, Anthony Eden for Britain and Vyacheslav Molotov for the Soviet Union) led to the creation of a three-power European Advisory Commission (EAC) to be based in London. America and Russia were represented on the Commission by their respective ambassadors, John Winant and Fedor Gusev, while the British case was put by Sir William Strang, a long-time government adviser on international affairs.

Their brief was prescribed by decisions already made at top level. That Germany should submit to unconditional surrender, affirmed by President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill in January 1943 at their Casablanca conference and subsequently endorsed by Joseph Stalin, was justified as a means of forestalling any inclination, east or west, to negotiate a separate peace. The absence of any flexibility in bringing the war to an end carried with it the message that a defeated Germany would have no say in managing its internal affairs. Unconditional surrender equated with the surrender of sovereignty. It would be up to the Allies to tell the Germans how to run their lives.

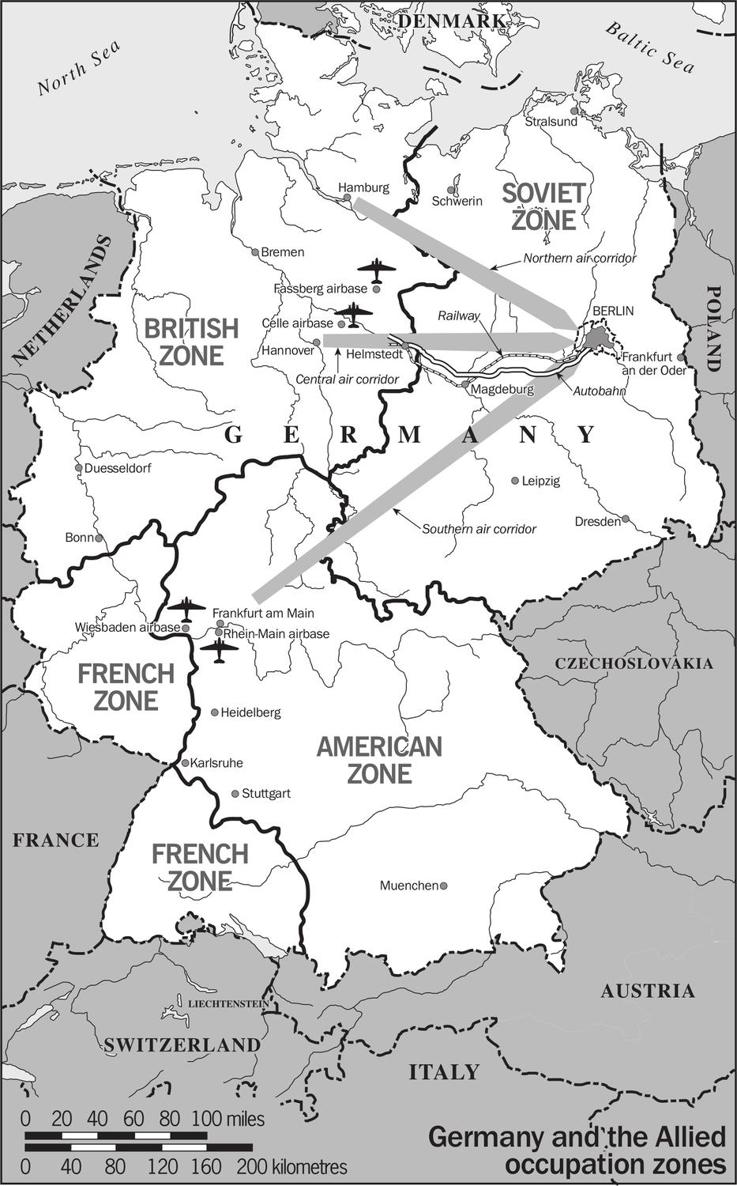

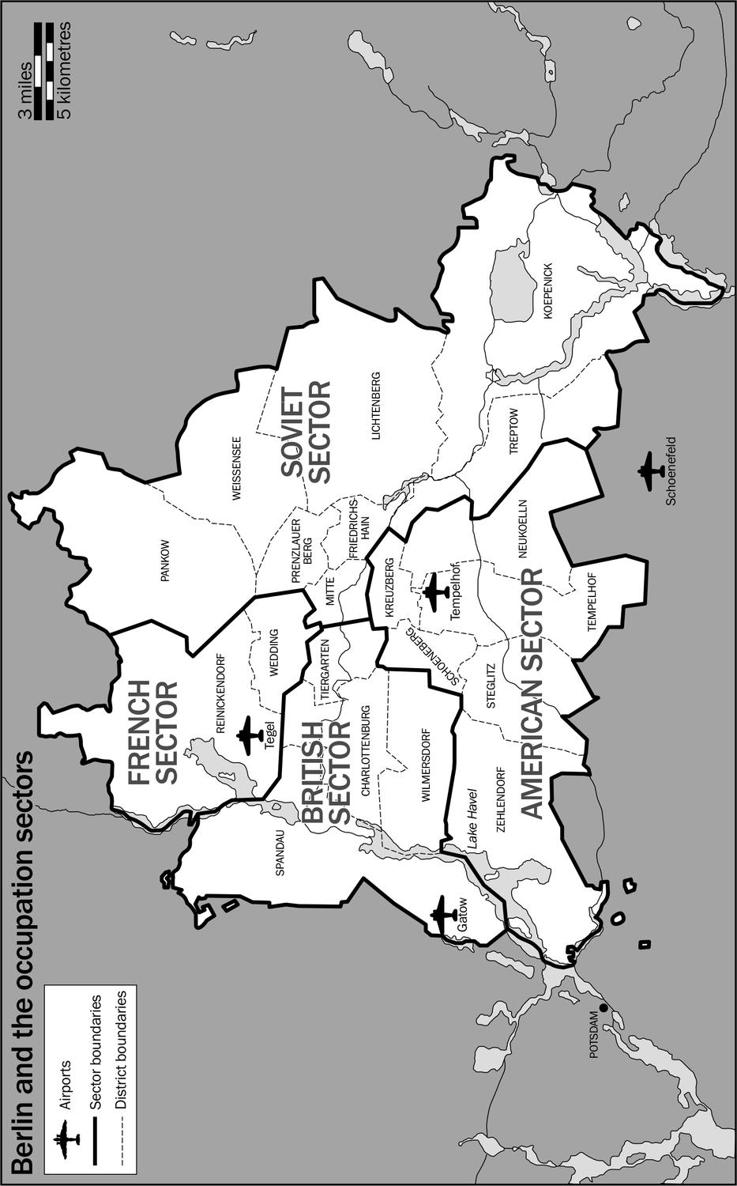

But this was to assume that the Big Three could agree on what they wanted for Germany. At no point was this seriously in prospect. The best that the EAC could come up with was a formula for partitioning of Germany into occupation zones under military government with no conditions on the length or terms of occupation. Matters of joint interest were to be settled by an Allied Control Council comprising the commanders-in-chief with their deputies. Berlin was to have its own Interallied Governing Authority (Kommandatura).

These arrangements, so neat and tidy on paper, came with a list of open-ended questions, not least the fixing of the lines of demarcation for the occupation and access to Berlin, which was likely to be in the Soviet zone. The assumption by the western Allies was of free and open transit to the German capital. But the Russians refused to be tied down. Strang noted a disturbing tendency for his EAC Soviet counterpart, a grim and rather wooden person to haggle over insignificant details. In putting this down to bloody-mindedness he failed to recognise the Soviet tactic of playing for time while the advancing Red Army tightened its grip on the territories it occupied.

With his innate distrust of communism in general and of Stalin in particular, Churchill had a clearer idea of what was going on. But priding himself as a realist, he acknowledged Stalins obsession with security, his own and that of his country. The Soviet leaders resolve to surround Russia with states directly controlled by or submissive to the Kremlin was on a par with his need to be surrounded by underlings of unquestionable loyalty. Given Russias sacrifice in defeating Nazism, with close on 9 million military and 17 million civilian deaths, Stalin expected more than a share of Germany and was in prime position to get it. Hence Churchills infamous percentages offer to Stalin exchanging Russian control of Rumania and Bulgaria for British ascendancy in Greece, leaving Hungary and Yugoslavia to be split evenly.

This did not go down well in Washington where President Roosevelt, my very good friend as Churchill liked to call him, was of another school of diplomacy. Having served his political apprenticeship in the Great War, he was imbued with the idealism of Woodrow Wilson. The failure of the League of Nations, Wilsons brainchild, only made Roosevelt more determined to create a new world order based on mutual trust. This was far distant from Churchills credo, practical or cynical according to taste, that the only way to keep the peace was to engineer a balance of power between leading nations, enabling each to satisfy its territorial ambitions without any one country becoming strong enough to overwhelm the others.