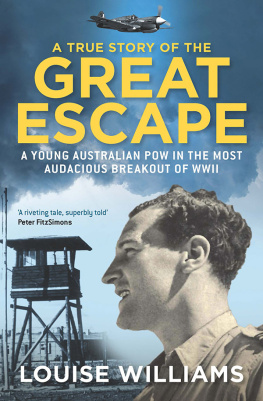

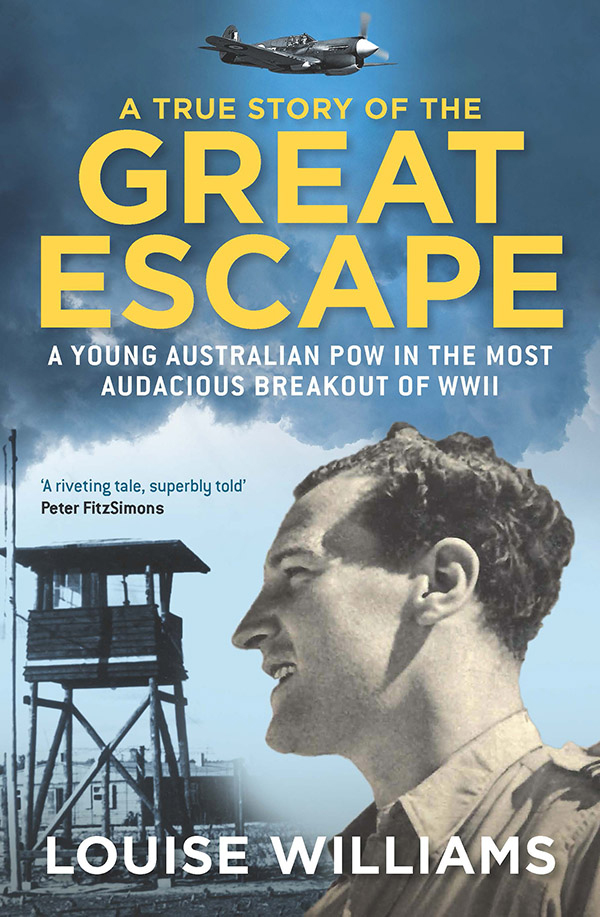

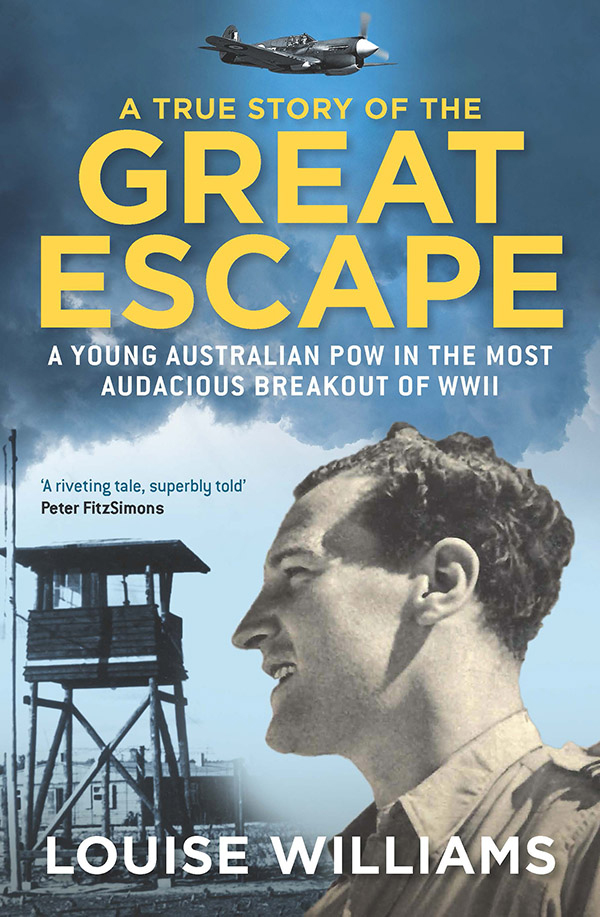

This excellent book features the lives and times of John Williams DFC and Rusty Kierath who were courageous and distinguished Australian fighter pilots, determined and innovative prisoners of war and daring great escapers. Louise Williams tells their stories and reveals the impact on their families with great empathy, sensitivity and skill.

Air Chief Marshal Sir Angus Houston AK, AFC (Retd)

Its a wonderful book and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Its the story of a Great Escaper, but its so much more than that. Its an intimate portrait of a man who rose to every challenge that appeared before him, but also the tale of Louise Williams quest to understand the uncle she never met. The characters are beautifully sketched, making this a totally absorbing story, written with empathy and insight.

Professor Jonathan F. Vance, author of A Gallant Company, The Men of the Great Escape

Louise Williams warm, wise, meticulously researched book traces the personal odysseys of two fine young Australians; taking them from the playing fields of Sydneys Shore School and the surf at Manly Beach, to their service as fighter pilots in the skies of North Africa, and on to their incarceration as POWs at the notorious Stalag Luft III. This book also offers fresh insights into the Great Escape of March 1944, and its chilling aftermath, and has much to contribute on the subjects of remembrance, forgiveness and reconciliation.

Peter Devitt, Curator, RAF Museum, London

Louise Williams is an award-winning writer, journalist and editor, and niece of John Williams. She has recreated Johns story from family memories, letters, declassified documents, oral histories and interviews with survivors of the Great Escape.

She spent more than a decade as a foreign correspondent for Fairfax newspapers (the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, Melbourne) based in Manila, Bangkok and Jakarta. Louise has written or contributed to a number of books and was the recipient of an Australia Council Asia Pacific Writers Fellowship. Louise won a Walkley Award for Excellence in Journalism and the Citibank Pan Asia Journalism Award (in conjunction with Columbia University) for her work as a foreign correspondent. Louise is also a Research Associate of the Australian Centre for Independent Journalism (ACIJ) at the University of Technology.

Every effort has been made to trace the holders of copyright material. If you have any information concerning copyright material in this book please contact the publishers at the address below.

First published in 2015

Copyright Louise Williams 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74331 389 3

eISBN 978 1 92526 668 9

Internal design by Phil Campbell

Typeset by Post Pre-press Group

Cover design: Philip Campbell Design

Cover images: Hulton Archive/Getty Images/Williams family collection

For our dear friend Michal Holy,

and in loving memory of John Willy Williams and Reginald Rusty Kierath

It is a melancholy fact that escape is much harder in real life than in the movies, where only the heavy and the second lead are killed. This time, after huge success, death came to some heroes. Later it caught up with some villains.

Paul Brickhill, RAAF officer, Stalag Luft III POW and author of The Great Escape

CONTENTS

I had never really expected to stand on the exact spot where the secret escape tunnel they called Harry came up outside the wire of that infamous German POW camp, Stalag Luft III. Nor did I imagine I would ever have the opportunity to retrace the footsteps of my uncle, John, escapee number 31, and to put his story back together piece by piece.

I was born in 1961. My parents had lived through World War II and my grandparents had lived through two world wars. As family stories go, its fair to say I grew up with John and his apparently extraordinary wartime experiences. However, despite the release of the movie, The Great Escape, and its popularity throughout the 1960s, the Hollywood version of the escape was so thoroughly Americanised that the real story remained distant, and largely inaccessible to us post-war kids, born into optimism and rapidly growing prosperity.

Europe was a very long way away from Australias beaches. Certainly, we all embraced Johns pre-war passion for surfing and his particular love of the southern corner of Manly Beach, a little pocket of paradise so sheltered and warm that it was always swimmable. At least thats what my dad claimed. My father, Owen, the tail-ender of the five Williams kids, and ten years younger than John, challenged himself, and us, to surf at Manly without a wetsuit all year round. It was much easier to relate to the history of surfing, and Johns brief role as an early pioneer on a wooden board and as a champion surf-lifesaver at the local Manly club, than to distant former European and north African theatres of war.

And, to be honest, family history isnt for the young. When you are so busy planning ahead, theres never enough time to look back. We were so interested in where we were going, we didnt really pay much attention to where we might have come from.

By the 1970s war stories were fast going out of fashion anyway. Popular opposition to the Vietnam War, and to armed conflict in general, began to sour military homecomings. We began to re-examine the rights and wrongs of war from the safety of the affluent Australian suburbs, as though violence as a means to any end was a simplistic, moral issue; all bristling aggression, expansionism and military adventurism and never, in itself, an anguished response of last resort.

In the 1980s my father, mother and brothers travelled to Europe, then a major undertaking for a family of modest financial means. My dad stood at inquiry counters in London seeking information about Johns war record to no avail. He hit one dead end after another.

The end of World War II had triggered some radical border realignments across Europe. Not only was Stalag Luft III now in Poland but Poland had fallen under the brutal Cold War purview of the Soviet Union and so was then firmly locked behind the Iron Curtain, the ruins of the camp left to the vagaries of nature.

And, the daily demands of life intervened. I became a foreign correspondent, a role that, ironically, enabled me to tell many other peoples dramatic stories, featuring so many new and terrible types of conflict and cruelty that conventional warfare and the rules of engagement of World War IIat least as they were supposed to regulate wars to limit brutalityseemed almost naive.

Next page