Contents

Guide

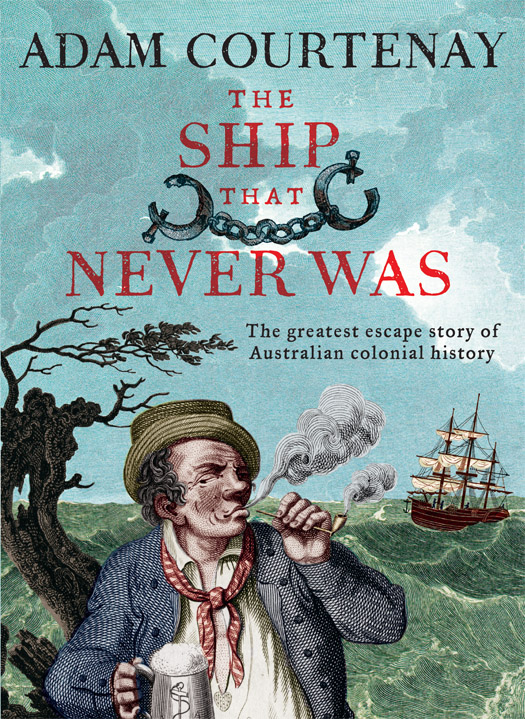

ADAM COURTENAY is a Sydney-based writer and journalist who has had a long career in the UK and Australia, writing for papers such as the FinancialTimes, the Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, the Australian Financial Review and the UK Sunday Times. The son of Bryce Courtenay, he is the author of two previous books, Blood Rubber and Amazon Men.

| The ABC Wave device is a trademark of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and is used under licence by HarperCollinsPublishers Australia. |

First published in 2018

by HarperCollinsPublishers Australia Pty Limited

ABN 36 009 913 517

harpercollins.com.au

Copyright Adam Courtenay, 2018

Adam Courtenay asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

This work is copyright. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied, scanned, stored in a retrieval system, recorded, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

HarperCollinsPublishers

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

Unit D1, 63 Apollo Drive, Rosedale 0632, Auckland, New Zealand

A 75, Sector 57, Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201 301, India

1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF, United Kingdom

Bay Adelaide Centre, East Tower, 22 Adelaide Street West, 41st Floor, Toronto, Ontario, M5H 4E3, Canada

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007, USA

ISBN: 978 0 7333 3857 1 (paperback)

ISBN: 978 1 4607 0884 2 (ebook)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia:

Picture credits: 217 Public Domain/Smithsonian Libraries; 304 Public Domain/State Library of New South Wales

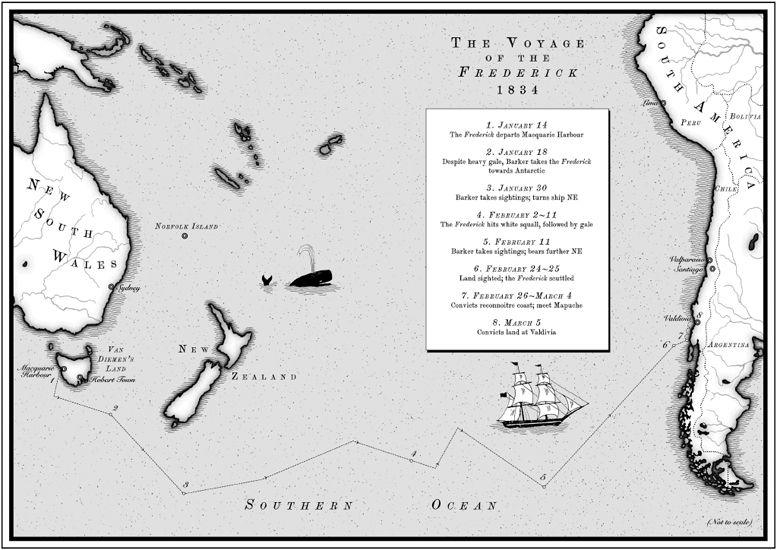

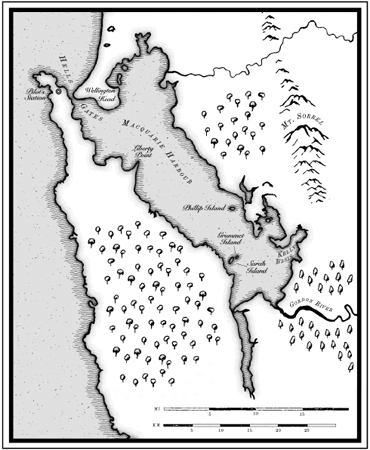

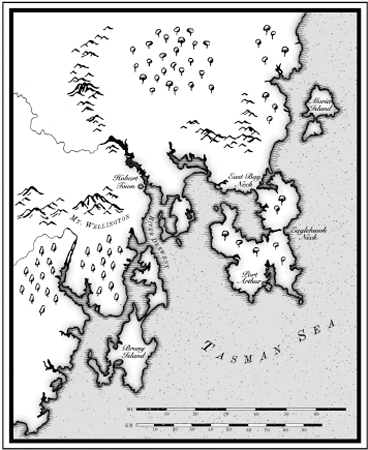

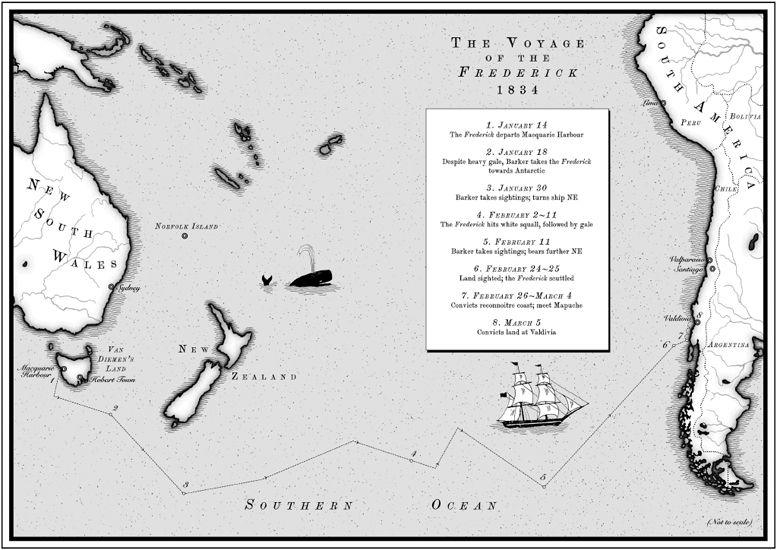

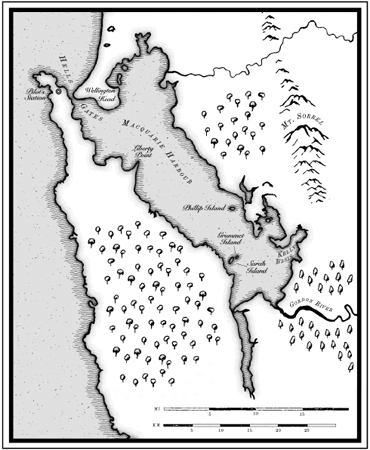

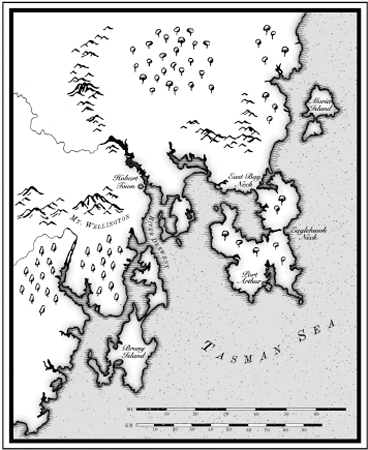

Maps by Clare OFlynn/Little Moon Studio

Cover design by Peter Long

Cover images: Man courtesy The Lewis Walpole Library,Yale University; background illustration Ceyx and Alcyone (1769) courtesy National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

To Damon, who never had the chance.

A man who has been all his life fighting against law, who has been always controlled but never tamed by law, is interesting, though inconvenient as is a tiger.

Anthony Trollope

Australia, 1873

MACQUAIRE HARBOUR

HOBART

T HEY WERE DESPERATE for land.

As he looked out on the blank blue swells of the Pacific Ocean, James Porter feared he and his makeshift crew had left too much to fate. They had trusted in a navigator who had never been to sea. They had taken a ship that had never sailed before. Shed been built to hug coastlines and harness coastal breezes, not to sail the length of the Southern Ocean. Too much had been asked of her.

Not long into their passage, the men had realised their mistake in not keeping enough rations. There was now hardly anything for themselves, each man choking down a tiny portion of hard biscuit and dried beef each night.

Porter never tired of how the ship slotted into the wind. Even now, cracked and leaking below, she made excellent progress astride a solid nor-easter. And yet the fear remained. No matter how hard the men worked at the pumps, the green Huon pine planks might give at any moment. Their situation was both precarious and perilous. And this had been their lot for several weeks a crew desperately looking for a hint of land on the horizon, the never-ending clank of a pump beating out a doleful time, the yearning in their stomachs growing more acute as one day melded into another.

They had a natural leader, whom Porter had always respected, but was he the right man to be their captain? He had learnt his navigation without setting foot on a boat. Did he actually know where they were, or was he bluffing while he tried to work it out?

Six of the ten-man crew grew sick every time a serious wind blew and the ship started to roll, and only four of them really knew what they were doing. Four men to sail, keep watch, work the sails and bail the water out. In truth, they needed at least a dozen men to keep the little brig going. They needed three times as much food in case the navigation went awry and they were further away from land than theyd been led to believe.

They needed rest. More than anything, Porter and his crewmates needed rest. This wasnt unusual for renegades and mutineers, but not even Porter had experienced such desperation when sailing before. Hed worked many ships but never with such a skeleton crew. Sailing wasnt a lark when you needed to do four jobs at once.

Still, theyd already survived furious ice-cold winds and mountainous waves. In their urgency to escape, they had travelled far to the south, practically into Antarctic waters. It had been almost unbearably cold, and Porter thanked the fact that at least they were sailing in summer. They wouldnt have survived the same route in winter.

But if their navigator had taken them too far south, had he adjusted the course so they were now far enough to the north? If they struck land, where would that be?

Part of Porter also silently thanked their great shipbuilder. Although hed warned Porter that this ship couldnt make it across the Southern Ocean, Porter had heard his other boasts. He had the sight, hed say. He knew the lines. He cut the sheer. Hed been schooled in the Boston shipyards, where the worlds fastest boats scoured the seas for the great sperm whale. The Americans had taught him how to craft a line that took the boat through the water with barely a ripple. Yes, this ship was cracking up now, but Porter still counted on the shipbuilder being right about his manufacturing prowess and wrong about their chances of survival.

Just before sunset, one of the men stared to the east, put his hands to his eyes and called for a spyglass. Land ho, land on the starboard bow! he shouted.

When the crew looked eastwards, everybody saw the dark silhouette in the far distance.

A bank of cloud nothing more, the navigator said. By his reckoning, they were still five hundred miles from land, at least three days sailing.

For the first time, he was countermanded. The sails were shortened and the brig was made to hove to, coming to a halt, bobbing on the water. Had land not been sighted late in the afternoon, they could have run aground in the darkness.

The crew kept a lookout all night and by morning it was plain. After six weeks of nothing but waves, wind, squalls and driving rain, a glorious green coastline materialised.

The men jumped around, cheering and hooting it looked like salvation was at hand. But their elation could not be sustained. The ship was mocking their joy, getting heavier in the water. A wooden coffin. They were floating on borrowed time.

T HE TRANSPORT SHIP Asia lay quietly in the DEntrecasteaux Channel overnight, its sweltering human cargo not sure whether the following day should be celebrated or dreaded. Come the morning tide, the Asias crew would have to keep a close eye on the channels fractious currents before making a clean run for Hobart Town.

Next page