Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

PARADISE IN CHAINS

By the Same Author

A HIGHER FORM OF KILLING:

Six Weeks in World War I That Forever Changed the Nature of Warfare

A PIRATE OF EXQUISITE MIND:

Explorer, Naturalist, and Buccaneer: The Life of William Dampier

BEFORE THE FALLOUT:

From Marie Curie to Hiroshima

LUSITANIA:

An Epic Tragedy

THE BOXER REBELLION:

The Dramatic Story of Chinas War on Foreigners That Shook the World in the Summer of 1900

A FIRST-RATE TRAGEDY:

Robert Falcon Scott and the Race to the South Pole

THE ROAD TO CULLODEN MOOR:

Bonnie Prince Charlie and the 1745 Rebellion

THE DARK DEFILE:

Britains Catastrophic Invasion of Afghanistan, 18381842

CLEOPATRA AND ANTONY:

Power, Love, and Politics in the Ancient World

TAJ MAHAL:

Passion and Genius at the Heart of the Moghul Empire

CONTENTS

On July 2, 1792, the London Chronicle reported the arrival of one of King George IIIs warships at Portsmouth on Englands south coast:

News from Botany Bay from His Majestys ship, the Gorgon . The infant colony is in greatest distress being in want of every necessity of life and by no means in that fertile state represented

The following were [among] passengers on the Gorgon . Captain W. Tench Captain Edwards of the Pandora , upwards of a hundred men, women and children of the Marine Corps, ten mutineers from the Bounty and several convicts that made their escape from [Botany] Bay to Batavia in an open boat though the distance is not less than 1,000 leagues

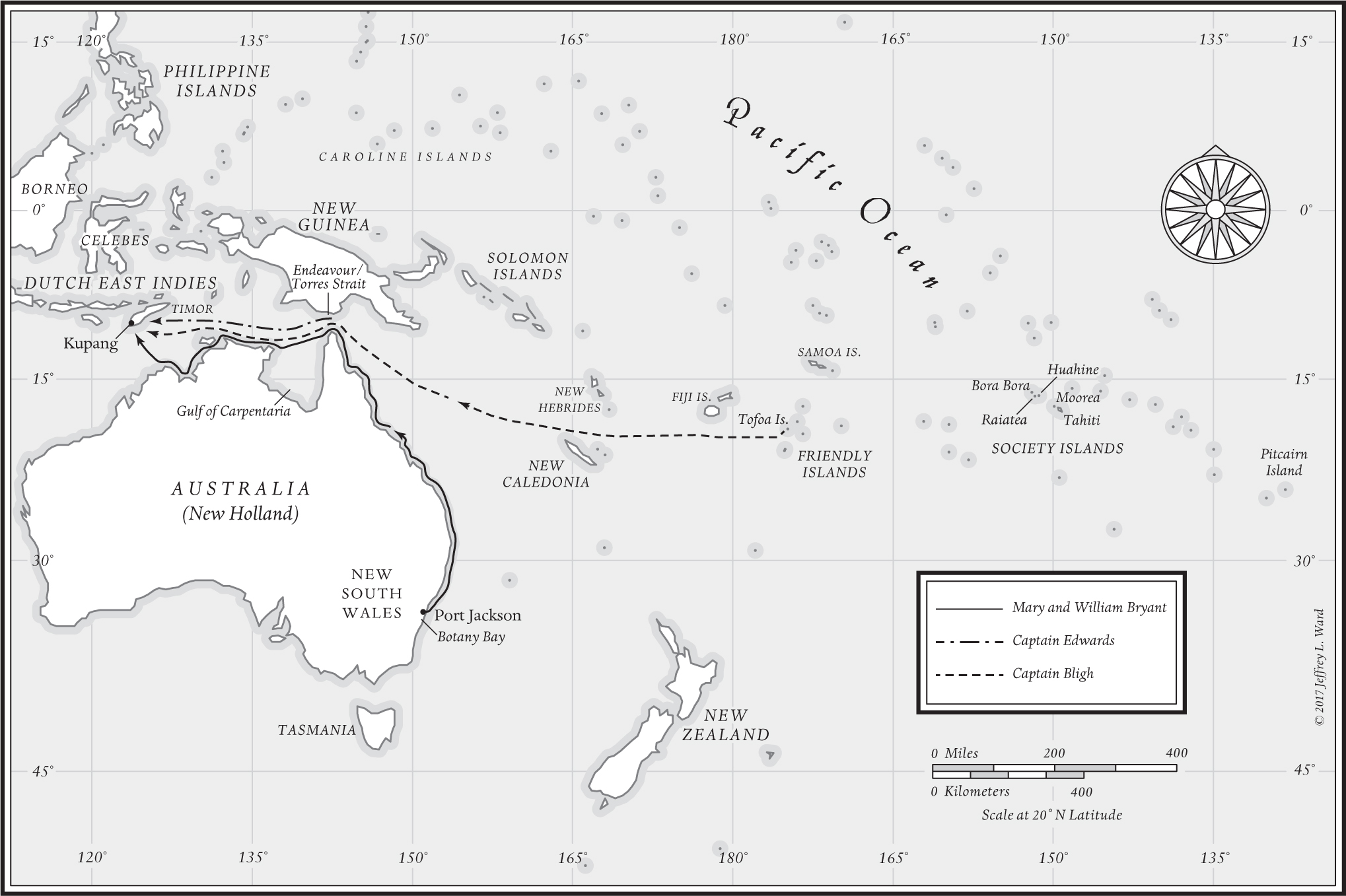

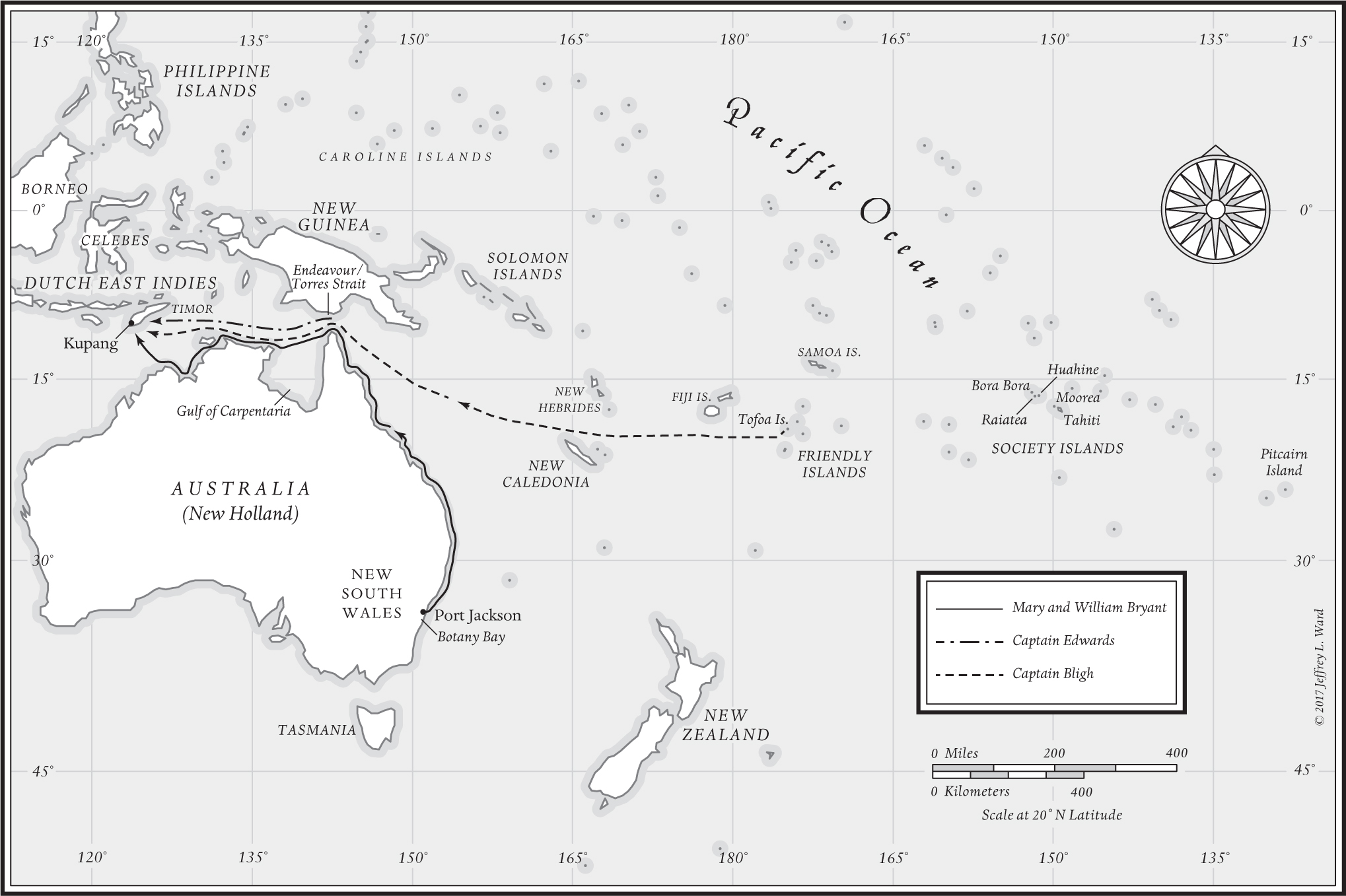

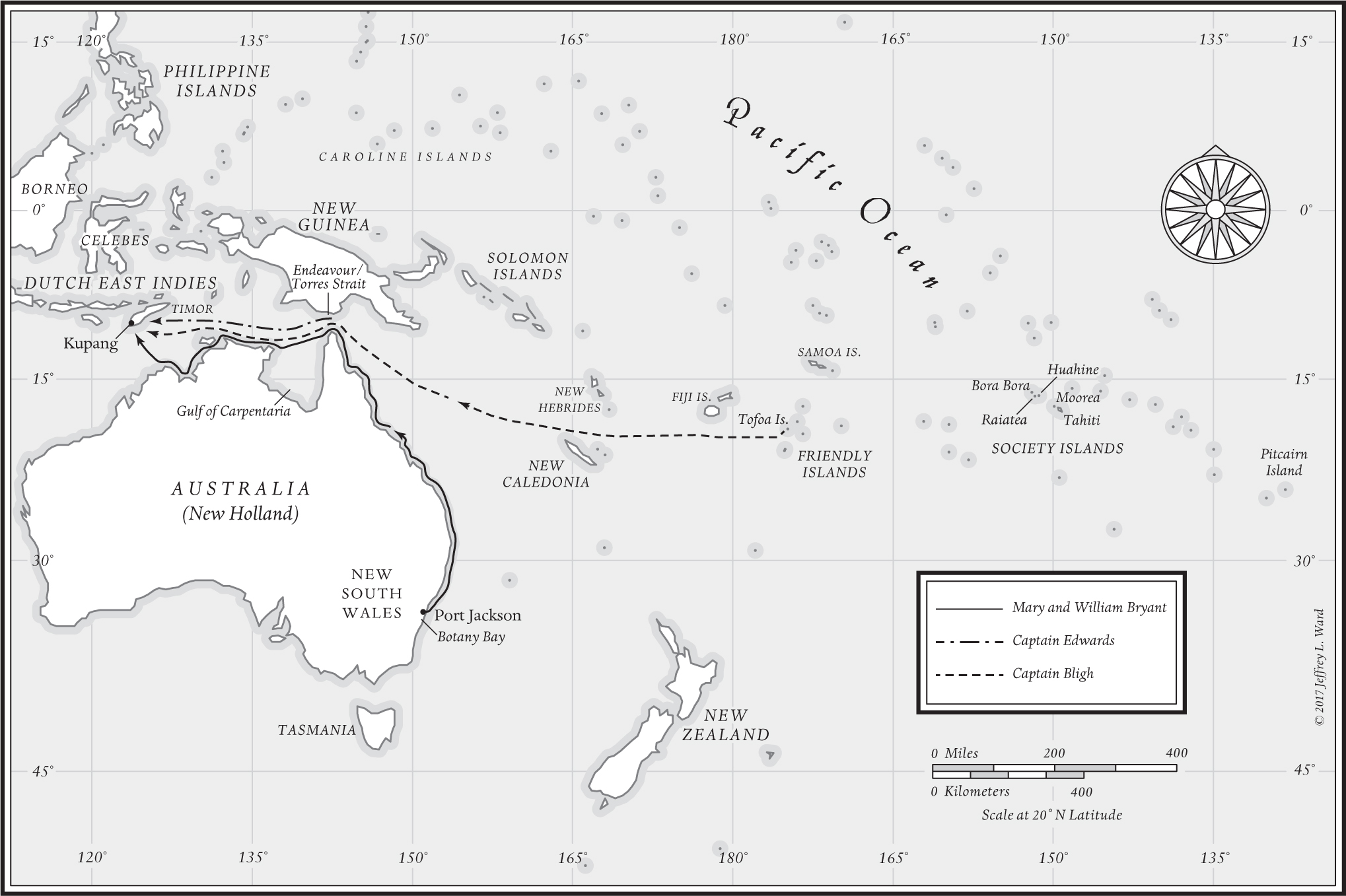

As well as informing its readers of the precarious state of the convict colony founded four years before, this short account also brought together three of the greatest and most dramatic stories of survival at sea. The mutineers were some of those from the Bounty who, after they had put William Bligh over the side with members of his loyal crew to make his celebrated 3,600-nautical-mile, forty-seven-day, open-boat journey to Kupang on Timor, had returned to Tahiti and remained there when Fletcher Christian and the hard core of the mutineers headed for Pitcairn Island.

Captain Edward Edwards, dispatched aboard the Pandora to hunt down the mutineers, had seized them on Tahiti and imprisoned them in harsh conditions in a dark roundhouse on deck that had become known, perhaps predictably, as Pandoras Box. When the Pandora was wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef in August 1791, Edwards and the other survivors made a sixteen-day, 1,200-nautical-mile journey in four open boats to Kupang.

The convicts had made their escape from the penal colony in March 1791. They includedand some said were led bya woman, Mary Bryant, ne Broad. Their open-boat journey of 3,254 nautical miles from Port Jackson, modern-day Sydney, again to Kupang had taken sixty-nine days. Here, in bitter irony, Captain Edwards had arrested them and shipped them home with the mutineers on the Gorgon to face trial. Captain Watkin Tenchreferred to by the London Chronicle was an officer who, with many other marines, was returning from service as one of the initial guards of the penal colony established in 1788. By coincidence, they found themselves aboard the Gorgon with the escaped convicts of whose fate they had until then been ignorant.

The ideas behind the penal settlement and the Bounty s breadfruit voyage to Tahiti had a common origin: Britains attempts to exploit its discoveries made in the Pacific in the third quarter of the eighteenth century by Captain James Cook and others. At one stage they had been planned as a single venturean idea only formally abandoned a week before the convict fleets departure. The two stories would become further intertwined when, in 1805, Captain Bligh was appointed governor of the penal colony where in 1808 he would again suffer a mutiny. A verse circulating in Sydney would ask:

Oh Mores! Is there

No Christian in New South Wales to put

A stop to the Tyranny of the Governor.

The impetus for British attempts to exploit these discoveries was the American War of Independence and the subsequent loss of the American colonies. Britain no longer had priority in its trade with its former colonies, compelling it to seek new markets. A particular problem was finding a source of sustaining cheap food for the slaves on the sugar plantations of the British West Indies, to which breadfruit from the Pacific, which the Bounty was sent to obtain, was believed to be the solution. The British government had also been accustomed to transport to the American colonies prisoners convicted of crimes not considered to merit death but too serious to allow them to return to Britains streets. After exhausting other possibilities, the authorities turned to Botany Bay in New South Wales as a destination, which also offered opportunities for trade and use as a staging post for British merchantmen in the Pacific.

These decisions had a profound impact on the regions people. Earlier British encounters with them in the Pacific, and in Tahiti in particular, had already significantly contributed to the discussion of the noble savage and whether a society based on mans inherent moral qualities had advantages over those ruled by laws imposed by religious and social hierarchies. These debates, and descriptions of the undoubted beauty and charm of the Pacific islands, gave a not entirely accurate and highly romantic view of them as a Utopian paradise, later sustained by the Romantic poets and later still enhanced by Paul Gauguins paintings.

The story of the four decades between the first arrival of the British in Tahiti in 1767 and the arrival of William Bligh in New South Wales as governor is as much one of outstanding characterssometimes heroic, sometimes flawed, and sometimes somewhere in betweenas of ideas and of clashes between cultures and societies. At least as much as Cook and Bligh, the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks stands out. He accompanied Cook on his first voyage, enjoying the amorous favors of Tahitis beautiful women, and searched so hard for botanical specimens that Cook named Botany Bay after his and his associates efforts there. For forty-two years he was president of the Royal Society and he was the key figure behind the eventual choice of Botany Bay as the destination to which British convicts should be transported, behind Blighs breadfruit expedition andsixteen years after the Bounty mutinyBlighs appointment as governor of New South Wales.

Another key figure was Captain Arthur Phillip, the phlegmatic son of a poor German immigrant to Britain, who became a naval officer, spied for Britain against the French, and then served as the commander of the first convict fleet and, following its arrival in 1788, as the first governor of the penal colony. There he displayed remarkable even-handedness in his treatment of guards and prisoners and attempted, if not always successfully, to maintain good relations with the local Aboriginals.