Thank you for downloading this Atria Books eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Atria Books and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

We hope you enjoyed reading this Atria Books eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Atria Books and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

To my father, Tom Franklin, who from an early age taught me the value of a well-placed comma, a properly tended Japanese garden and a devilish sense of humor, and who has always exemplified the power of positive thinking

C HAPTER 1

The Sharkers

H is name was Salvador and he arrived with bloody feet, said he was looking for workanything to startbut to those who saw the newcomer arrive, he looked like a man on the run.

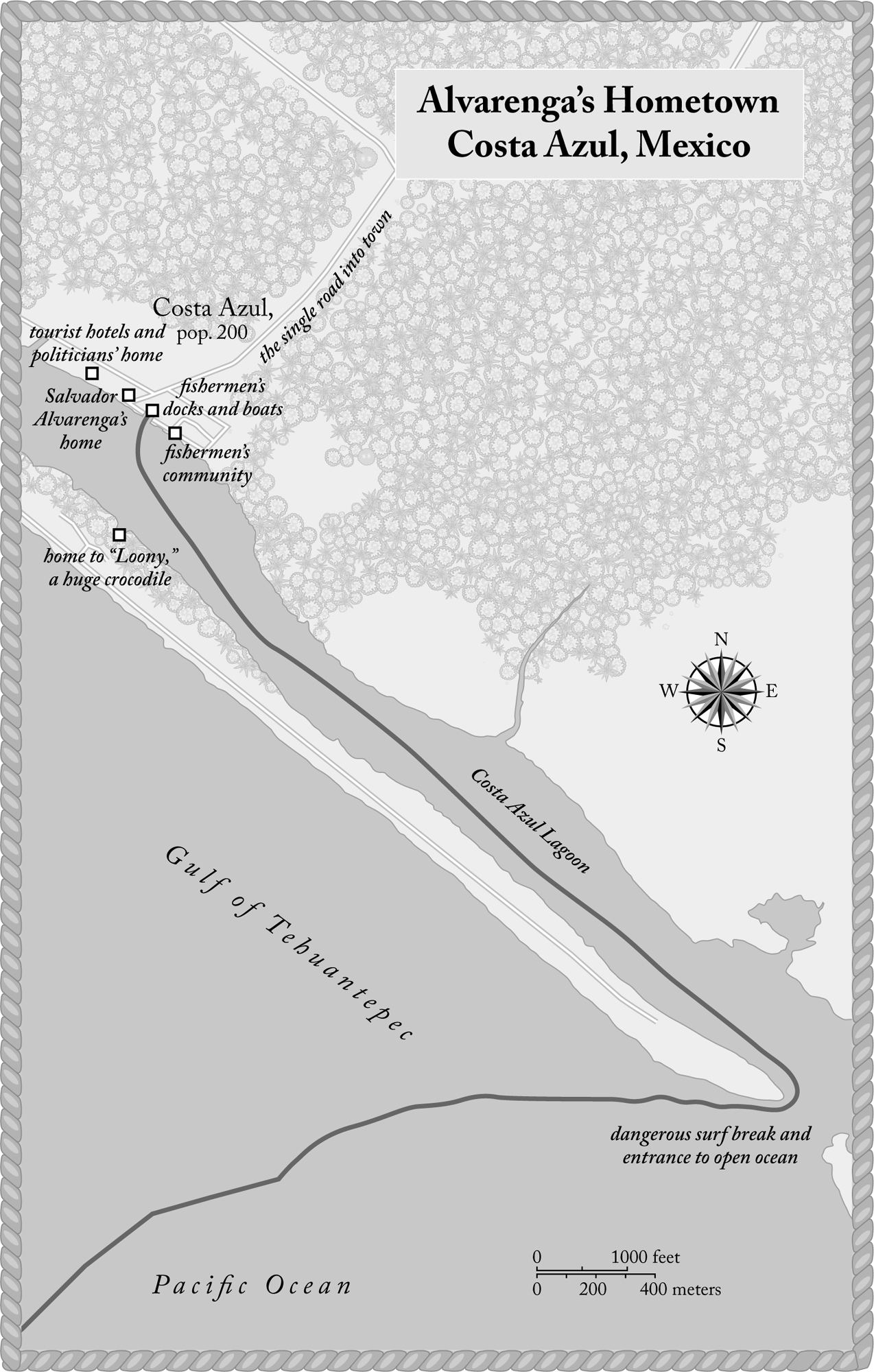

Salvador Alvarenga had walked on rocks for six full days along the Mexican coastline to reach the beach village of Costa Azul. He carried only a small backpack and his clothes were worn. From the moment he entered Costa Azul in the fall of 2008, he felt a deep sense of relief. The mangrove swamps, nearby cornfields, crashing ocean and protected lagoon reminded him of his home in El Salvador, but here no one wanted to kill him. Only a few hundred people lived in the beachside community, though it was densely populated by flocks of migrating birds, many making the 2,000-mile annual journey south from California. Thousands of sea turtles embarked from coastal hatcheries to breed and migratesome making the 12,000-mile swim across the Pacific Ocean to China. The town was half ecotourism paradise, half lawless Wild Westideal cover for a man trying to escape his past and embark on a new life.

Quick with a smile and a helping hand, the round-faced, light-skinned Alvarenga arrived without a visa or working papers, so he pretended to be Mexican. He vigorously defended the lie if anyone questioned his story. Once, when Mexican policemen stopped him and suggested he was a foreigner, Alvarenga broke out with a stanza from the Mexican national anthem.

War, war without truce against who would attempt

To blemish the honor of the fatherland!

War, war! The patriotic banners

Saturated in waves of blood.

Alvarenga had a terrible singing voice made worse by an overdose of confidence. His rendition was off-key and overflowing with nationalistic pride. Convinced by the enthusiasm of his off-the-cuff performance, the police released him.

Costa Azul is a lost corner of Chiapas, Mexicos poorest state and a region where emigrants tend not to stop as they continue on the long trek north to the United States. Few arrivals see much of an economic salvation in the tattered local economy. But the thirty-year-old Alvarenga wasnt looking at landhis eyes were focused on the Pacific Ocean and had been since he was eleven years old and had run away from school to live at the beach with friends. Costa Azul would serve not as home but as home base. He would launch seaward for multiday ocean journeys to the richest remaining fishing grounds along Mexicos plundered coastal ecosystems.

Insulated from the fury of the Pacific Ocean by a miles-long island that creates a natural lagoon, and surrounded by tangled mangrove forests untouched by loggers, thousands of fish inhabit this postcard-perfect lagoon, discovering only too late their fatal error when speared alive on the knife-sharp bill of a blue heron or crushed in the jaws of a crocodile. Like the migrating birds, Alvarenga was attracted to the protected lagoon and its unending supply of easy-to-catch fish. From afar, it gleamed like a refuge. While vicious storms roared offshore, sometimes lasting for weeks, the mangrove jungles absorbed and sheltered this small community. Like the eye of a hurricane, Costa Azuls beauty had an eerie ability to disguise imminent danger.

Going out to sea might seem simple but it is a monster you must face, explains a colleague of Alvarenga known as El Hombre Lobo (The Wolfman). If you are going to face the sea you have to be ready for all it can toss at you, including the wind, a storm or a big animal that might eat youall those dangers. People go out for these little seaside trips, that is not the ocean. The ocean is out there past 120 kilometers [70 miles]. The folks on the beach here live comfortable, they go to sleep in a bed, but out there, you feel terror. Even in your chest you feel it. Your heart beats different.

Though Alvarenga arrived in Costa Azul by walking across sharp rocks and through thick coastal swamps, nearly everyone else reaches the town by way of a narrow paved road from Mexican coastal Highway 200. The seven-mile spur off the main highway ends at the Costa Azul waterfront and offers two options that cleave the town. Turn right and there are chic ecoresorts with flavorless Mexican food, twelve-dollar margaritas and private birding tours that capitalize on the fondness of English tourists of pecking incessantly at a personalized list of bird sightings. Palm-studded white sand beaches lure these tourists with the promise of privacy, virgin scenery, hummingbirds, rosy spoonbills, osprey and dozens more species that flitter and fly with abandon. The waiters may question the wisdom of allowing tourist children to frolic by the lagoons edge, where a crocodile the size of a station wagon visits frequently, but since they are never encouraged to express opinions to the guests or highlight local dangers, they keep their concerns to themselves. Most of the homes between the hotels have been purchased by local businessmen and politicians who envision a gold mine of tourism as soon as Mexico sheds its reputation as a bloodstained narco-state where bars occasionally get firebombed and waitresses decapitated. That is the nice side of the tracks.

On the left side of town sits a row of low-budget fishing shacks and an oceanfront dock packed with a dozen canoe-shaped boats twenty-five feet long and capable of hitting 50 mph, especially when powered by a pair of 75-horsepower Yamaha outboard motors. This is the part of town where Alvarenga arrived. He had a decades experience as a fisherman and hoped to find a boss or patrn willing to give him a shot at fulfilling his lifelong dream of being his own captain on a small fishing boat. But he needed to go slow. Visitors to this tough-guy neighborhood are immediately confronted with stares and a few basic questions. Who are you? What do you want? Like an IRA bar in Ireland or certain Italian restaurants in Bostons North End, Costa Azul maintains an insular tribal loyalty that binds the men together. There is no such thing as a casual visit to these quarters. A local fisherman suggests why the scene is so edgy: You want to see whats really going on in the Chiapas region? Go out to the island at two a.m. and watch all the narco-boats running north; they are moving two million dollars a night in cocaine up this coast. The entire police force for the state of Oaxaca [just north of Chiapas] has been paid off.

Alvarenga was not a narco or willing to run even the occasional cocaine bale up the coast, despite the promise of riches. At sea off the coast of Mexico, he had seen the savage fate of fishermen who gambled in the business of Los Kilos and run afoul of drug lords. Once he had motored up to a fishermans half-sunken boat and found the hull riddled with bullets. He tried to haul it home but it sank. There was no sign of the crew. Being eaten alive by sharks was probably the least violent way they could have died. At least sharks didnt torture.

Next page