Lost!

Thomas Thompson

IMAGE GALLERY

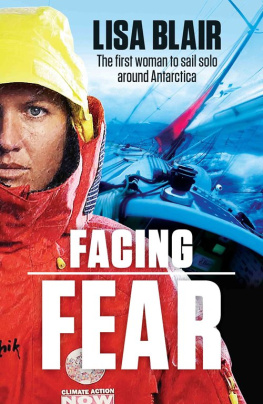

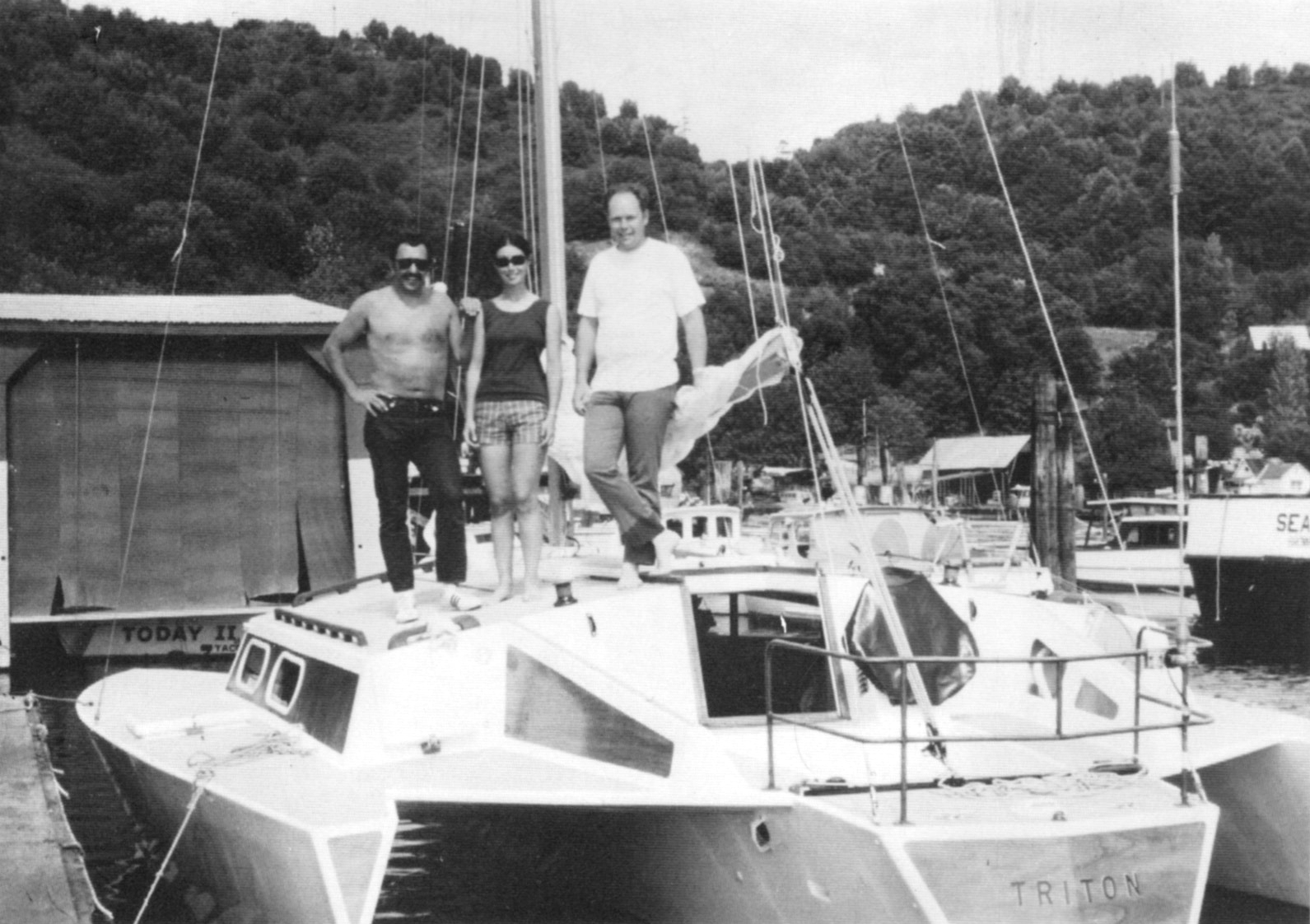

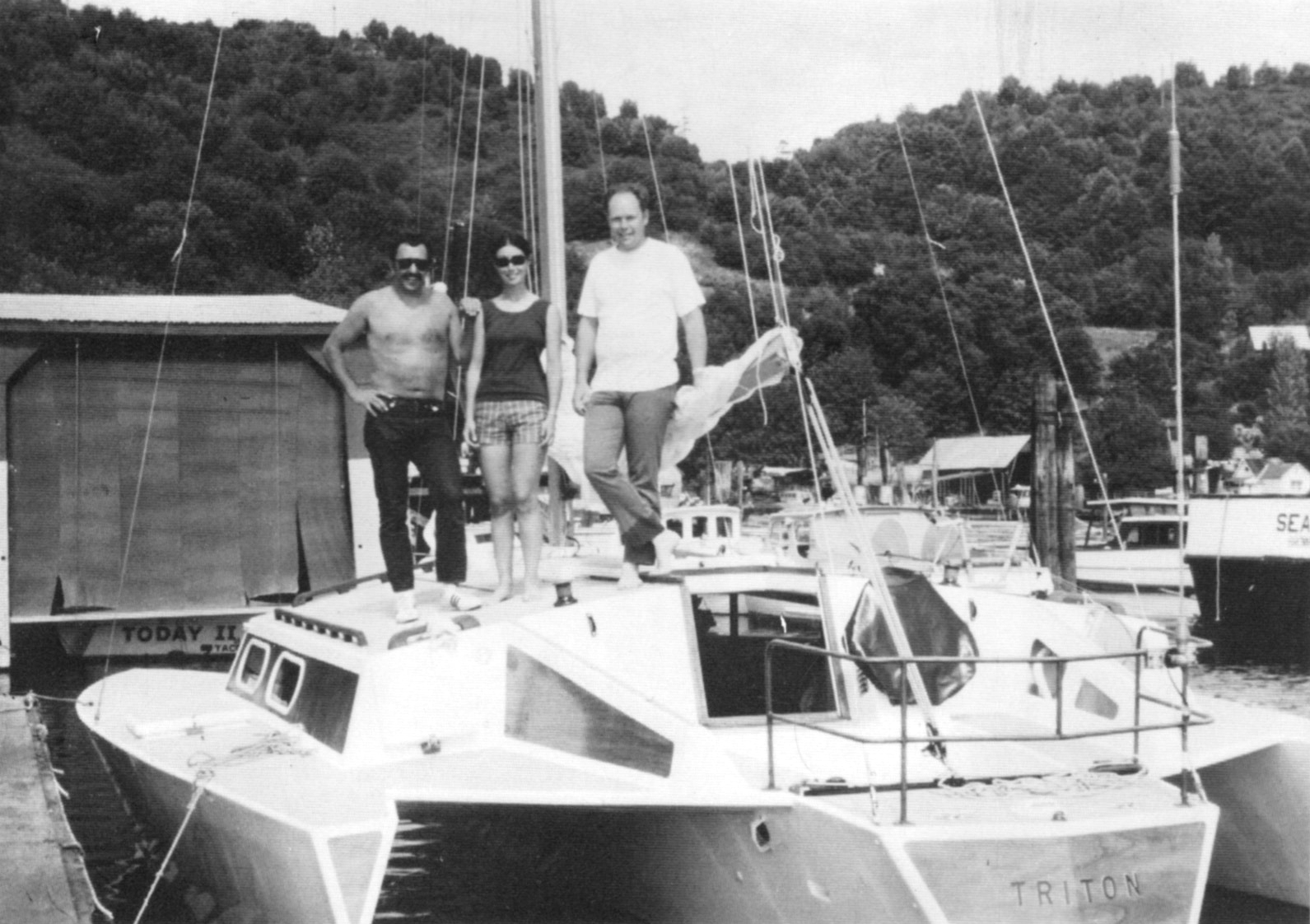

Bob Tininenko, his wife, Linda, and his brother-in-law, Jim Fisher, pose on the deck of Jims trimaran, the Triton, before their voyage.

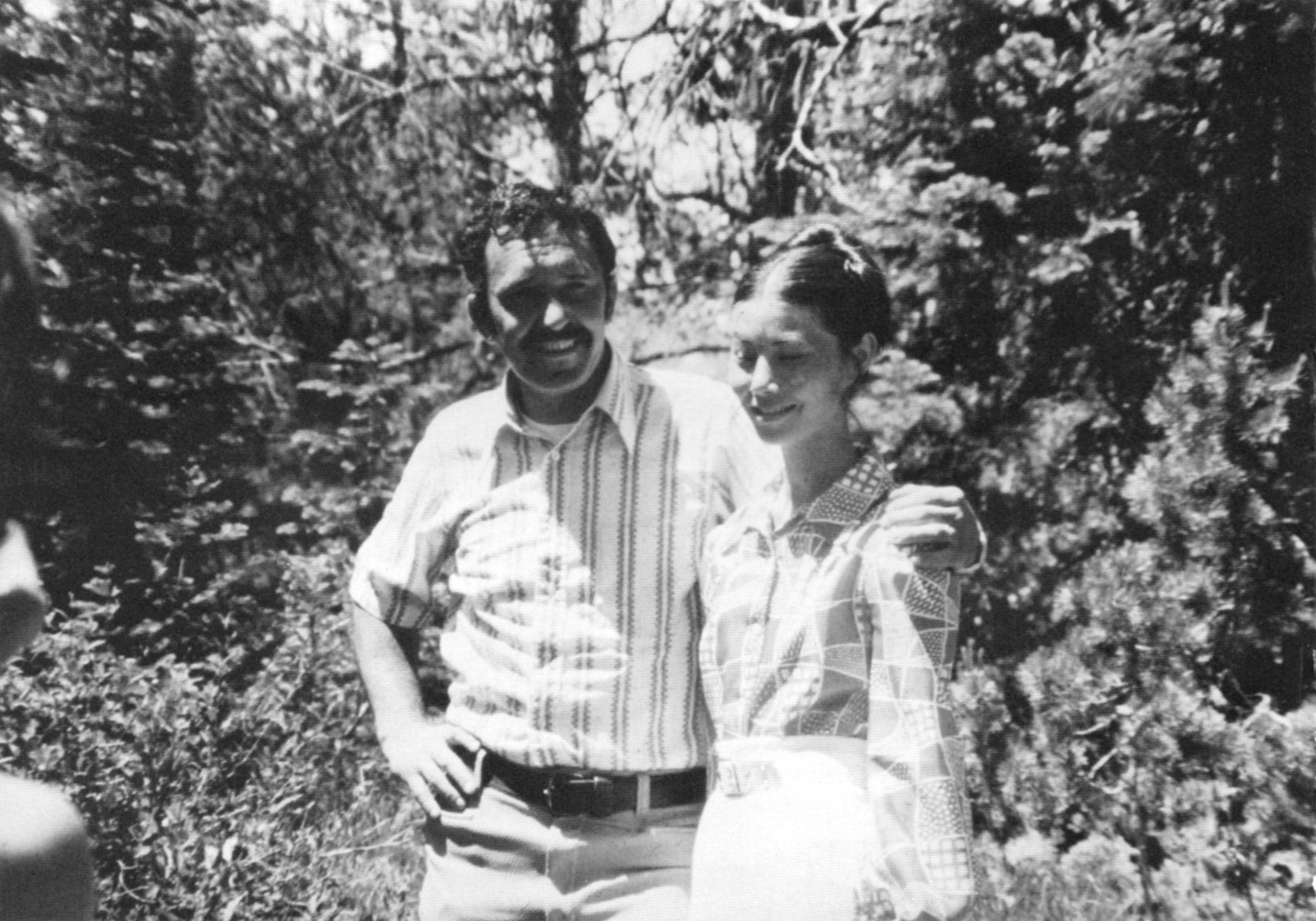

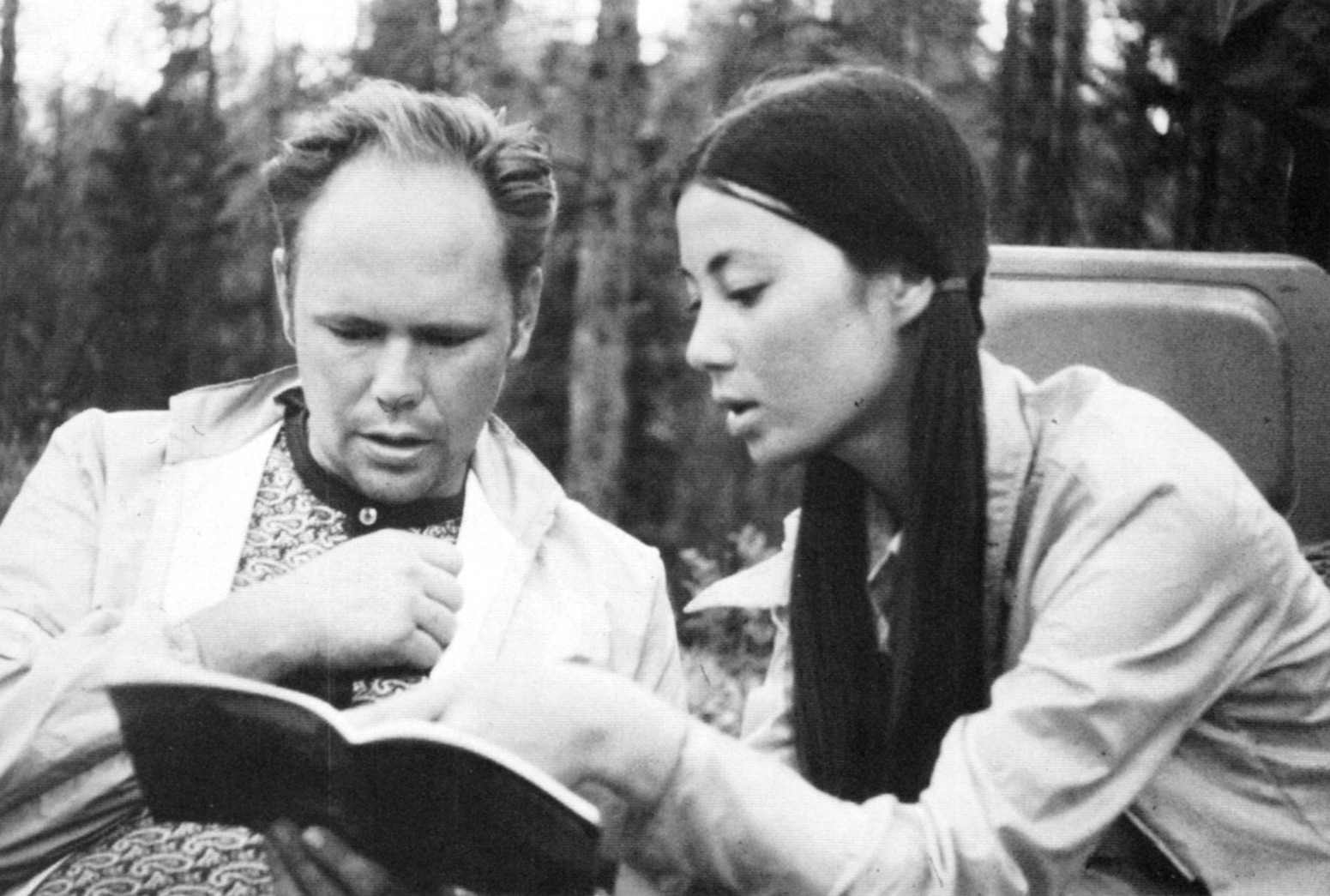

Bob and Linda.

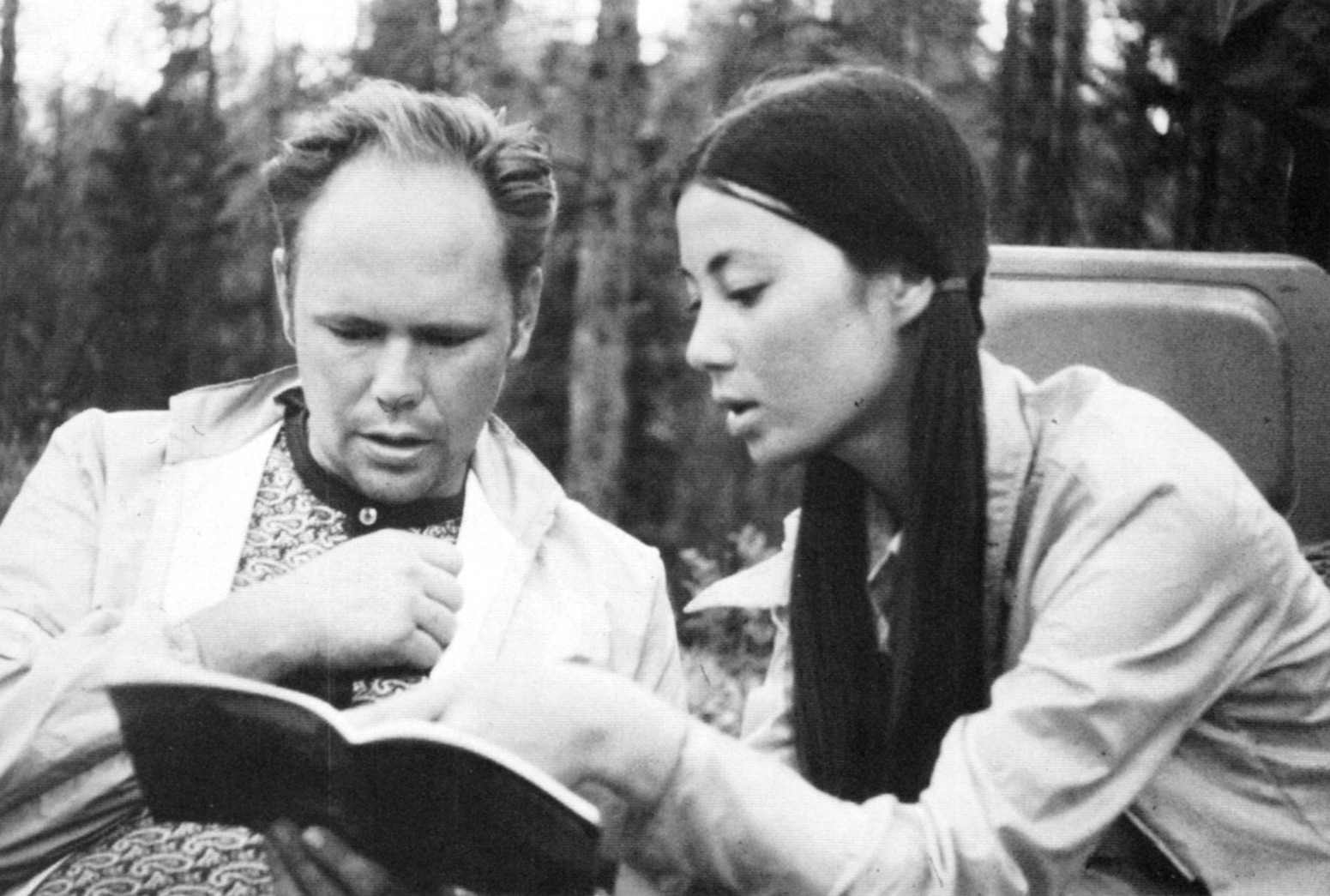

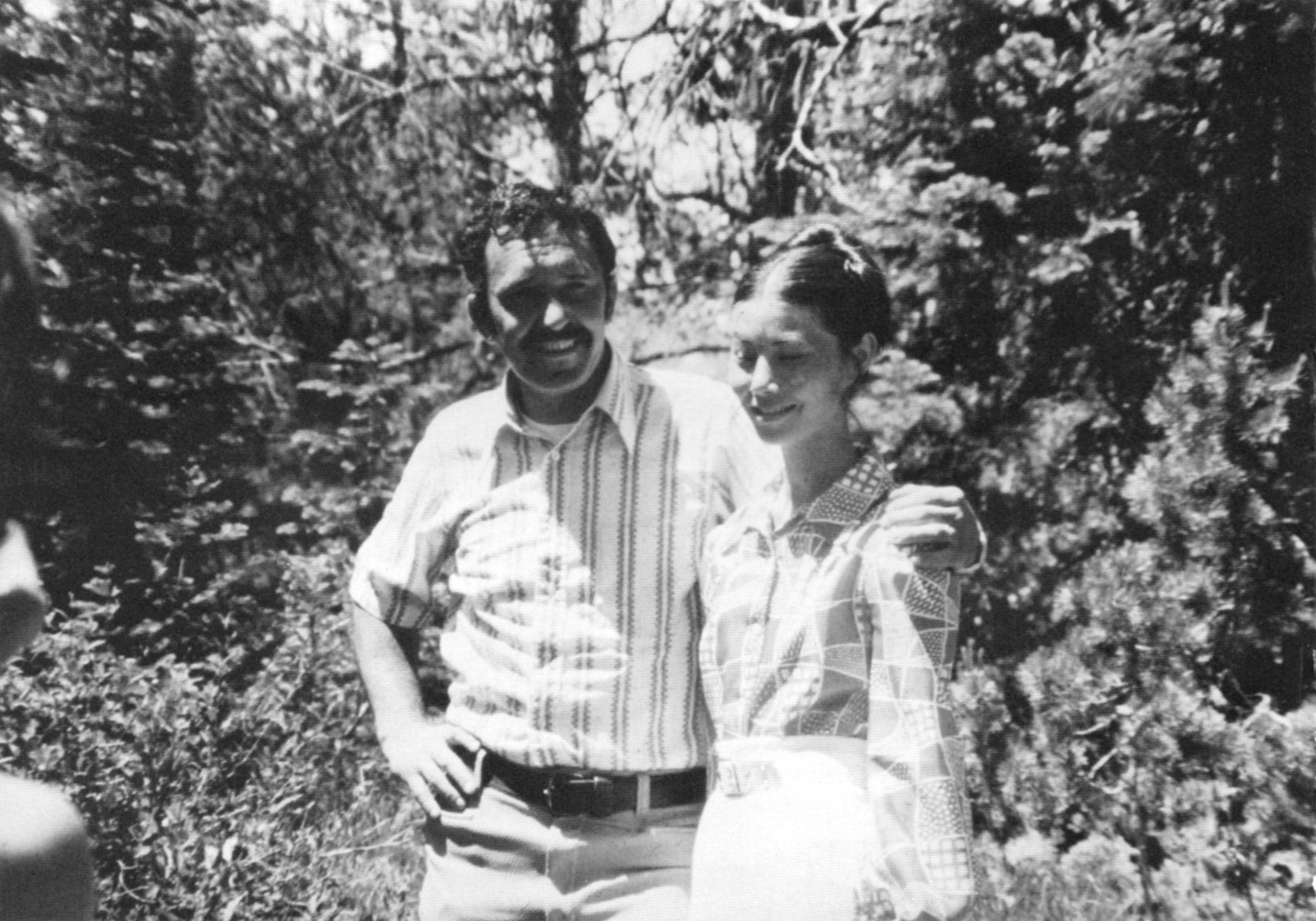

Jim and Linda.

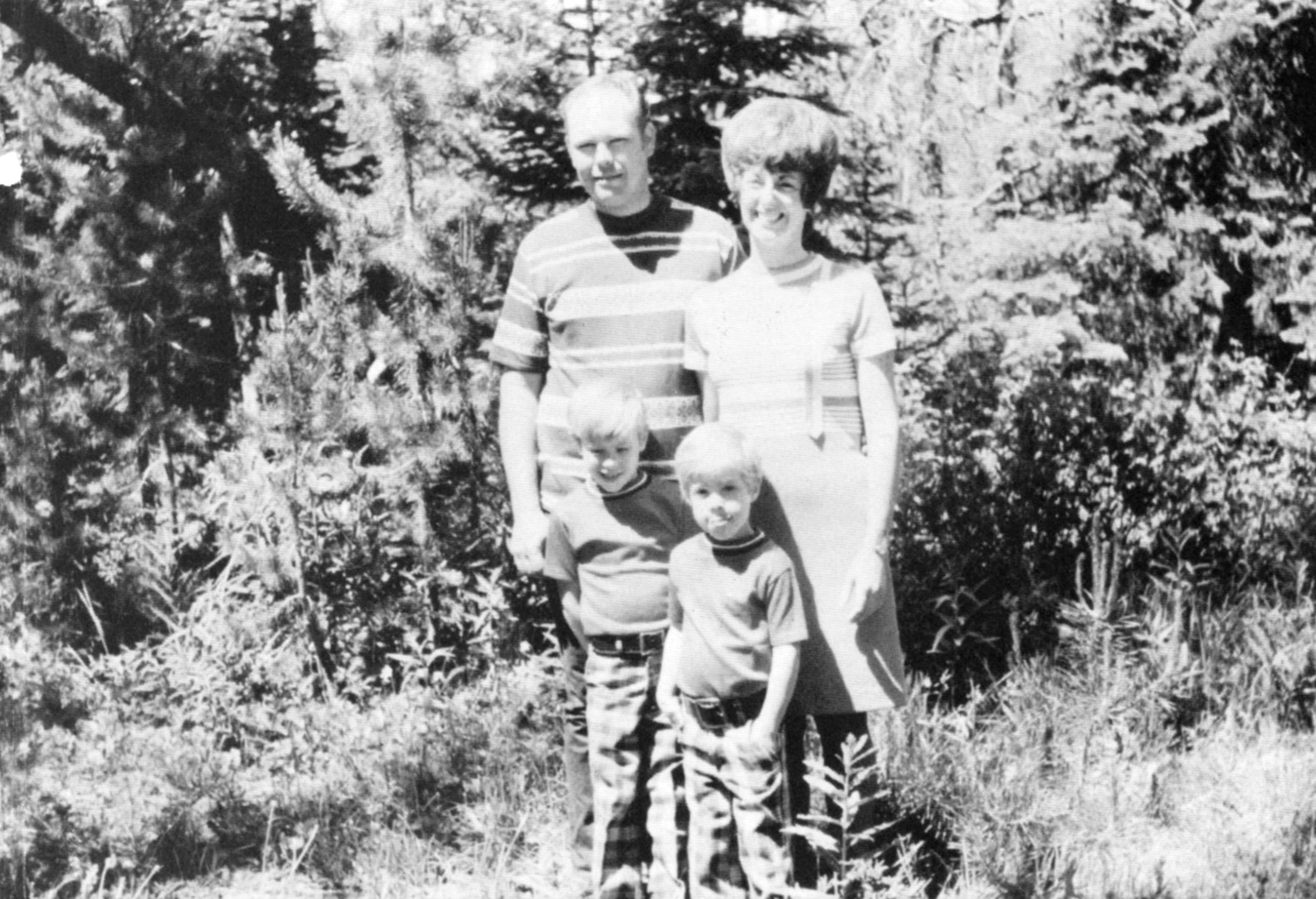

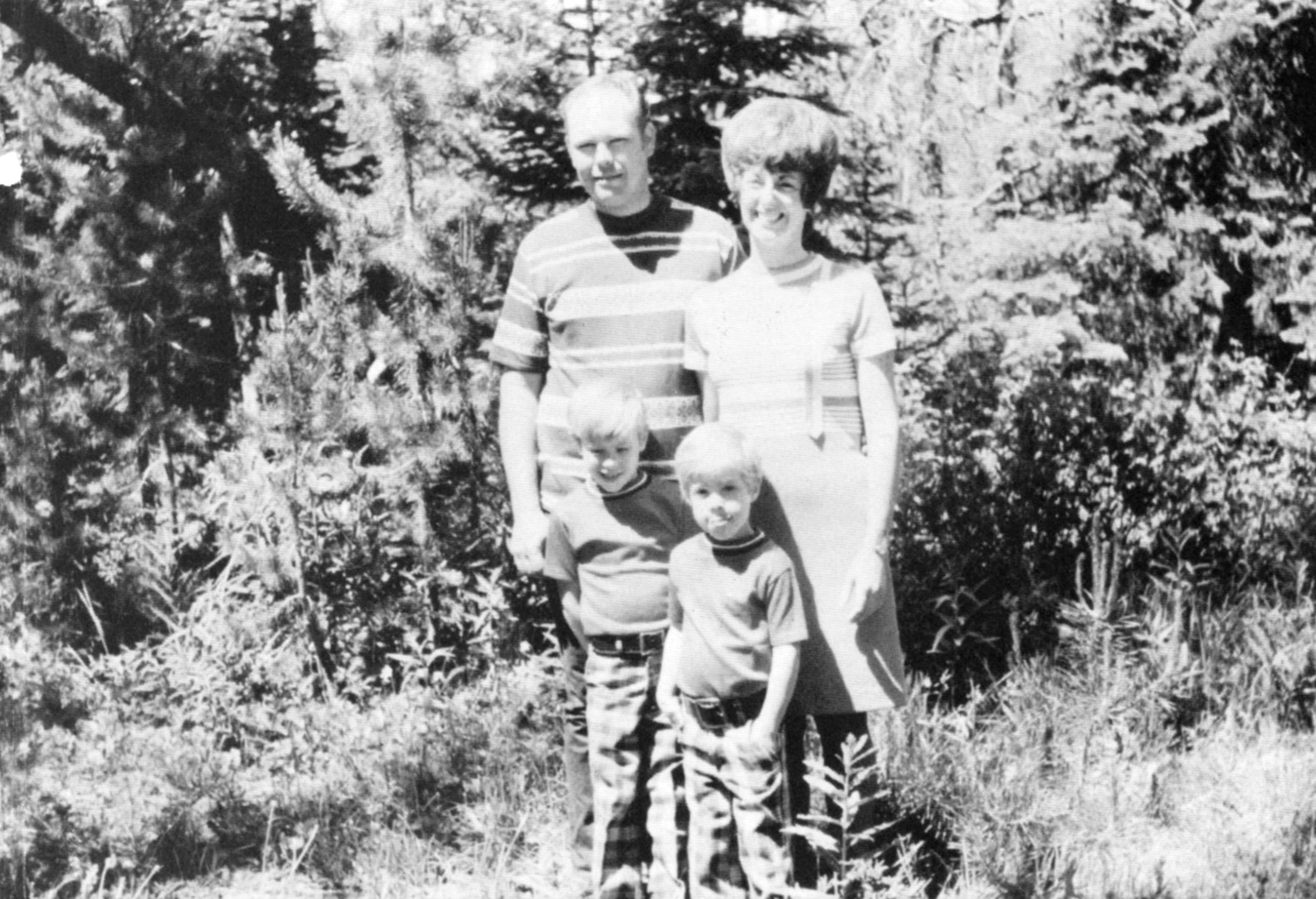

Jim, his wife, Wilma, and their two sons, Todd and Bradley.

The Triton under way.

There is, one knows not what sweet mystery about this sea, whose gently awful stirrings seem to speak of some hidden soul beneath the waves should rise and fall, and ebb and flow unceasingly; for here, millions of mixed shades and shadows, drowned dreams, somnambulisms, reveries; all that we call lives and souls, lie dreaming, dreaming, still; tossing like slumberers in their beds; the ever-rolling waves but made so by their restlessness.

But when a mans religion becomes really frantic; when it is a positive torment to him; and, in fine, makes this earth of ours an incomfortable inn to lodge in; then I think it high time to take that individual aside and argue the point with him.

Moby Dick

(1)

The soft summer wind abruptly died and it became eerily still, almost an omen. James Fisher stood in the bow pulpit of the thirty-one-foot trimaran he had built with his own hands, and he called out mightily to the God who dominated all of his days and nights. Dear Lord, he cried, his voice passionate in its summons, carrying across the windless hush of the Tacoma marina and causing the other yachtsmen at moor to look up, we ask for Your protection and guidance. We ask for Your hand upon the wheel. We ask for a safe journey, with a fair wind to fill our sails and hurry us to Your work. We ask that You watch over my brother-in-law, Bob, and his wife, Linda, and me, for we are Your children, going forth on a mission in Your blessed name.

The prayed-for brother-in-law, Robert Tininenko, glanced up. He would tolerate with courtesy any mans prayer, but he disliked being included when he no longer believed in that specific God. A decade before, Bob Tininenko had quit the church into which he had been born, the Seventh Day Adventists. His wife Linda, standing beside him, caught the tension and squeezed his elbow. If he had had any intention of interrupting the prayer to disclaim membership in the family of his brother-in-laws God, tactfully he did not.

As soon as the prayer was done, the Tininenkos were to leave on a sea journey of perhaps as long as fifty days with their brother-in-law, a man so devout, so unwavering in Adventist faith that he did not attend movies, watch television, drink coffee, utter curses, or even read the newspaper. Jim Fisher lived this life in preparation for a second and better one, in the arms of Christ, and he considered it his obligation to enlist others to do the same.

Get on with it, Jim, Bob muttered under his breath, looking at the fast-dwindling sun. Already they had been delayed most of the day while Jim and a friend tinkered with the radios, setting the antennae and tuning in the frequencies. If the religious exhortation stretched on much longer, darkness would cover their leave-taking. And Bob did not relish threading through a harbor and into Puget Sound at night.

Still, Jim prayed on. We further ask, dear Lord, that You look after my beloved wife, Wilma, and our two sons, and our unborn child. We pray that You will watch over all of our loved ones and family members. We, Thy servants, dedicate this boat, this voyage, and our lives to You. Thank You for hearing and answering our prayers, dear Jesus.

Bob squeezed Lindas hand and she could feel his impatience. But now the prayer was concluding.

Amen! For another moment, Jims body trembled, as if a force had passed from the unseen into his outstretched hand and down into the muscles and fibers of his husky body. Then he touched the steering wheel of his sailboat as if to transfer this divine power. He nodded.

Ready? asked Bob.

Lets go, said Jim. Only now it was his normal voice, reticent, soft, rather like the tone used by people who fear their remarks will be of little interest to anyone. Only in conversation with the Almighty did Jims voice fill and rise.

Thus at days end on July 2, 1973, with the one man moving surely to disengage the lines and the other firing up the small motor to replace the absent wind, did the Triton and its crew of three ease out of the marina and into Puget Sound. From there the graceful, gleaming white craft with blue hull and yellow trim would, on the third day, enter the Pacific Ocean, make a broad turn to the south, and follow a carefully prescribed course alongside and down the western coast of the United States, past Mexico, andif their calculations were accurate and the winds benevolenttie up finally in Costa Rica thirty to fifty days hence.

It had arisen suddenly, the idea for the adventurous summer voyage. In early May, as the academic year neared its end at the Adventist high school in Auburn, Washington where Jim served as registrar and occasional instructor of German, a letter arrived. Upon reading its contents, the stocky, blond young man bowed his head and prayed with sudden happiness. At long last, it had happened. God had answered his prayer. An invitation for missionary work!

That night Jim rushed home and thrust the letter upon his wife, Wilma. Reading it hurriedly, she shared her husbands excitement. Together they prayed their thanks.

Well, asked Jim quickly, when their prayer was done, what do you think?

Wilma scanned the letter again. I have never interfered in what you want to do, she said. You must do what you believe is the Lords will. You make the decision.

The letter was from Elder Fleck, a retired Adventist minister who was establishing a bakery in San Jos, Costa Rica. His intention was to employ Costa Rican youth to work in the bakery, to pay them good salaries, and to convert and proselytize for the church. If the bakery made profits, they would be used to establish other small industries and to further spread Adventist doctrine. It was a way of combining missionary and business activities, two objectives in which the Adventists are traditionally strong.

Elder Fleck wanted Jim Fisher to be his administrative aide at the bakery and to start up other light industry, such as broom and mattress factories. If Jim accepted, it would be a four-year commitment. But the pay would be meager and the living conditions hard.

Jim and Wilma Fisher had always lived frugally, both by religious intent and because he made only $400 a month in his job at the Adventist high school. Their home was rented from the church for $50 a month. Their clothes Wilma sewed or bought from Goodwill, their vegetables (they ate no meat) came from a home garden, their furniture was built by Jims hands. There was no television set, no newspaper subscription, no budget at all for entertainment other than family outings to collect Indian artifacts along the Columbia River or seashells near the Sound. But even with a strict ten per cent of their income going to the Adventist tithe, the Fishers were not in debt, nor did they consider their lives barren. Theirs was the good and hard life of an unfrilled America, an America where credit cards and installment buying did not exist, an America where family roles were sharply definedfather as wage earner and disciplinarian, mother as homemaker and teacher of the young, children as obedient and dutiful progeny. It was and always would be thus in the Fisher family.