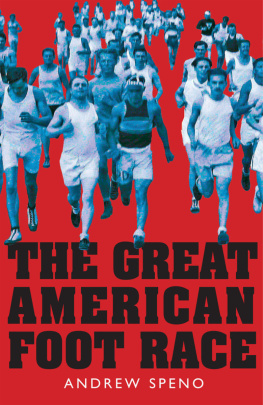

C. C. PYLES AMAZING FOOT RACE

THE TRUE STORY OF THE 1928 COAST-TO-COAST RUN ACROSS AMERICA

GEOFF WILLIAMS

Tantor Media, Inc.

2 Business Park Road

Old Saybrook, CT 06475

www.tantor.com

C.C. Pyles Amazing Foot Race:

The True Story of the 1928 Coast-to-Coast Run Across America

Copyright 2007, 2013 by Geoff Williams

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission except in the case of brief quotations for reviews or critical articles.

Printed in the United States of America.

ISBN: 9780988349469

Front cover photo courtesy of the UCLA Charles E. Young Library Department of Special Collections, Los Angeles Daily News Photographic Archives.

Jacket design by Mike Campbell.

For Susan, Isabelle, and Lorelei

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

T he following story is nonfiction. Every bit of it, as ridiculous as some of it may seem, is true to the best of my research. Some anecdotes came directly from the runners descendents, and some facts from books, court documents, and census records. But by far, most of the information in the following pages is compiled from the nuggets of news left by the reporters covering the story. The sportswriters of that era were known for their creative license, but if the occasional offbeat quote or anecdote came from a reliable source, such as the Associated Press, I chose to assume that the fantastic probably was accurate. After all, perhaps more than any other event, the Bunion Derby embodies the Roaring Twenties, a decade known for being over the top, comically surreal, and plain old fun. Besides, C. C. Pyle would have wanted it that way.

PROLOGUE: THE AGE OF ENDURANCE

On January 16, 1927, swimmers, some slathered in grease to keep warm, line up for a 22-mile race from Catalina Island to Los Angeles. The race likely influenced C. C. Pyles decision to hold a competition of his own on land. (Courtesy of the Catalina Island Museum Collection.)

E very decade has a cultural touchstone: The sixties gave us Woodstock; the seventies, Saturday Night Fever ; the eighties, larger-than-life iconslike Ronald Reagan, Princess Diana, and for a while, Michael Jackson; the nineties, the Internet; and the turn of the 21st century, the grim anniversary of September 11.

In the Roaring Twenties, endurance competitions ruled. History buffs know of flappers, bootleg gin and Prohibition, Chicago gangsters, Rudolph Valentino, and Harry Houdini, but above all, what separates that decade from all the rest is its endurance fads.

Anywhere in North America, if you had a passion or an interest, you could probably find a related endurance contest to enter. The dance marathons are the most remembered of the decade: Contestants jitterbugged or did the Charleston or some other step for days and even weeks at a time, taking a brief 5-minute break every hour to grab some food or go to the restroom. The couples even slept while dancing, alternating who would stay awake and keep their dozing partner propped up.

If dancing wasnt your thing, there were swimming endurance races. Or perhaps you would rather bowl? In June 1924, Hans Nelson became the world champion of endurance bowling, having won 50 games in a row against five veterans, in 7 hours. In August 1927, Owen Evans, 19, played golf for 17 hourswith no breaksand used a flashlight to see the ball in the dark.

But endurance competitions werent reserved only for sports. In the mid-1920s, endurance eating and drinking took the spotlight. At a New York hotel, Kathleen Hayden consumed 36 raw eggs in 85 minutes. Billie Pern, of New York City, drank 27 cups of coffee in a row. That was nothing compared to Gus Comstock, of Fergus Falls, Minnesota, who in 1926 consumed 62 cups of coffee in 10 hours but then was trounced by an Amarillo, Texas, man who drank 71 cups in less than 9 hours. In 1927, Comstock rallied by drinking 85 cups in 7 hours and 15 minutesonly to lose his title to Frank Truckimowicz, of Ray, North Dakota, who pretty much finished the conversation by consuming 90 cups of coffee in 3 hours and 28 minutes.

There were contests that involved devouring sandwiches, flapjacks, hot dogs, and spaghetti. Chicagos Cadarino Nezareno became pasta champion of the world after consuming 7 feet of spaghettiper minutefor 3 straight hours.

Adults broke records for staying awake the longest and for kissing the longest. Children were recorded flying kites for 2 days and nights and bouncing balls more than 2,000 times, all trying to achieve some legacy among world record holders. Almost as famous as the dance marathoners were the flagpole sitters. Shipwreck Kelly inspired numerous men and women to copy his successful sitting on flagpoles, for days and weeks at a time.

One of the most enduring images of the era is comedian Harold Lloyd, dangling from a clock on a high-rise building in Safety Last! , a film released April 1, 1923, that paid tribute to the endurance era. In the film, he climbed up a building to bring publicity to the store he worked for. In real life, a few weeks before Lloyds film premiered, Harry Young was scaling the side of the Hotel Martinique when on the 10th floor he lost his grip and plunged to his death in front of 20,000 people, including his horrified wife.

That was the fine print of the endurance era: The activities were risky.

No one drowned on January 15, 1927, during the 22-mile swimming race from Catalina Island to the California mainland, but it didnt go well for many participants. One man tied firewood to his back, thinking it would help him float (it didnt). Another man put on layers of clothing and covered himself in swimmers grease, all designed to keep him warm, but failed to consider how the soaked material would weigh him down. Making matters worse, he tied his shirt sleeves and pant legs securely around his wrists and ankles but forgot about his neck, and so the ocean swept into his clothes, filling him up like a water balloon. In the hours ahead, many swimmers were dragged into boats. As one syndicated newspaper account put it, they were delirious and raving. Their bodies were numb and marked with purple spots. Their teeth chattered, and they limped like wet rags.

The country loved it. The swimming race was all anyone talked about, especially after 17-year-old Canadian swimmer George Young reached the shoreline at 3:41 a.m., welcomed by a crowd of 5,000 spectators who wanted to get a good look at the young hero. And they got a very good look. A few seconds later, Young dashed back into the water, having just remembered that his swimming trunks had fallen off.

In the aftermath of Catalina Island, and in the midst of flagpole sitting, dance marathons, and rocking chair derbies (where people spent days trying to be the last person sitting and still rocking), one man watching from the sidelines finally decided to step forward. C. C. Pyle, who made his fortune as a sports agent, had an idea.

It would be the mother of all endurance contests. On April 26, 1927, at a Los Angeles press conference full of sportswriters, Pyle proposed a foot race across the United States.

The concept would evolve over a period of months, but his original vision remained more or less intact until March 4, 1928, when 199 men set off from Los Angeles in an attempt to race each other to New York City. Pyles notion was that any interested man could participateprovided he paid his $125 entry fee, $100 of which would be returned at the end of the participants involvement, to allow him to have money to return home. Whoever had the fewest collective hours after passing the finish line would win $25,000. It was prize money that matched what George Young received for Catalina, but Pyles endurance competition upped the ante. Second place would win $10,000. Third-place prize money was $5,000. Fourth, $2,500. And the fifth- through 10th-place winners would each get $1,000. All in all, Pyle promised to award $48,500 in cash, an astounding amount of money in 1928. Using the consumer price index, it would be like doling out almost one-third of a million dollars today.

Next page