Text copyright 2017 by Andrew Speno

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, please contact .

Calkins Creek

An Imprint of Highlights

815 Church Street

Honesdale, Pennsylvania 18431

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-62979-602-4 (hc)

ISBN: 978-1-62979-797-7 (e-book)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016951179

First e-book edition

H1.1

Designed by Barbara Grzeslo

Production by Sue Cole

Titles set in Aachen Std Bold

Text set in Frutiger LT Std 55

For Brian:

small steps,

even stumbles,

but relentless

forward progress

CONTENTS

FINISH

Index

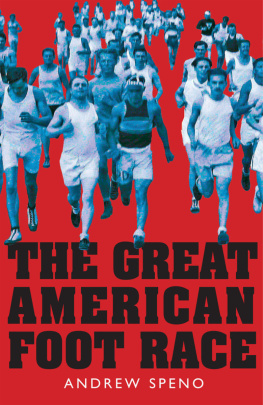

Director General C. C. Pyle gives commands from the sidelines.

START

Boom!

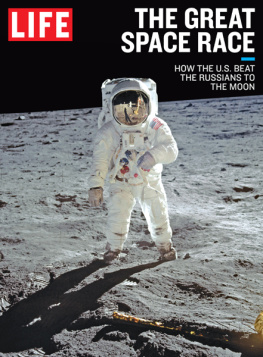

A buzz of excitement filled the air on the opening day of C. C. Pyles First Annual International Transcontinental Foot Race. Thousands of spectators surrounded the track at Ascot Motor Speedway outside Los Angeles. Tens of thousands more lined the road leading out of town. No matter where they stood, the crowds sensed that they were about to witness history.

Inside the Ascot oval, one man commanded the scene. Six-foot-two inches tall and broad-shouldered, Charles Cassius C. C. Pyle literally stood out above the rest. Normally stylish, he was dressed casually for the outdoor athletic event. He wore an ordinary tweed flat cap and a simple knit sweater, no bow tie to be seen. Yet Pyle couldnt resist at least one nod to fashion: he had laced up leather boots all the way to his knees. Lifting a megaphone, the Director General, as he called himself, barked instructions to the assembled athletes.

These were distance runners about to take part in the greatest, most stupendous athletic accomplishment in all history, as Pyle had put it. Not that they all looked the part. Their bodies came in many shapes and sizes: the tall and the small, the thick and the thin, the young and the old. (The youngest was just fifteen; the oldest all of sixty-three.) Their skin came in many shades of light and dark, though all would darken considerably in the coming weeks under the glare of the sun. They spoke more than a dozen languages. They hailed from twenty different countries and thirty different U.S. states.

Led by a small marching band, the transcontinental foot racers march onto Ascot Motor Speedway before a crowd of hat-wearing sports fans.

In the training days leading up to the start, one runner had been known to wear a business suit on the track, looking fit to run a bank, not a foot race. Another had dressed in flowing biblical robes, as if he had just walked off a movie set in nearby Hollywood. (He had.) A scruffy teenager with a ukulele strapped to his back and two mangy dogs in tow had wandered into the training grounds making noises about joining the race as an unofficial entrant. (He tried.)

But today, every runner was spiffed up in clean white athletic wear, including a racing singlet that read: C. C. Pyles L.A. to N.Y. race.

The 199 registered runners lined up on the track in ten rows, ready to begin a 3,400-mile race that would take them all the way from Los Angeles to New York City on the power of their own legs. They would run an average of forty miles a day, every day, for the next eighty-four days. Nothing like it had ever been tried in the history of the world. Would the athletes hold out? Could their bodies take the punishment? No one knew for sure, but they did know that Pyle had promised $25,000 to the runner who could get there first. This was a fortune in 1928, enough money to give a young man a good start in life: pay for college, a new automobile, and a modest-sized house. Enough for a working man to give his kids a decent education and a fresh start in life.

One hundred ninety-nine men. One goal.

Boom! The cherry bomb that signaled the start of the race exploded. C. C. Pyles First Annual International Transcontinental Foot Race had begun!

THE AGE OF BALLYHOO

We are living in a fast age,

and the professional athlete who is willing to sacrifice his bones and gore on the altar of a highly seasoned sport is the man of the hour in his line.

Bill Pickens, sports promoter

The year was 1928. The height of the Roaring Twenties. A time of optimism, when increasing numbers of Americans had money to spend and more leisure time in which to spend it. It was the Age of Ballyhoo. A time of excess, when publicity-seeking Americans tried to top each other with ever more outrageous stunts.

Dance marathoners gyrated on gymnasium floors for days on end. Alma Cummings started things off in the spring of 1923 when she danced twenty-four hours straight and three more for good measure. Over the next three manic weeks, endurance dancers extended the record nine times to ninety hoursalmost four full days. Most of the record-setters were young women who danced alone and with unscheduled pauses for bathroom breaks. But, as the decade progressed, partner dancing became the norm, and rest periods became standardized and more generous (fifteen minutes for each hour of dancing). Organizers began charging admission for spectators (the prices went up the longer the marathon continued) and awarding prizes to the winners (anywhere from $50 to $5,000). The turkey trot, foxtrot, and tango were the popular dances, but no special moves were required as long as the dancers kept swaying to the music. In the middle of the night, contestants took turns napping while their partners propped them up. But they would be eliminated if they let a knee or hand touch the ground.

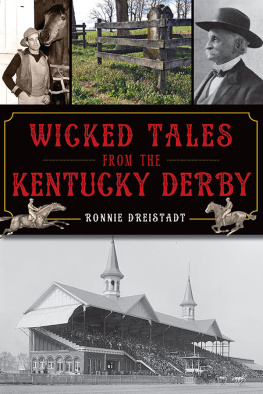

The marathon dance is almost over for this pair. The man has succumbed to the sweet temptation of sleep, while the woman struggles just to keep him off the floor.

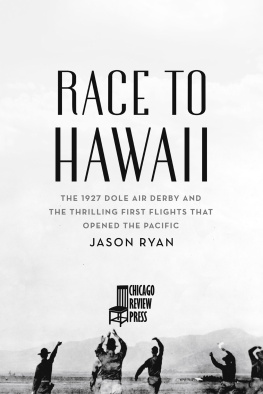

In another fad, pole sitters sat atop flagpoles for weeks at a time. Alvin Shipwreck Kelly was the first to mount a pole in 1924 and, by the end of the decade, had extended his record from thirteen hours to a mind-boggling forty-nine days! When he needed food or a toothbrush or razor, assistants sent it up by pulley. Most important, Shipwreck taught himself to sleep sitting upright with his thumbs in a pair of holes in the pole. If he leaned over while dozing, a tweak of his thumbs would wake him up.

Alvin Shipwreck Kelly sits atop a pole over the B. F. Keith Theater in Union City, New Jersey, 1929. During the course of his pole-sitting career, Shipwreck estimated he spent more than 20,000 hours aloft1,400 of them in rain, sleet, or snow!

Trained athletes also aimed to go farther and longer. In 1926, twenty-year-old American Gertrude Ederle became the first woman to swim the hard-cutting currents of the English Channel. Trudy, as she was called, covered her body in a thick coating of grease to insulate herself from the 60-degree water as she crossed from France to England. When a storm whipped up and churned the channel into twenty-foot waves, Trudys coach shouted over the roar for her to come out of the water. Trudy, who was going deaf because of complications from childhood measles, heard well enough to call back, What for? and kept on stroking. As evening fell, Trudy followed the light of bonfires and the sounds of noisy revelers on the southern England beach. She had swum thirty-five zigzaggy miles in 14 hours and 31 minutes, two and a half hours faster than the existing mens record. When she returned to the United States, two million New Yorkers cheered her in a ticker-tape parade.

Next page