Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the Print Version

JOHN LANCASTER

THE GREAT AIR RACE

Glory, Tragedy, and the Dawn of American Aviation

Liveright Publishing Corporation

A Division of W. W. Norton & Company Celebrating a Century of Independent Publishing

frontispiece: Library of Congress

Copyright 2023 by John Lancaster

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Jacket design: Jarrod Taylor

Jacket photograph: San Diego History Center

Book design by Patrice Sheridan

Production manager: Julia Druskin

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN 978-1-63149-637-0

ISBN 978-1-63149-638-7 (ebk.)

Liveright Publishing Corporation 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd. 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

In memory of my parents,Paul and Susan Lancaster

CONTENTS

, as it often does in the Wyoming high country, all but blinding the two aviators in their wood-and-fabric biplane. Hunched in the open front cockpit, Lt. Edward V. Wales reduced power and descended to within a few hundred feet of the ground, where the visibility was slightly better. But there was little room to spare beneath the clouds. Soon after the aircraft leveled off, the terrain started to rise. Wales advanced the throttle and began a slow climb.

some twenty minutes earlier, Wales and the man who rode in the cockpit behind him, Lt. William Goldsborough, had decided to fly the direct compass line to the temporary airfield at Fort D. A. Russell in Cheyenne, on the far side of the Medicine Bow Mountains. They briefly had considered a safer route along the Union Pacific Railroad tracks, which ran north of the highest peaks before veering south toward Laramie and Cheyenne. But the detour would have cost them valuable timeanother forty minutes or so at leastand the two were in a hurry.

Now Wales was having . The blizzard showed no sign of abating, and he knew that the tallest mountains were still ahead. Better to follow the railroad after all. He banked the DH-4 into a left turn, then flattened the wings on a new compass heading to the north.

Neither man was particularly worried. They could still see the ground and were . It wouldnt be long before they picked up the railroad and with it an unobstructed path across the prairie to Cheyenne, where fuel and food awaited. They could make up the lost time on the next couple of legs. With a tailwind and a bit of luck they might even reach Omaha by sunset. In the meantime, Wales was careful to maintain an even distance between the biplane and the moderate uphill slope. At more than 8,000 feet above sea level, the air was bitingly cold, but the aviators were used to it by now.

An . The cowboys would have heard the thunder of the big V-12 and if they were close enough would have recognized the tricolor roundels of the U.S. Army Air Service.

It was early in the afternoon of October 9, 1919.

__________

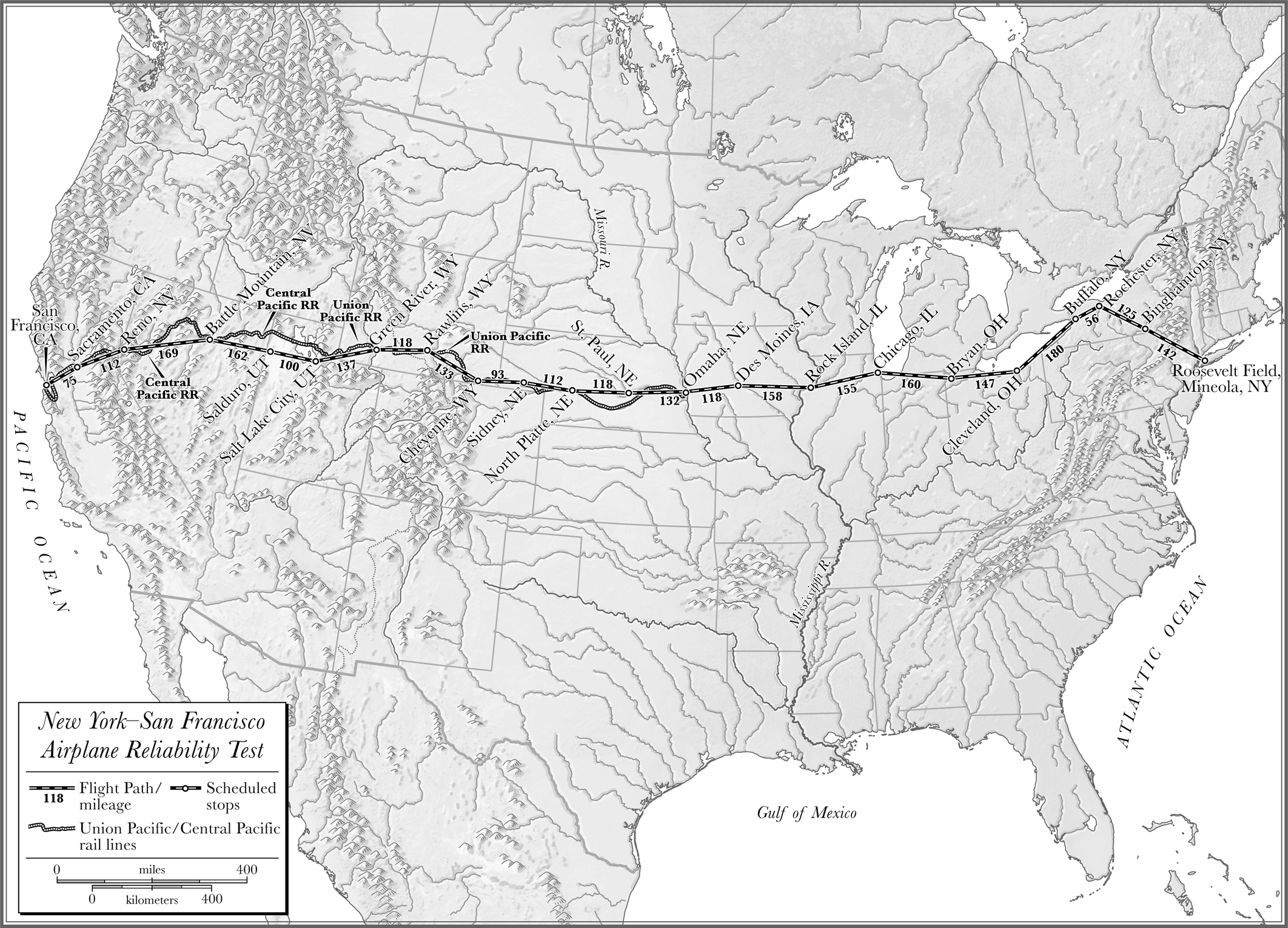

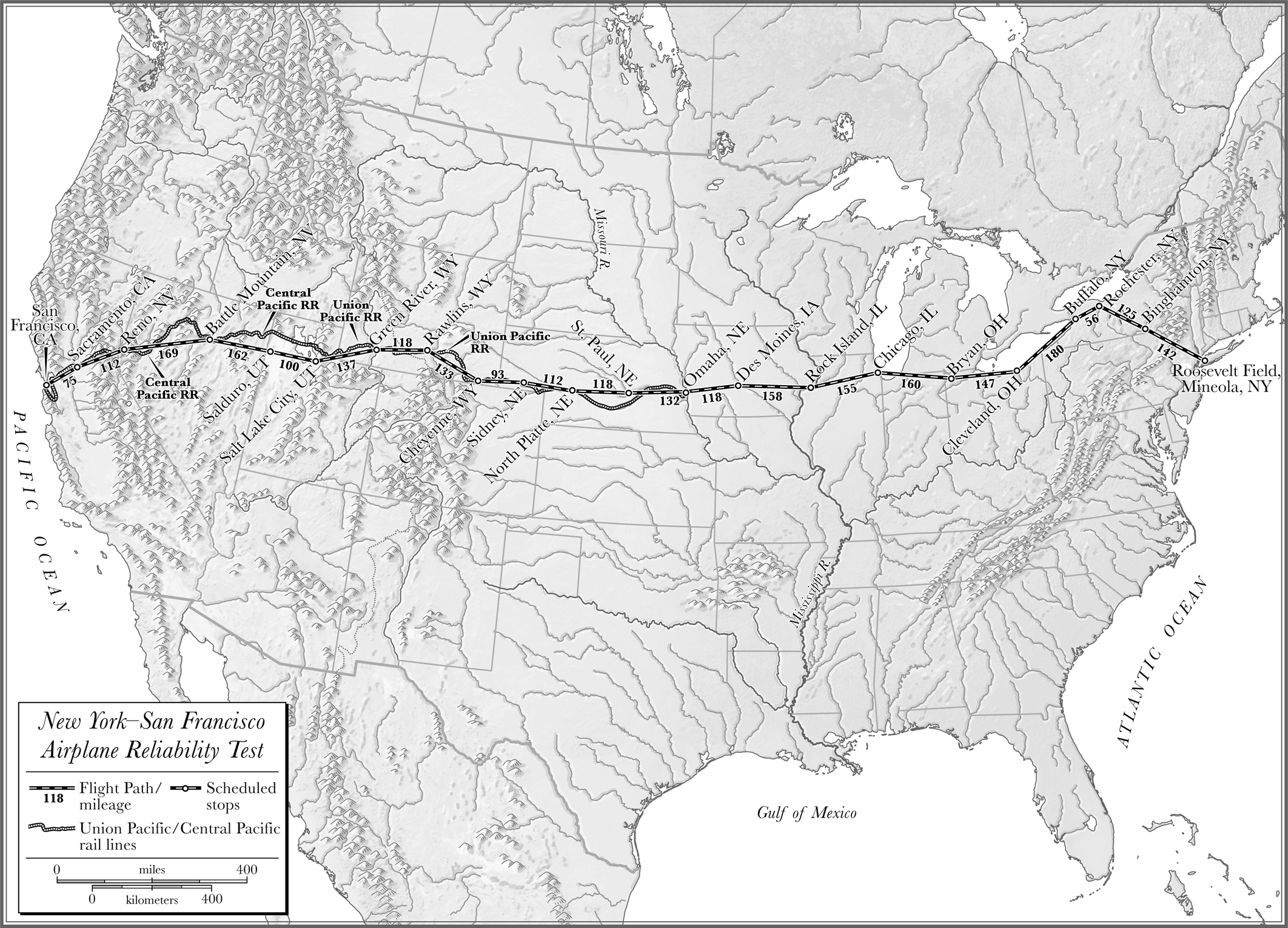

A little more than twenty-four hours earlier, the two flyers had departed San Francisco on the first leg of a grand adventurea coast-to-coast airplane race, the likes of which the world had never seen. As conceived by William Billy Mitchell, the brash, sharp-elbowed brigadier general and war hero who would one day be celebrated as the father of the U.S. Air Force, the Reliability and Endurance Test, as the race was officially known, would be unprecedented not only in length and duration but also in number of participants. More than sixty airplanes divided into two groupsone on Long Island, the other in San Franciscowould take off for the opposite coast some 2,700 miles distant, crossing in the middle and competing for the fastest flying and elapsed times.

It was a bold and risky undertaking. Though the race was open only to qualified military aviators, none of the men who signed up had attempted a journey of such improbable lengthand for good reason. Like all aircraft of the day, the surplus warplanes they would fly were almost comically ill-suited for long-distance travel or arguably for any travel at all. Open cockpits offered scant protection against wind and cold. Engine noise was, quite literally, deafening. Engines were unreliable and sometimes caught fire in flight. Crude flight instruments were of marginal value to pilots trying to keep their bearings in clouds and fog.

But that was only part of the challenge. The route across the country was almost entirely lacking in permanent airfieldsor any form of aviation infrastructure. There was no radar, air traffic control system, or radio network. Weather forecasts were rudimentary and often wrong. In the absence of electronic beacons or formal aviation charts, pilots followed railroad tracks or compass headings that wandered drunkenly with every turn. Every hour or twothey hopedthey would land at one of twenty control stops between the coasts. Most were makeshift grass or dirt airfields that had been hastily demarcated and stocked with fuel, spare parts, and other supplies, sometimes just hours before the start of the race. Despite these slapdash preparations, Mitchell and his colleagues in the Air Service decided at the last minute to double the length of the raceinstead of a one-way flight between the coasts, it would be a round-trip journey of 5,400 miles. It was as if, in the absence of anything resembling a national air transportation system, Mitchell had decided simply to will one into being.

__________

His motives were nakedly political. Though it had given birth to the airplane, the United States had been a latecomer to World War I and had fallen behind Europe in aviation, as clashing armies competed for dominance of the air over the Western Front. Now, as the United States rushed to demobilize, Mitchell feared that its long-term security was at risk. The country needed a robust aviation industry to fulfill both military and commercial needs. Part of the solution, he believed, was a cabinet-level department of aeronautics to include an independent air force, as called for by several bills pending in Congress. He also sought to protect the Air Service from the worst of postwar budget cuts. A gifted showman, Mitchell conceived the race as a stunt to demonstrate the transformative potential of aviation and rally the public behind his goals in Washington. To that end, he had a powerful ally in Otto Praeger, the driven, sometimes-ruthless Texan who ran the fledgling U.S. Air Mail Service and embraced the contest as a prelude to a transcontinental airmail route.

In one sense, at least, Mitchells timing was good. Despite the victory in Europe eleven months earlier, the country was fearful, anxious, and in need of a little distraction. The influenza pandemic, which ultimately would kill about 675,000 Americans, only recently had begun to recede. Many cities were in turmoil, as nativist mobs fueled by racism and anti-communist paranoia visited their fury on immigrants, unions, and especially African Americans, several hundred of whom were lynched during the so-called Red Summer of 1919. And Washington was rife with rumor and speculation over the health of President Woodrow B. Wilson, who recently had suffered a stroke. Against that backdrop, the contest came as a welcome respitean irresistible pageant of grit, daring, and skill that would play out over many days and thousands of miles.