Contents

Guide

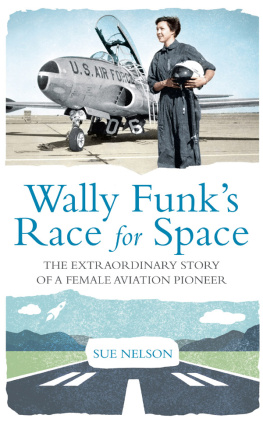

Wally Funks

Race for Space

THE WESTBOURNE PRESS

an imprint of Saqi Books

26 Westbourne Grove, London W2 5RH

www.saqibooks.com

First published 2018 by The Westbourne Press

Copyright Sue Nelson 2018

Sue Nelson has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All rights reserved.

ISBN 978 1 908906 34 2

eISBN 978 1 908906 35 9

Printed and bound by CPI Mackays, Chatham, ME5 8TD

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

For Wally

and all women who aim high

Contents

Preface

Preparing for Launch

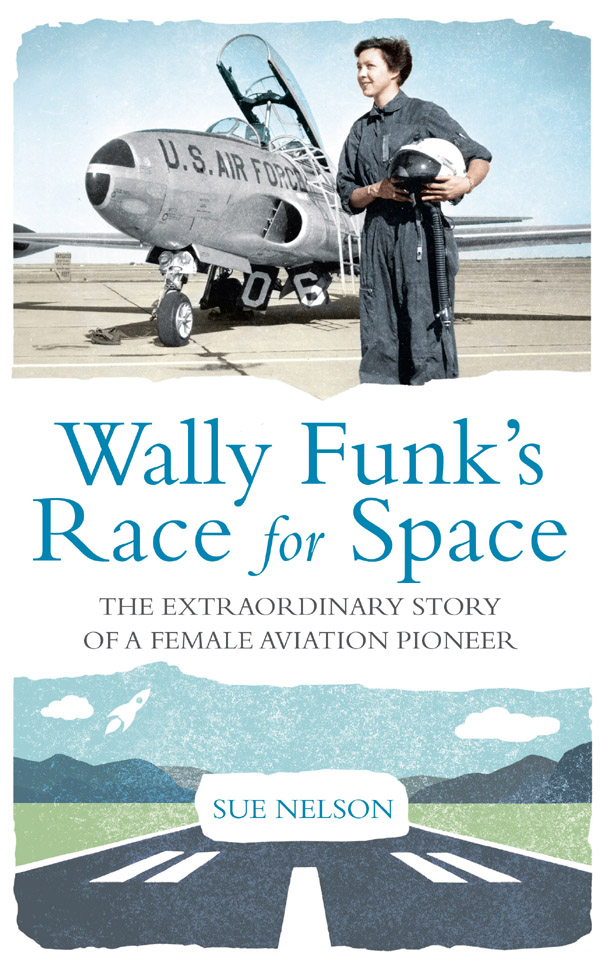

A Ford minivan rattled down a Dallas freeway at a chassis-shaking sixty miles an hour, no doubt loosening some of the ageing space stickers attached to the windows. As my fingers clutched the sides of the passenger seat, I prepared to die. It occurred to me that, after the inevitable crash, at least a personalised license plate would make us easier to identify. It read WF A womans place is in the cockpit.

WF stood for the drivers initials: a seventy-eight-year-old pilot called Wally Funk. Mary Wallace Funk, to be precise, but she refused to answer to Mary. Or Wallace. It didnt matter either way because it was obvious that she was better suited to flying a plane than driving a car as neither of her hands were on the steering wheel.

Her right hand groped around the back seat, searching for something. The van meandered worryingly into another lane. A piece of paper, wedged behind a visor, caught my eye. It appeared to be a medical form. The only discernible words were: Do not resuscitate. When my voice emerged it was part shout, part squeak.

Put your hands on the wheel!

Wally turned towards me with a mischievous smile and, all faked innocence, replied: What? Have you never driven with your knee before?

Meet Wally Funk. A woman born for descriptions such as force of nature, unstoppable and, at times, woman with a death wish. Over the last few years she has tried (unwittingly) to kill me several times and, though Wally might be surprised to hear this, I have also felt like killing her. Somehow we became friends.

We first met in 1997 when I was making a BBC radio documentary called Right Stuff Wrong Sex. The year before, I had read a couple of sentences in a US newspaper making a passing reference to the Mercury 13. At the time, like so many people today, I had never heard of them. The Mercury 13 were thirteen exceptional female pilots who, between 1960 and 1961, passed the same physical and psychological tests as the Mercury 7 Americas first astronauts as part of a privately funded programme led by Dr William Randolph Randy Lovelace II.

Wally Funk was one of those thirteen women with the right stuff. The funding, for reasons discussed later in the book, was cut with just a few days notice and none of these women ever made it to space.

As a feminist and space fan, I couldnt believe this incredible piece of hidden history had passed me by. I was determined to bring this story to a UK audience. The programmes title was a direct reference to Tom Wolfes The Right Stuff, a book about the selection and heroic achievements of Americas first (male) astronauts. It was broadcast in the UK on BBC Radio 4 in April 1997. A shorter version later aired in the United States on National Public Radio.

The Mercury 13s efforts made it into numerous newspapers during the 1960s, but over time the knowledge of these women has ebbed and flowed. Every so often their presence, like ripples on sand, disappears from public view as if all memory of their achievements has been erased. I often give talks about women in space, and whenever Ive thought, Everyone must know about the Mercury 13 by now, a room full of people has gazed at me collectively blank. Its a stark reminder that the recognition of these trailblazing women has a long way to go.

The aim of the radio programme in 1997 was to shine a renewed light on their story. I wrote a piece for the Guardian on the Mercury 13 and, within the following few months, Marie Claire and other publications followed up the story. Years later, I met someone who had helped set up an exhibition paying tribute to the Mercury 13 at the UKs National Space Centre in Leicester. Praising the exhibition, I enquired where theyd got the idea. I heard a programme on Radio 4, she said.

Wally and I kept in contact after our interview, then lost touch, were reacquainted over the phone, and then hooked up in person almost twenty years after our first meeting. Thats when she started becoming more than a work contact and became a friend. This book includes our meeting in 1997 but mainly focuses on several road trips weve made together by plane, train and automobile in the United States and Europe in 2016 and 2017.

Most of the Mercury 13 are no longer with us, but Wally is not only alive, her energy levels are the very definition of life itself. Life doesnt just happen to Wally. She makes it happen. Her past reveals an insight into her determination, but it is also the bare bones of this particular history. Because Wally is living history. Defining her by the five days when she took Lovelaces tests in 1961, or even by the phrase Mercury 13, misses out the extraordinary achievements she has accomplished within aviation. It also fails to recognise her lifetimes pursuit of the ultimate adventure. Wally never gave up on her dream of becoming an astronaut and remains determined to make it into space.

As you can tell, she is a formidable woman. Wally is the sort of character who could shoot, hunt and fish from an early age. The sort of woman more comfortable in trousers and boots than a skirt and heels. The sort of woman who can control a Ford minivan with her left knee. Wally is also the sort of woman who, if history had been kinder, might have been the first woman on the Moon. She has spent over fifty years trying to become an astronaut and get into space and is now, with the birth of commercial spaceflight, the closest she has ever been. It is a desire I can understand.

In 1974, I wrote to NASA as a British schoolgirl enquiring about how to become an astronaut. In a haze of youthful ignorance, I hadnt realised that, in order to be eligible as a NASA astronaut, you also had to be American. It wouldnt have made a difference even if I had known. Although Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space in 1963, NASA didnt admit women onto their astronaut programme until 1978. In my own small way, like Wally, I was ahead of my time.

As a journalist, I have enjoyed a life in space by proxy ever since. I reported on space missions for television and radio during my time as a BBC science correspondent. I make space-related documentaries for BBC radio, produce short films on space missions for the European Space Agency, and interview astronauts and space scientists for the Space Boffins podcast.