Text 2014 by Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

This book may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please write: Special Markets Department, Smithsonian Books, P. O. Box 37012, MRC 513, Washington, DC 20013

Air & Space / Smithsonian Magazine

Magazine Editor: Linda Musser Shiner

Senior Editor: Tony Reichhardt

Art Director: Ted Lopez

Published by Smithsonian Books

Director: Carolyn Gleason

Production Editor: Christina Wiginton

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as seen in the endnotes. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these images individually, or maintain a file of addresses for sources.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-58834-486-1

v3.1

Table of Contents

Preface

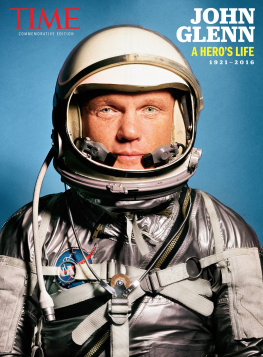

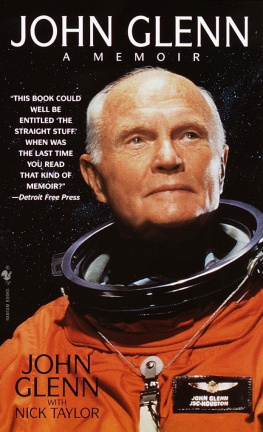

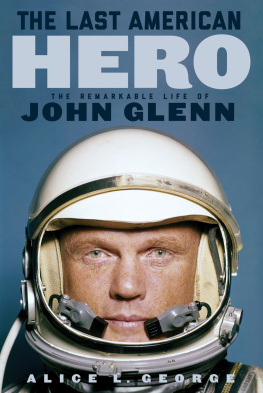

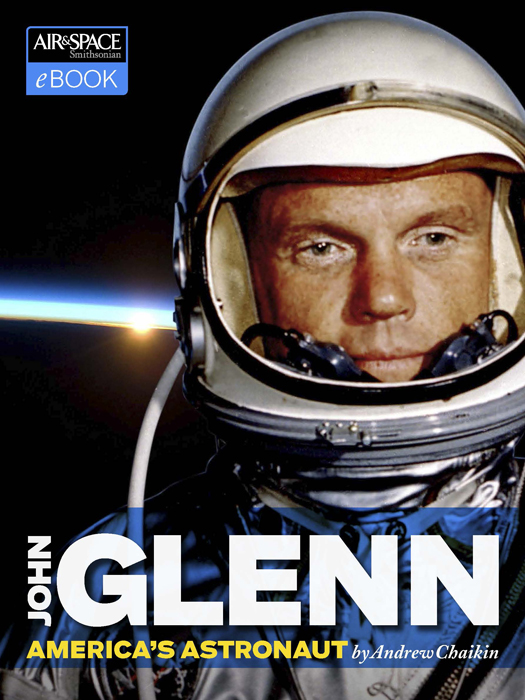

A few steps from the National Mall in Washington D.C., just inside the National Air and Space Museum, you can peer into the tiny cockpit of Friendship 7, the Mercury spacecraft in which John Herschel Glenn, Jr. became the first American to orbit the Earth on February 20, 1962. Today, with so many astronauts and cosmonauts making trips to the International Space Station that the public barely knows their names, its difficult for us to imagine the impact of Glenns five-hour, three-orbit flight. Still stinging from Soviet space firsts, including Yuri Gagarins single-orbit flight a year earlier, Americans were hungry to see their own man in orbit as proof of Americas Cold War superiority.

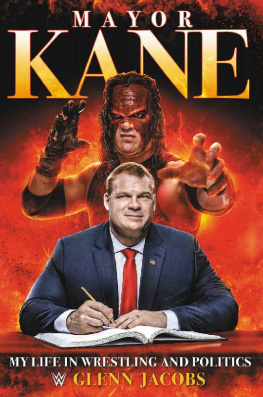

But the publics reaction to the three orbits of Friendship 7 was about more than the flight itself; it was also very much about John Glenn. This sunny, freckle-faced, all-American-boy from the heartland captured the national imagination. Outgoing and engaging, with a blend of determination, earnestness, and self-effacing modesty, he spoke unabashedly of his dedication to family and country. He seemed almost too good to be true. The original seven Mercury astronauts were household names even before they went into space. But after Glenn flew, he became nothing less than an icon.

Nearly 37 years later, the 77-year-old John Glenn, now a U.S. senator from Ohio, returned to orbit aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery as the oldest person ever to fly in space. Americas vintage space hero still resonated with the public: Unlike most of the dozens of previous shuttle flights, Glenns launch drew huge crowds to Cape Canaveral and massive media coverage of the nine-day mission.

Even today, in our celebrity-soaked popular culture, what is it about Glenn that has won him an enduring place of honor in the life of a nation? The answer emerges in his life story, from a rural, Depression-era Ohio boyhood through his careers as wartime aviator, test pilot, astronaut, Senator, and finally, elder statesman. Not only does John Glenn embody the story of 20th-century aviation and space exploration, he stands as a living emblem of the American Century. And his story, it turns out, isnt too good to be true.

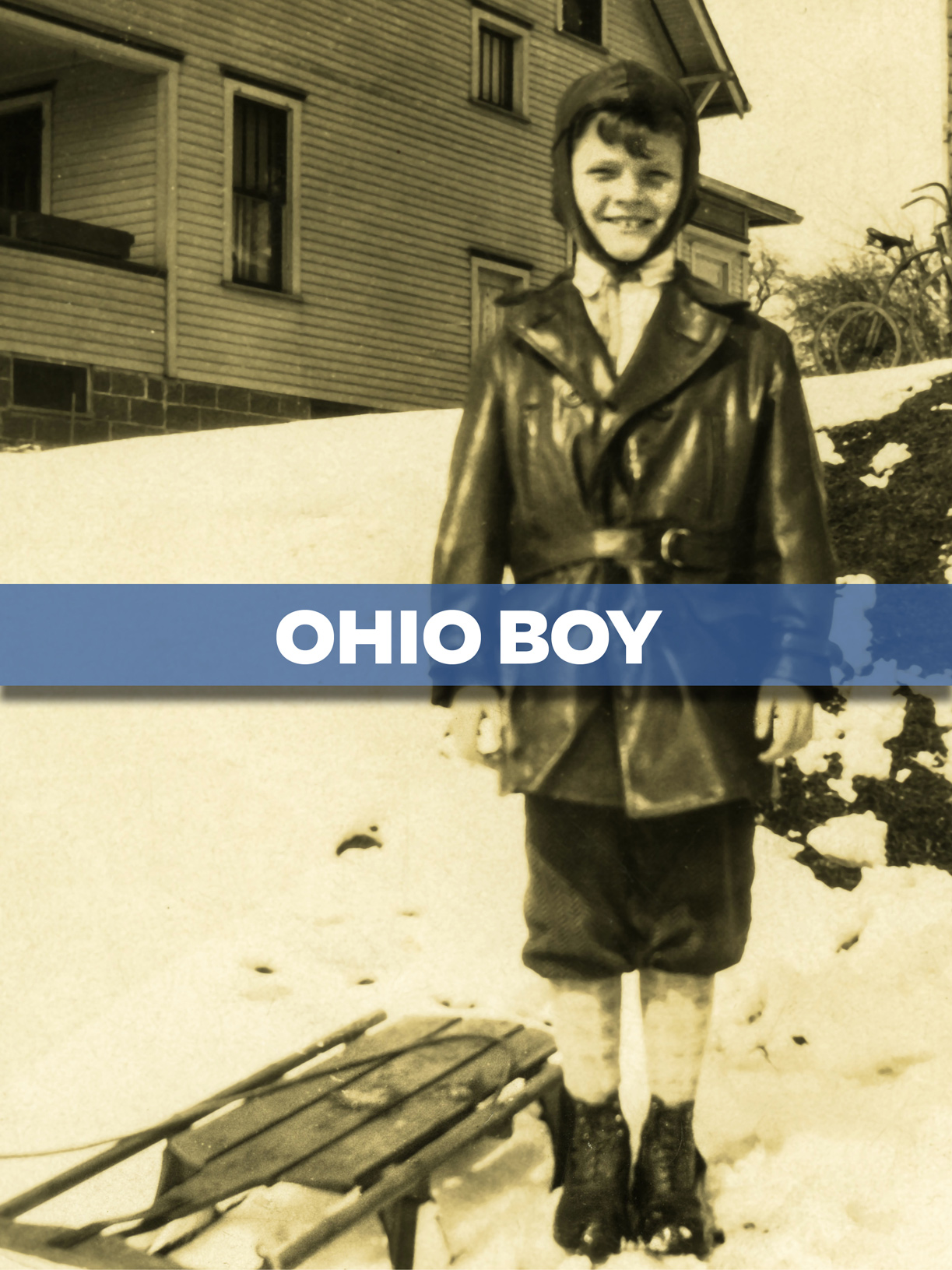

AN HOURS drive east of Columbus, Ohio, along what was once the pioneer route known as the Zanes Trace but is now Interstate 40, is the village of New Concorda place, John Glenn has said, that could have inspired Norman Rockwells paintings. In the nineteenth century Scotch-Irish farmers came here to settle the Ohio frontier. In 1923 it was where an apprentice plumber named John Herschel Glenn and his wife, Clara Sproat Glenn, came with their two-year-old son John Herschel Jr. They built a house at the towns western edge on a gravel road called Shadyside Terrace, where they rented rooms to students at nearby Muskingum College. The elder Glenn, who had a sixth-grade education, soon established his own plumbing company, which he built into a successful business.

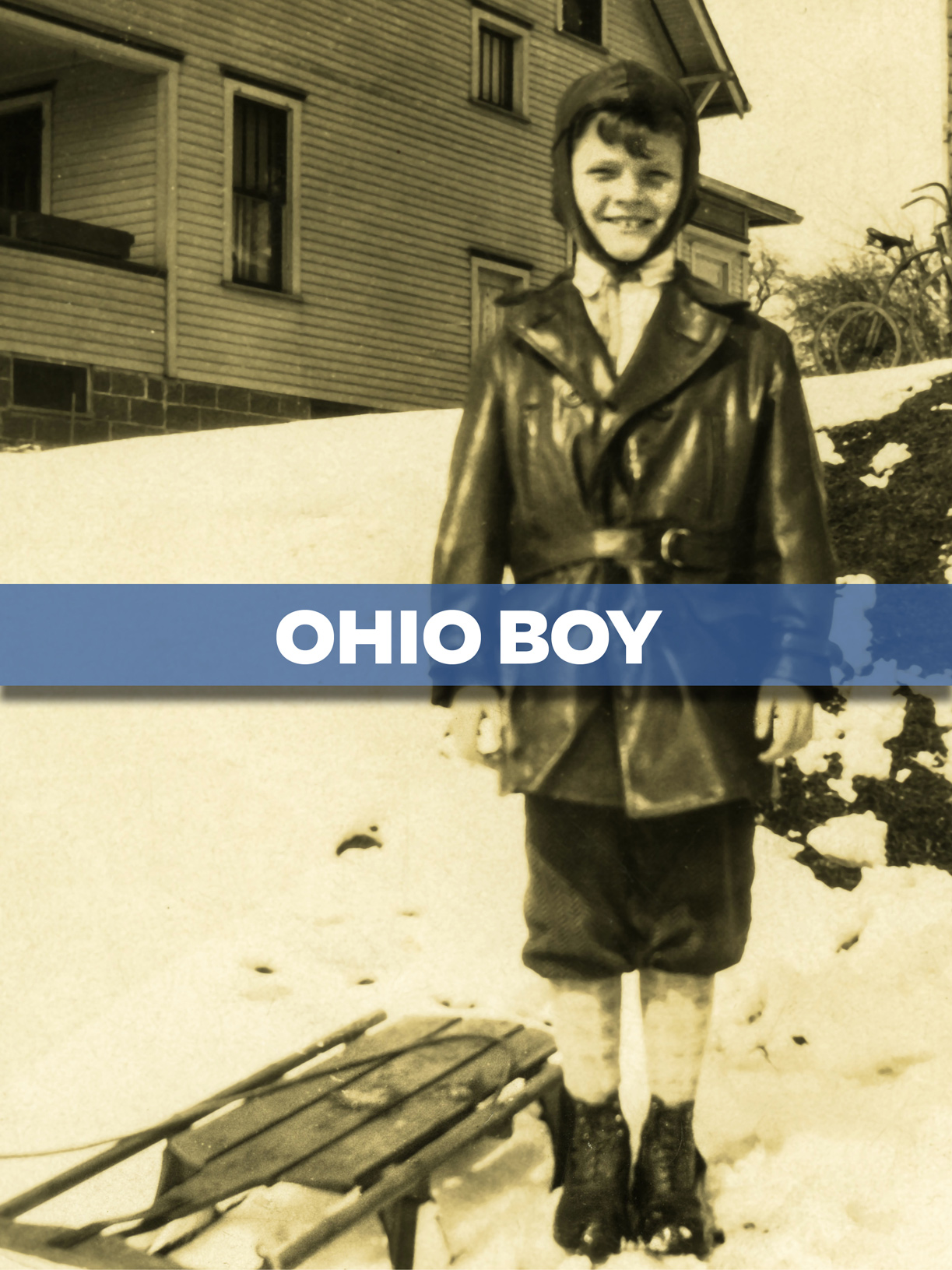

Growing up in a small townNew Concords population was around 1,100, not counting the thousand-odd students at Muskingum Collegewas an experience Glenn has called almost idyllic.In a place where doors were left unlocked, where everyone knew each other, and a kid had the run of the town, the young John Glennknown as Bud to distinguish him from his fathersoon gained a sense of independence and a confidence in his own abilities. Even though his hometown was only a mile across, to Glenn it felt like the center of the universe.

John Glenn around the age of two, circa 1923.

Patriotism was the norm in New Concord when I was growing up, Glenn told an interviewer in 1999. It wasnt something you had to be taught. On Decoration Day, and Independence Day, and Armistice Day, the towns main street would be lined with spectators for parading veterans, including Herschel Glenn, whod served in France in the First World War. After the parade, at a ceremony in the town cemetery, Herschel would play taps while young John, in the woods nearby, would play echoing phrases. For Glenn, the chance to play Echo Taps with his father, whom he called his hero, would become a powerful symbol of his towns devotion to American ideals.

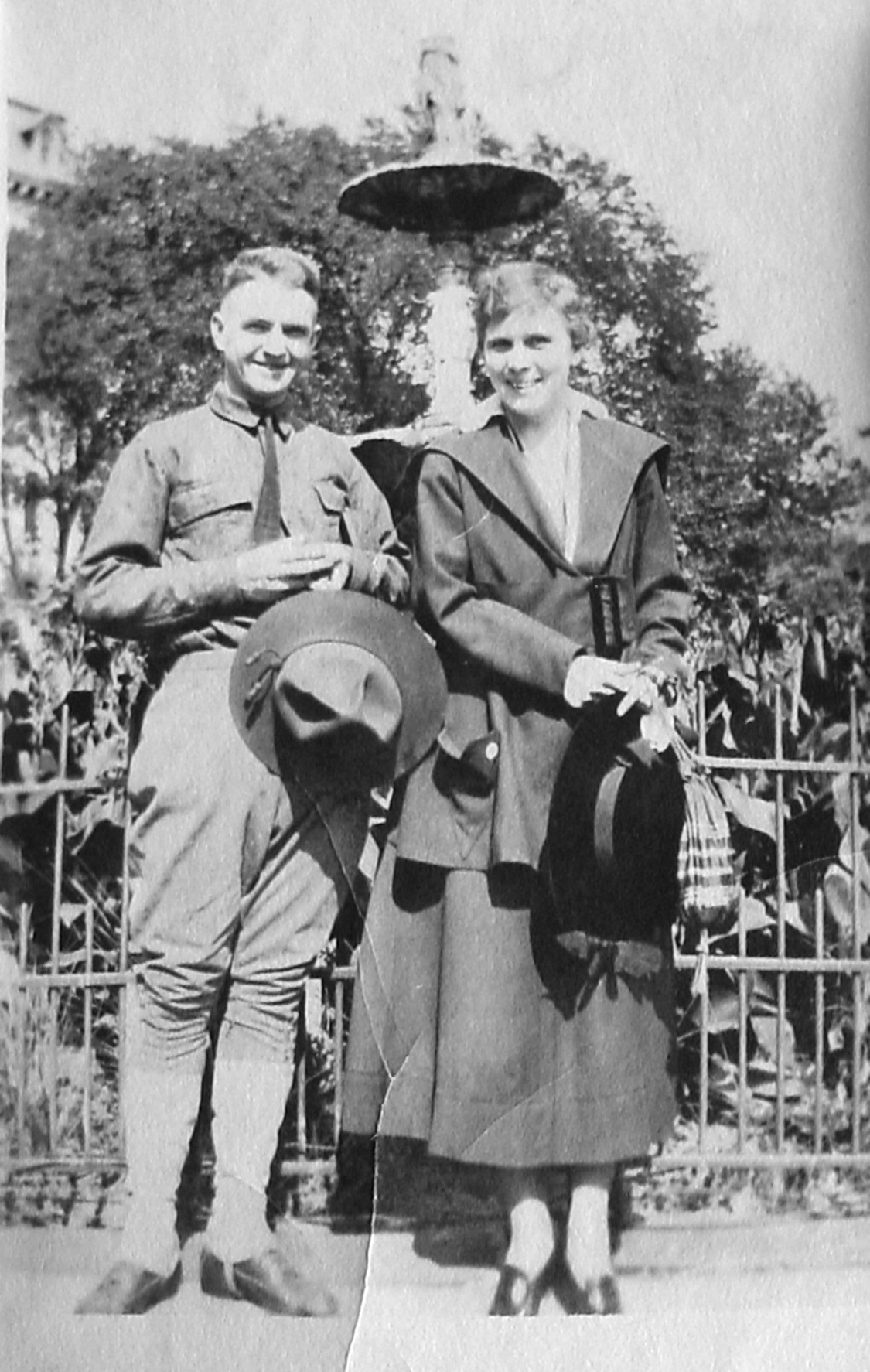

Glenns parents in 1918.

Only the Great Depression, which hit when Glenn was eight and his adopted sister Jean was three, clouded his bright childhood. One evening he overheard his parents talking about the possibility of losing their home, and he felt a stab of terror. As the hard times set in, work on the new gym at Muskingum College abruptly ceased, and the rusting metal-girder structure became part of the towns landscape. Families, including Glenns, turned spare land into gardens. Herschel Glenn took another job selling Chevys to make up for the lag in plumbing work. In time, New Concord weathered the Depression, aided by New Deal initiatives including a WPA effort to modernize the towns plumbing and sewers; Glenns father became a foreman on the project. His son never forgot the Depressions central lesson: Waste nothing.

Boyhood home outside New Concord, Ohio.

In the summer of 1929, in the last untroubled months before the stock market crash, Herschel Glenn asked eight-year-old John to accompany him on a drive to nearby Cambridge to check on a plumbing job. Along the way they passed a small airport and a grass field, where a pilot with an open-cockpit Waco biplane was offering rides. The boy could hardly believe it when his father suggested they go up together. From the back seat of the old Waco Glenn looked down at a world where everything seemed like props from a model train set. By the time the brief flight ended, Glenn was forever changed.