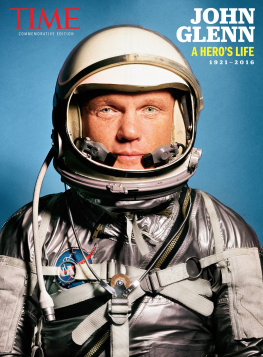

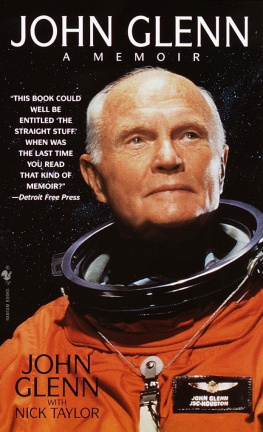

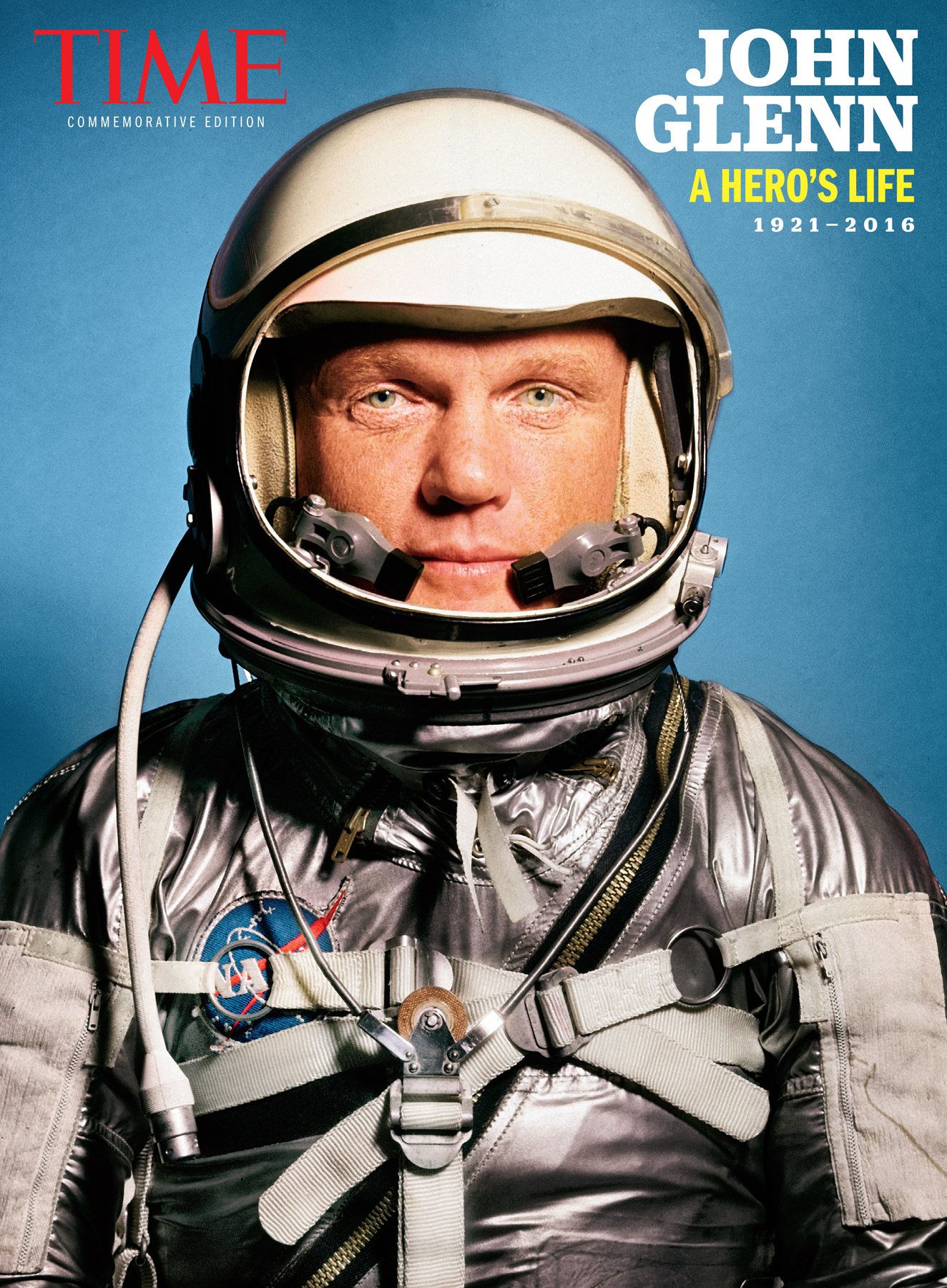

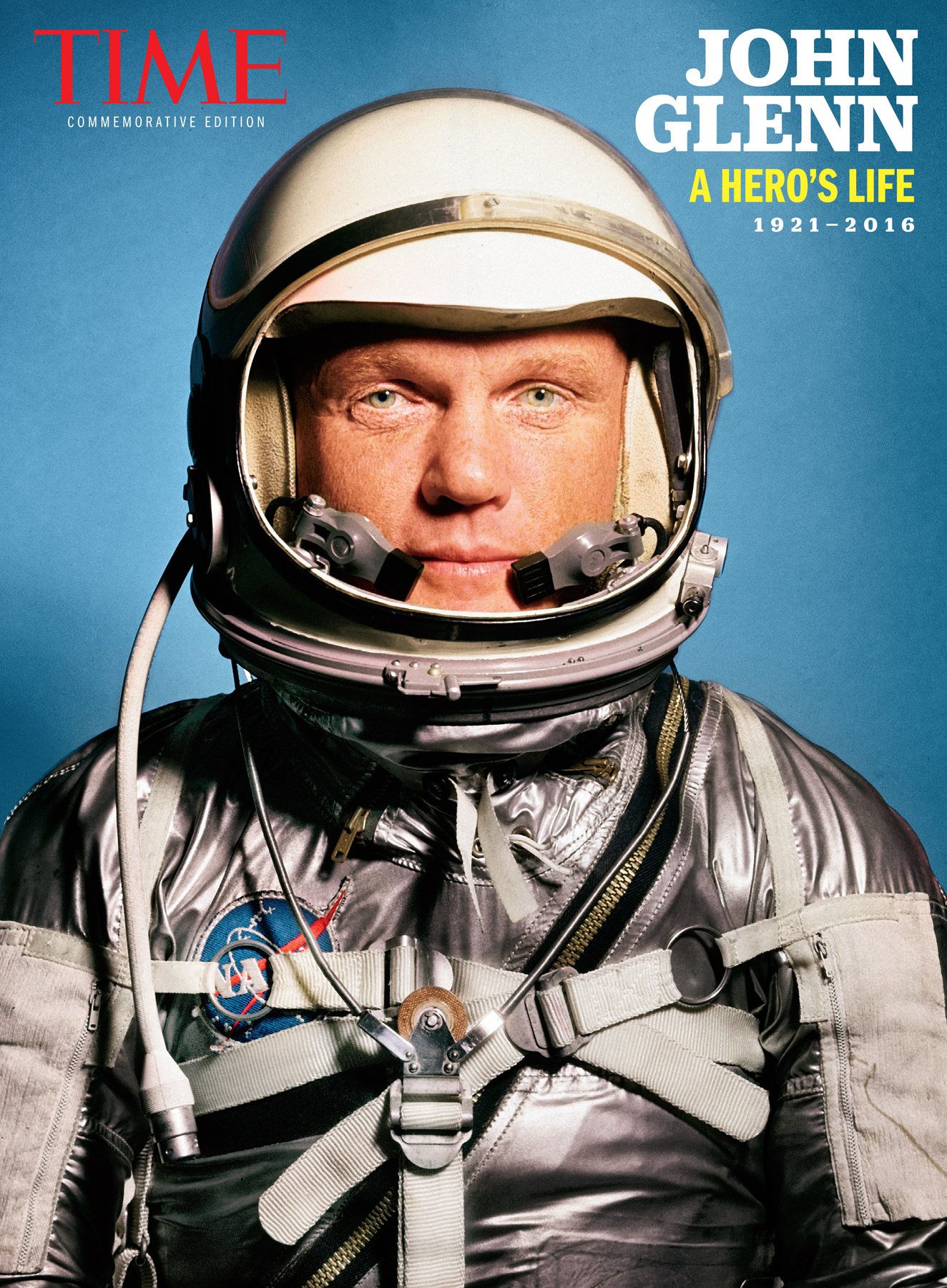

COMMEMORATIVE EDITION

JOHN GLENN

A HEROS LIFE

19212016

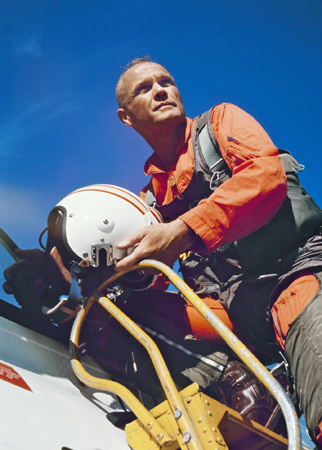

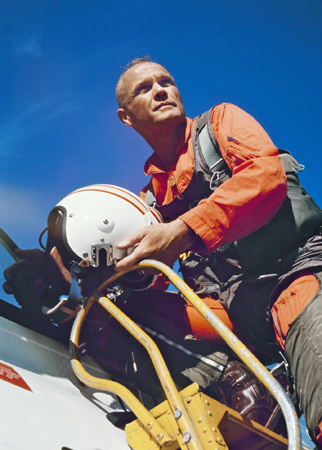

El Toro Marine Corps Air Station, 1964

LIFTOFF

The world watched as John Glenn launched in 1962, and TIME presented unparalleled coverage on the story

I. THE MAN

Clockwise from top left: John Glenn at four months old; Glenn, center, on the New Concord High School football team; Annie Castor and Glenn sit in his car, nicknamed the Cruiser, in 1938.

In his flight across the heavens, John Glenn was a latter-day Apollo, flashing through the unknown, sending his cool observations and random comments to Earth in radio thunderbolts, acting as though orbiting Earth were his everyday occupation. Back on Earth, Glenn seemed to be quite a different fellowan enormously appealing man, to be sure, but as normal as blueberry pie. He had an engaging, small-town charm, a sturdy character that was etched in the lines on his face, an attractive family and a deep faith in a power greater than I am that will certainly see that I am taken care of.

The homely, American Gothic image was an understatement of the real man, for John Glenn seemed almost destined for this time of triumph. All of his adult years he pursued the stars. As a test pilot and a combat flyer with 149 missions in World War II and Korea (he held six Distinguished Flying Crosses), Glenn had lived with supersonic speed and the constant possibility of sudden death. To the millions who saw and heard him, it was obvious that John Glenn was a perfect choice to become the first American to orbit Earth.

He was raised in New Concord (pop. 2,000), a quiet, shirt-sleeves-and-overalls town in central Ohio, where his father, by turns, was a railroad conductor, the proprietor of a plumbing business and the owner of the local Chevrolet agency. As a boy, Glenn swam in Crooked Creek, hunted rabbits, played football and basketball, read Buck Rogers, was a great admirer of the big-band musician Glenn Miller and blew a blaring trumpet in the town band. Predominantly Presbyterian, New Concord had a moral code that judged cigarettes to be instruments of the devil, and the kids nicknamed the town Saints Rest. But even for New Concord, young Glenns standards were strict.

When we were about 12, Johnny and I belonged to a group called the Ohio Rangers, recalls Rev. C. Edwin Houk, who went on to become a Presbyterian pastor in Glendale, Calif. We had taken a vow never to use profanity. One evening the group started singing Hail, Hail, the Gangs All Here. I continued with the phrase, What the hell do we care. Well, I can tell you, it didnt sit well with Johnny. He came up to me, white-faced and righteous, and told me to stop. I think he was ready to knock my block off.

In 1939 Glenn entered Muskingum College, a small Presbyterian school in New Concord. He was a substitute center on the football team, got solid B grades and schemed to get into the war as a pilot. He learned to fly in a Navy program for civilians at New Philadelphia, 35 miles away, then quit college as a junior to join the Navys preflight program. In 1943 he took the Navys option to join the Marine Corps and won his gold wings and gold second lieutenants bars. Then, resplendent in his dress blue uniform, he came back home to New Concord to marry Annie Castor, daughter of the town dentist, and his sweetheart ever since he could remember.

In World War II, Glenn flew 59 ground-support missions in the Pacifics Marshall Islands. After the war, he developed a cocksure method of demonstrating his flying skills. Says Marine Lt. Col. John Mason, Johnny would fly up alongside you and slip his wing right under yours, then tap it gently against your wingtip. Ive never seen such a smooth pilot.

In the Korean War, Glenn flew F9F Panther jets, again on ground-support missions. After going on several missions with Glenn, Ted Williams, the Red Sox left fielder recalled to duty as a Marine pilot, declared flatly, The man is crazy. Says Lt. Col. Edward Lovette, We called Glenn Ol Magnet Tail because his plane was hit so many times in combat.

Late in the war, Glenn got a chance to hunt the Soviet-built MIG-158 when he was assigned to fly Air Force F-86s up along the Yalu. Characteristically, Glenn was well prepared for the switch to F-86s: back in the States he had taken leave to learn how to fly the hot jet. In his plane, which was named the MIGMad Marine, Glenn got three MIGs in nine days. Funny how the bullets sparkle when they hit a plane, he wrote home after one victory. Just light up like little lights every time a bullet hits. Really had them pouring into it. Just chopped it up good until it flamed.

Ordered back to the U.S., Glenn ended up as a test pilot for the Navys Chance Vought F8U Crusader fighter. On one flight, Glenn showed the determination that would later land him in the cockpit of Friendship 7 to orbit Earth. He had the F8U up to Mach 1.2 when something snapped and the plane veered sharply. Most test pilots would have gingerly guided the plane back to the base, but Glenn, scribbling notes all the while, stubbornly pushed the fighter up to Mach 1.2 twice more to see if it would happen again. It did. When he finally landed, Glenn discovered that 24 feet of the trailing edge of a wing had broken off.

Early in his career, Glenn developed the art of sniveling. Explains Marine lieutenant colonel Richard Rainforth, who flew beside Glenn in both World War II and Korea, Sniveling , among pilots, means to work yourself into a program, whether it happens to be your job or not. Sniveling is perfectly legitimate, and Johnny is a great hand at it. In 1957 Glenn sniveled the Marines into letting him try to beat the speed of sound from coast to coast. Flying an F8U, Glenn failed by nine minutes, but he did knock 23.5 minutes off the coast-to-coast speed record by covering the distance in three hours and 23 minutes at an average speed of 726 mph.

Then, in 1959, Glenn resolutely set out to snivel his way into the toughest program of all: Project Mercury, the nations spaceflight program. He started with two handicaps: he lacked a college degree, and, at 37, he was considered an old man. But Glenn managed to get permission to go along as an observer with one prime candidate from the Navys Bureau of Aeronautics. When the candidate failed an early test, recalls Rainforth, Johnny stepped up, chest high, and offered himself as a candidate. They took him.

Candidate Glenn and more than 500 others were run through a wringer of mental and physical tests. Doctors charted their brain waves and skewered their hands with electrodes to pick up the electrical impulses that would tell how quickly their muscles responded to nerve stimulation. Glenn held up tenaciously under tests of heat and vibration and did especially well with problems of logical reasoning. Says Stanley White, a Project Mercury physician, Glenn is a guy who lives by facts.

To the surprise of no one who ever knew him, Glenn was one of the seven former test pilots who were picked to become the nations first astronauts. But even among the astronauts, John Glenn stood out in his determination. By his own decision, Glenn spent only weekends with his family in Arlington, living Monday through Friday at Virginias Langley Air Force Base so that he could better concentrate on the program. He ran two miles before breakfast every morning, sweated himself from 195 pounds down to a flat-bellied 168.

Next page