Copyright 2020 by Working Teitel, Inc.

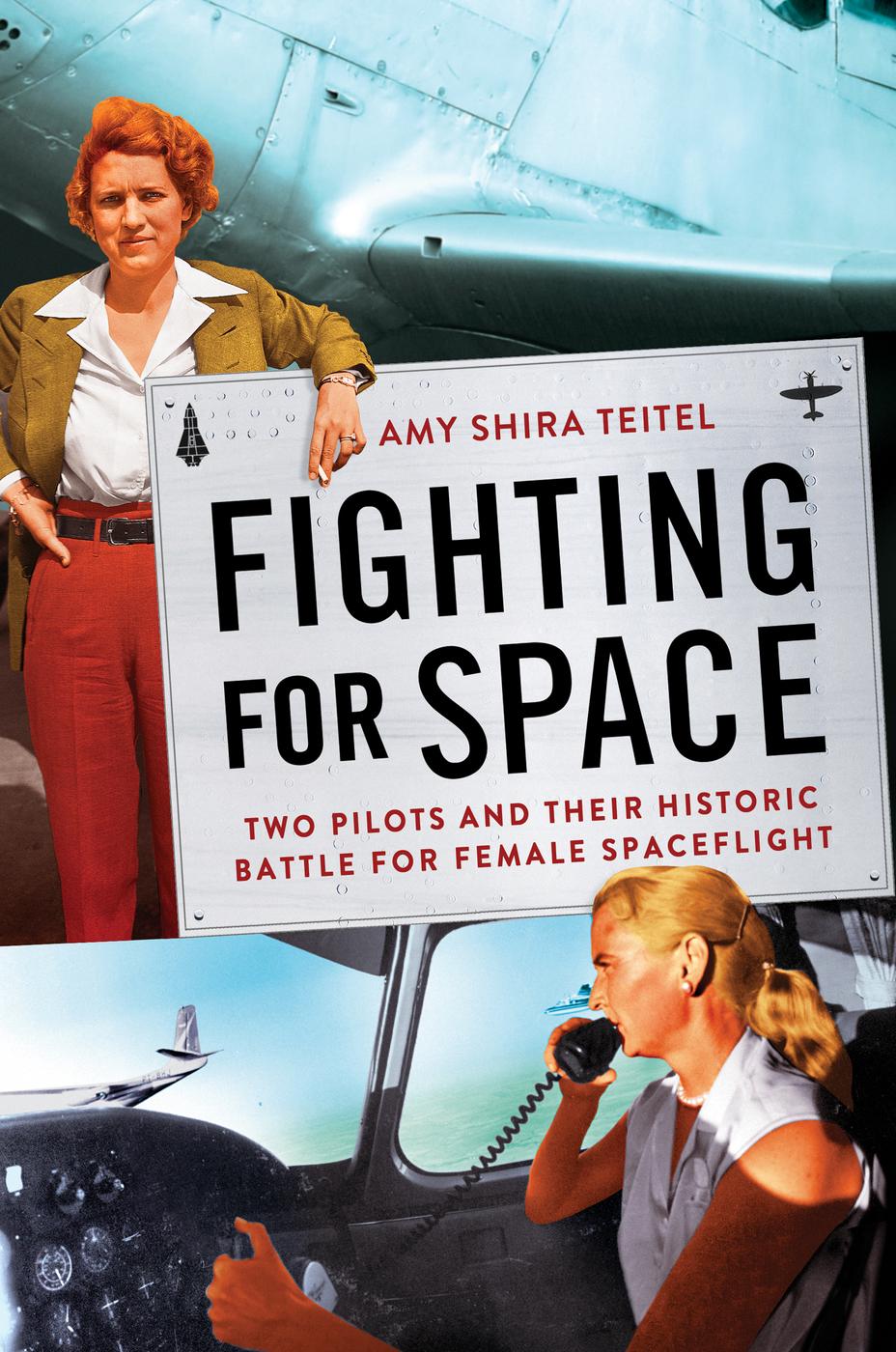

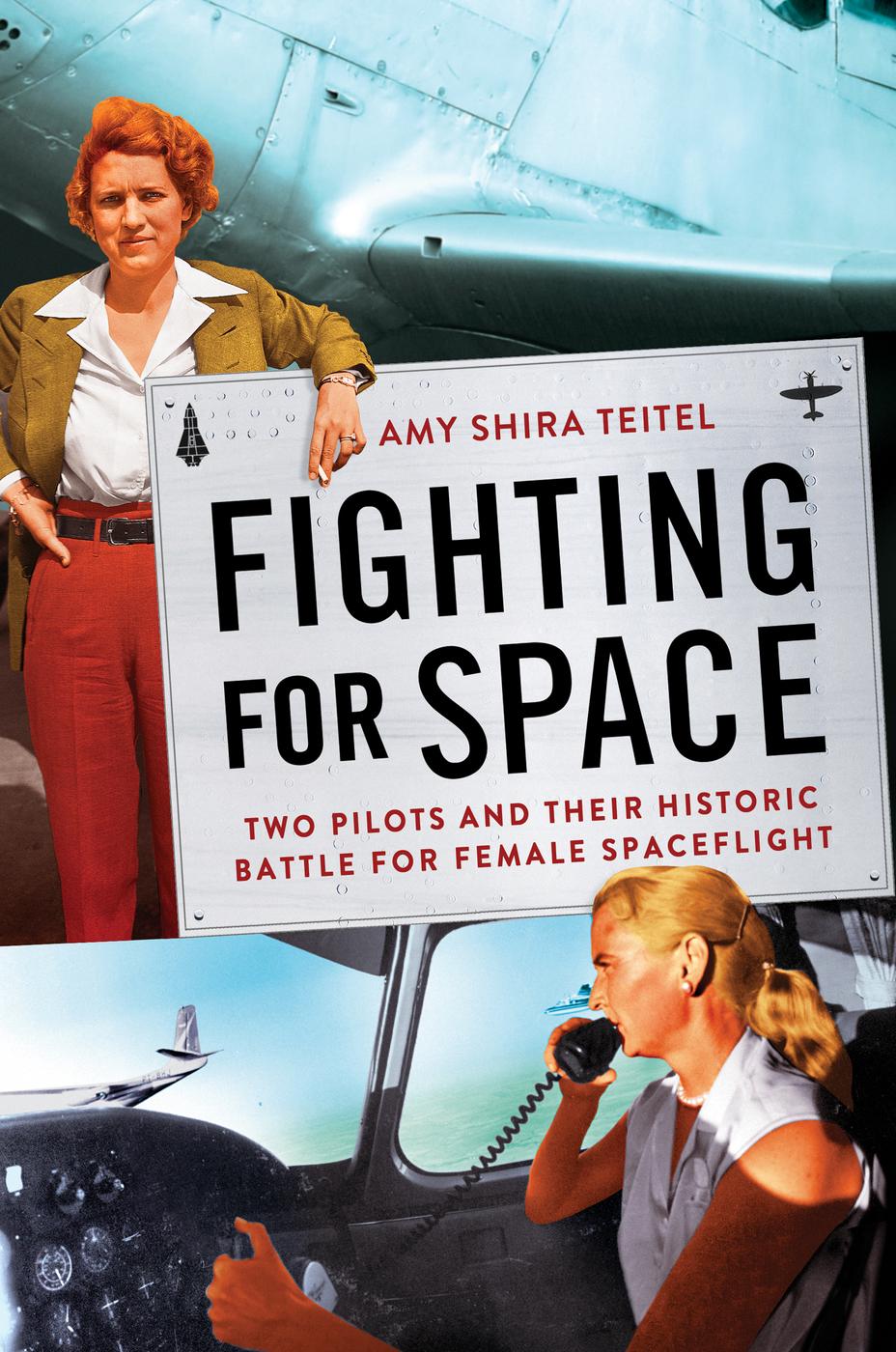

Cover design by Phil Pascuzzo. Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

grandcentralpublishing.com

twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First Edition: February 2020

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Material from John Glenn: A Memoir by John Glenn with Nick Taylor, copyright 1999 by John Glenn, used by permission of the authors estate.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBNs: 978-1-5387-1604-5 (hardcover), 978-1-5387-1603-8 (ebook)

E3-20200127-DA-NF-ORI

E3-20191118-DANF-ORI

For women everywherepast, present, and futurewho stand their ground when they know theyre right. You inspire more people than you realize.

And for Jackie. Its time the world remember you.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

The first half of the twentieth century was an interesting time for America.

Our story starts in 1912, the year the Titanic sank while carrying more than 2,200 people from England to New York. Steamships and other boats were the only way people could cover vast oceanic distances. There were no transatlantic flights; airplanes were fodder for the rich and daring to soar moderately high above a gathered crowd for minutes at a time.

The First World War changed that. Aerial officers flew ahead of soldiers on foot to get the lay of the land, then they carried guns as protection, and finally, those guns were fixed to the front of the planes. A pilot could aim his gun by aiming his aircraft, relying on an interrupter gear to ensure the propeller blades never got in the way of automatically firing bullets. Wood and fabric fuselages soon gave way to all-metal vehicles, and by the end of the war pilots routinely engaged in swirling aerial dogfights. For civilians, these stories imbued flying with unparalleled excitement and a feeling the future was right over the horizon.

As these high-performance planes became available to private pilots, the Everyman took a step closer to the sky. Aviators dazzled audiences with aerial displays. Sometimes, lucky onlookers could even take a ride in a plane, either at a county fair or at a small airport that offered rides for a small fee. Flying held allure. It was romantic, thrilling, dangerous, and the pilots who flew were like no one else on Earth.

Coincident with the end of the First World War was the first wave of feminism; suffragettes fought for equality and won women the right to vote in 1920. Women had freedoms theyd never known, a change in status that saw echoes in fashion and culture. Women eschewed restrictive clothing in favor of skirts and trousers that offered physical freedom. In this newly emancipated climate, women took to the sky, though this wasnt without challenges. Few men would consent to teach women to fly, and even fewer would take on African American students. When Bessie Coleman decided she wanted to earn her pilots license, she had to train in France, where she met no racial barrier in getting a license. When she returned to America in 1921 at the age of twenty-nine, she was greeted with press coverage and enthusiastic audiences. Female aviators held a different appeal; if men flying was exciting, women flying was a novelty like no other. The sky was starting to open to women.

Regardless of gender, flying had the power to turn everyday people into heroes, and no one embodied this phenomenon as completely as Charles Lindbergh. After he made the first solo flight across the Atlantic, he went from unknown air mail pilot to celebrity overnight. When Amelia Earhart became the first woman to cross the Atlantic in a plane, her fame similarly skyrocketed even though she was merely a passenger on that flight. Regardless, women watching these feats were inspired to follow suit, and by 1929 there were ninety-nine licensed women pilots of all backgrounds in the United States. That same year, Amelia was a founding member of an all-female flying society called the Ninety-Nines, which is still active today.

As the United States sank into the Depression in the 1930s, women working became increasingly commonplace. Wives, mothers, and daughters did their part to help their families escape the poverty that touched nearly every corner of the country. For the women who could afford luxury activities in the period, flying became more popular; by the end of the decade, there were more than 500 licensed women pilots in the country. Womens independent streak was mirrored in pop culture. Fictional heroines, even in love stories, were often defined by their jobs and passions as much as their womanhood. Take Rosalind Russell (a friend of our heroine Jackie, whom youll meet in a moment) in His Girl Friday (1940). Rosalind is prepared to quit her job as a reporter to marry Ralph Bellamy and enjoy the domesticity that comes with married life. But her boss and ex-husband Cary Grant (another acquaintance of Jackies) isnt prepared to let her go. So he woos her, not with the promise of a big house and children but with a story of an escaped accused murderer she cant resist covering. Rosalind isnt just a woman, shes a hard-hitting reporter, and thats what Cary loves most about her.

The Second World War brought new opportunities for women. As men went off to fight, women took their places in factories earning the same pay as their male counterparts. Military programs gave women more immediate ways to serve their country. The Army Air Force had the WASPs (Womens Auxiliary Service Pilots), the Navy had the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), and the Army had its WACs (Womens Army Corps). For the first time since the Civil War, American women could earn military recognition. They took pride in their work, and almost all hoped their independence would persist after the wars end.

But the same government that made Rosie the Riveter a wartime icon for working women put her in the kitchen in the 1950s. After decades of upheaval from the Depression and Second World War, postwar America focused on family values, and government propaganda campaigns followed suit. God was added to currency and the Pledge of Allegiance. A womans role was now that of wife and mother with ideals of womanhood wrapped up in her biology. The postwar woman married younger and had more children. Her home was her castle, equipped with appliances to free her from the drudgery of cleaning, television for entertainment, and the PTA as a social outlet. Fictional women changed, too. Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell in