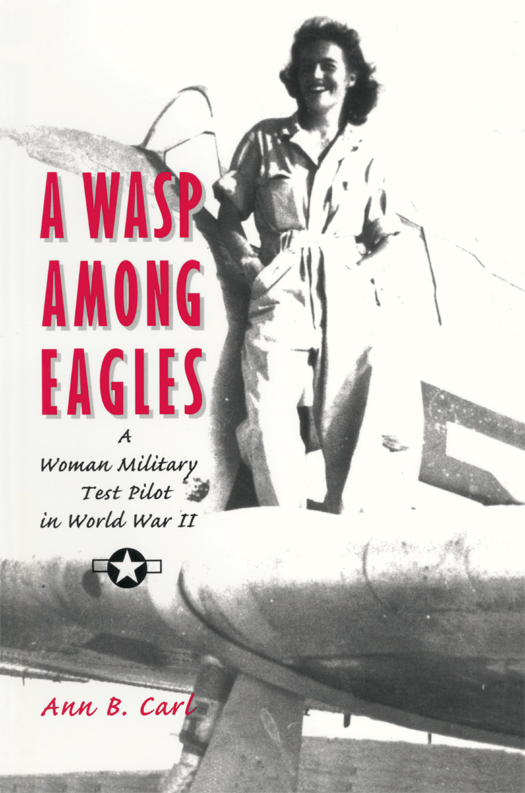

Ann Carl in her WASP uniform.

1999 by Ann B. Carl

All rights reserved

Copy editor: Initial Cap Editorial Services

Production editor: Ruth Spiegel

Designer: Martha Sewall

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Carl, Ann B. (Baumgartner)

A WASP among Eagles : a woman military test pilot in World War II / Ann B. Carl.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Carl, Ann Baumgartner 2. World War, 19391945Aerial operations, American. 3. World War, 19391945Personal narratives, American. 4. Women Airforce Service Pilots (U.S.)Biography. 5. Women air pilotsUnited StatesBiography. 6. Women test pilotsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

D790.C272 1999

940.544973082dc21 98-39772

eISBN: 978-1-58834-341-3

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works as listed in the individual captions. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these illustrations individually or maintain a file of addresses for photo sources.

v3.1_r1

Contents

ContentsA winged steed, unwearying inflight,

Sweeping through the air swift as a gale of wind.

HESIOD , The Catalogue of Women

DEDICATION AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book deals with a particular time in World War II history and involves real people, many of them well known, even famous. Realizing the grave responsibilities in presenting them in my narrative, I have described them as I knew them. What they say and do in this book is based on my recollection of day-to-day contact with them, on old letters, and on more recent conversations. And to them all, this book is dedicated.

My account of flight testing at a time when the speed of sound was a barrier to overcome on the way to greater speed of aircraft might never have been written without the impetus and encouragement of these people: Ethel Finley, president, WASP (Women Airforce Service Pilots), 199294; Dr. R. R. Gilruth of the NACA (later NASA); Maj. Kenneth Rowe, Administrator of Aviation (Ret.), Commonwealth of Virginia; John Tebbel, historian, and Col. Nathan Rosengarten, chief of Flight Research, Wright Field Air Force Base.

Along the way, NASA historian Deborah Douglas contributed discerning and helpful suggestions. And my editor and literary agent, William B. Goodman, always professional and tactful, kept me squarely on the road through dark valleys of discouragement and ephemeral highpoints. With expertise, Ruth Spiegel, production editor at the Smithsonian Institution Press, and copyeditor Therese Boyd prepared the book for publication.

My husband, Bill, besides being part of the story, suffered through my solitary throes of creation and then carefully (and kindly) checked my facts and helped clarify my technical explanations.

INTRODUCTION

During the 1990s controversy over whether or not women should fly military aircraft in combat, it was suddenly brought to light that 50 years earlier a thousand women were quietly flying Air Force military aircraft of all kinds. Their job had been to release men for combat in World War II while they, as it were, took care of home-port flying.

Oddly enough, the permission for combat granted to the 1990 women flyers became overshadowed by a frenzy for celebrating those forgotten ladies of the misty past of the 1940s. They had no publicity at the time. In fact, they had very little status. They served as Civil Service personnel attached to the Army Air Forces. It was not until 1977, thanks to Sen. Barry Goldwater among others, that legislation was finally passed making them full-fledged members of the Air Force.

These were the WASPsWomen Airforce Service Pilots. Without fanfare, they served in World War II from 1942 to 1945. In December 1944, the WASPs were disbanded, and, except among themselves, forgotten.

Already licensed pilots, they had been recruited by famous aviators Nancy Love and Jacqueline Cochran, who had persuaded Gen. H. H. Hap Arnold that experienced women pilots could take over flying jobs at home. About two dozen of the most experienced (with over 500 hours of flying time) were sent to England immediately to assist the womens Air Transport Auxiliary of the RAF. Another dozen were assigned to the U.S. Air Transport Command to ferry new aircraft then flowing from production lines to U.S. bases and export points. (Contrary to some reports, the WASPs did not fly bombers transatlantic to England.)

To keep the supply of women coming, Jackie Cochran organized a training program that followed exactly the Air Force cadet program of primary, basic, and advanced flight training and ground school. Even the training aircraft were the same. Although 25,000 women applied, only 1,800 were selected and of these only about 1,000 received their wings. Thirty-eight lost their lives while in service.

Women came from every kind of occupationfrom bartender to physician, from journalist to actressbut all of them became capable, patriotic members of the Air Force flying community. And many had family members in service as well. These women flew every kind of Air Force plane. Most ferried planes to bases. Others towed targets for artillery gunners, some were instructors, some flew special planes. In fact, they flew, without regard to risk, whatever they were asked to fly. They did not, however, aspire to fly in combat overseas.

The years 199395 have been celebrated as the fiftieth anniversary of the WASPs. They have been sought out, individually and en masse, to speak and be on display. Uniforms have been brought out of mothballs and the stories of their wartime derring-do have at last been told.

I have a unique addendum to this story, and I have been urged by many people and organizations to set it down. Quite simply, as an experimental test pilot with the Air Force, I flew our first jet fighter and, in fact, became the first woman to fly a jet aircraft. That was in October 1944. I was on a special assignment to Wright-Patterson Air Force test center, where all experimental aircraft were rigorously evaluated before acceptance by the Air Force and where these aircraft were also tested against captured enemy aircraft. There was danger involved, and the pilots here were either seasoned combat pilots or aeronautical engineers, often both. They were head of the class of the Air Force, as Wright Field was the heart of the Air Force. To be assigned to work with these pilots was indeed a privilege.

Although I am basically more interested in writing about others (after the WASPs were disbanded, I joined the Wright Field public relations department to write news stories about the test-pilot heroes), I have been persuaded that it is important that this special and intriguing WASP tale be told. Therefore, in this short book, I have tried to explain (people have asked) how I happened to fly in the first place, what it was like to be on this separate assignment, and what it led to.