An Eagles Odyssey

This edition published in 2019 by Greenhill Books

c/o Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley,

S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Publishing History

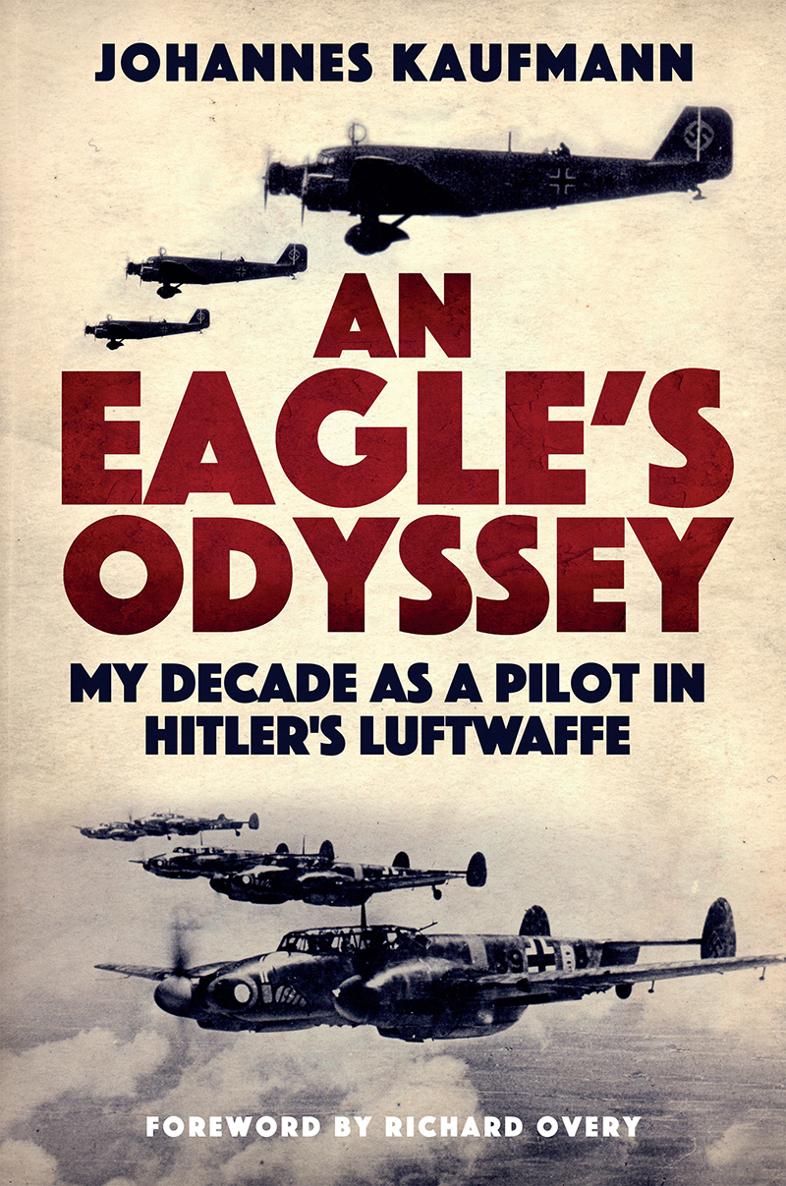

Johannes Kaufmanns Mein Flugberichte 1935-1945 was first published by Journal Verlagshaus Schwend in 1989. This is the first English language translation and includes a new foreword by Richard Overy.

www.greenhillbooks.com

Greenhill Books ISBN: 978-1-78438-253-7

eISBN: 978-1-78438-278-0

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-78438-279-7

All rights reserved.

Main text Johannes Kaufmann, 1989

English language translation John Weal, 2019

Richard Overy foreword Greenhill Books, 2019

Front cover image colourised by Jon Wilkinson

The moral right of Johannes Kaufmann,

has been asserted in accordance with Section 77

of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

Foreword

Captain Johannes Kaufmann was a lucky man. Where thousands of German pilots perished in combat or accidents over the wartime years, Kaufmann survived some 212 combat operations, a number of years as a Luftwaffe instructor, and numerous ferrying and test flights, often in atrocious weather. His luck held throughout this tenyear Eagles Odyssey, from his first training flights in 1935 as a novice twenty-year-old, to his last operation escorting suicide aircraft in April 1945, flown by pilots who, unlike Kaufmann, embraced death rather than defeat.

Survival was a lottery in every air force, but it is clear from Kaufmanns account that it was not just luck. He was evidently an outstanding pilot, utterly at home in the cockpit and able on numerous occasions, detailed throughout his autobiographical account, to extricate himself from crisis after crisis. These qualities picked him out as a natural instructor and most of the first half of his career as a pilot in the Luftwaffe was spent training others to the same high technical and practical standards he set himself. As a result, he did not see his first combat operation until June 1941 when as a re-trained heavy-fighter pilot flying the Messerschmitt Bf 110 he took part in the opening months of the German Barbarossa campaign against the Soviet Union.

It is here that his account really comes to life. He recalls that his years as an instructor were fulfilling enough but lacked the excitement and challenges of combat. His narrative of life as a junior Luftwaffe pilot spans the whole story of Hitlers war from the ground-support operations in 1941 to help the German Panzer forces rout the Red Army, to the final desperate effort to stem the remorseless bomber offensive, when as a squadron commander he took off day after day knowing that this might well be his last mission. In the interval he flew at Stalingrad, engaged in maritime operations with Kampfgeschwader 40, based in western France, returned to Germany to be trained in turn as a single-seat fighter pilot, followed by action at Arnhem, during the Battle of the Bulge, and in the doomed effort to stem the tide of Soviet advance on Berlin. Kaufmanns often vivid recounting of flights and operations will appeal to everyone with a desire to understand just what it was like to fly mission after dangerous mission.

Several things stand out from what is a simple and straightforward account by an ordinary pilot of the revival and decline of German air power in the 1930s and 1940s. Kaufmann provides a good deal of background detail on what life in the air force was like, from the accommodation (lavish by most standards in the new air force quarters built in the 1930s, Spartan once in the field), the food (he almost never complains of being hungry), to the schedules and curricula of the various training stations where he both learned and taught the art of flying. He is unstinting in his praise of the ground crews, that essential branch of the air force that kept aircraft in good shape, repaired damage in a day or less, and coped with the shrinking supply of spare parts. He is much less enthusiastic about his superiors who often failed at briefings to provide pilots with full or precise instructions, gave haphazard meteorological information, and then complained at debriefing if the crews had not achieved what they were intended to.

The second striking feature of Kaufmanns story is the extent to which the Luftwaffe improvised or cut corners to cope with the numerous demands created by Hitlers strategy. The peripatetic career that Kaufmann himself enjoyed, switching from one kind of aircraft to another, moving from front to front seemingly at random, is testament to just how difficult it was for the Luftwaffe to cope with multiple demands for ground-support, counter-force operations, maritime air warfare and defence against bombing. Kaufmanns own judgement, seen from the worms eye view, was that better use might have been made of what air resources were available. When he was switched to a ground-support role in Russia he had had almost no experience, received quite inadequate training, and like many others developed his tactical skills and operational awareness in the harsh apprenticeship of combat. Improvements in tactical behaviour seem often enough to have been the fruit of post-operation discussions between the pilots themselves rather than directed from above. Luckily for him, Kaufmann was a quick learner so that the move from one aircraft type to another did not affect him much. He even flew in a unit designed to test and then adopt the ill-fated Me 210 replacement for the ageing Bf 110, an aircraft in which a good many pilots died because of poor handling qualities. Kaufmann flew the aircraft without incident though he does judge it here to have been a design disaster. He ended up flying the Messerschmitt Bf 109, but proved just as adept as a single-engine fighter pilot as he had been on the heavy twin-engine Bf 110, though by late 1944 he reckoned the latest Spitfire mark to be a much superior aircraft.

The most curious aspect of this autobiography is the almost complete absence of the wider world in which he lived and operated. A reader might be forgiven for not realizing that Kaufmann served one of the most brutal dictatorships of the twentieth century. He even records a flight over the village of Dachau in 1936 with no mention of the camp that lay below him. Kaufmann himself notes that he and his companions knew it was prudent to keep our views on current events to ourselves, but even then it is hard to believe that he was not aware of or affected by the existence of the states repression or, in service on the Eastern Front, that he saw nothing of the atrocities performed all around him. His account fits perfectly with the image of the clean Wehrmacht, which was strongly defended in the first decades after the end of the war in 1945. But his memoir, first published in 1989, came at just the time that German historians were scrutinizing the archive to discover how compromised the German armed forces were in undertaking routine atrocities and assisting the genocide of the Jews. Only a few years later a major exhibition was mounted on the Crimes of the Wehrmacht which prompted a harsh public debate about the extent to which German servicemen either aided or knew about the criminal activities on the Eastern front. Kaufmanns account would have added grist to the mill of those who argued that most of the Wehrmacht was innocent of the crimes committed in the East and elsewhere. It is true that Kaufmann may well not have witnessed anything himself, but rumour was rife among those serving in the East. He clearly made the decision when he wrote his memoir to remain prudent when it came to commenting on anything but his flying. The one time he steps out of this mould is his account of a visit to a Hitler speech in 1942. It was, he records, a three-hour monologue but he sat with rapt attention. He seems to have been too nave to realize that this was not a very prudent admission for his postwar audience.