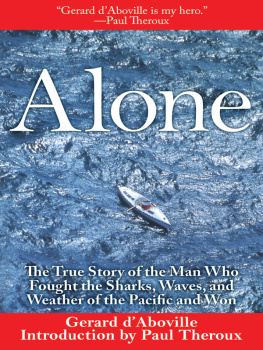

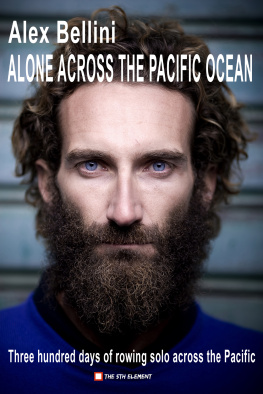

Alone

Alone

The True Story of the Man Who Fought the Sharks,

Waves, and Weather of the Pacific and Won

Gerard dAboville

Translated from the French by Richard Seaver

Introduction by Paul Theroux

Copyright 1992, 2011 by Editions Robert Laffont, S. A. Translation copyright 1993, 2011 by Richard Seaver Introduction copyright 1993, 2011 by Paul Theroux

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books maybe purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-112-2

Printed in the United States of America

Of all the creatures on the face of the earth, humans are those who adapt most easily, not only to the most extreme temperatures and climates but also to the most arduous conditions that life imposes on them.

Henri de Montfried

To these words I would simply like to add that humans derive this capacity to adapt through a characteristic that is theirs alone: the ability to dream and to hope.

I dedicate this book to all those men and women for whom this adventure this ocean voyage may serve to rekindle in their hearts a spark of hope.

Gerard dAboville

Contents

I would like to thank the friends, colleagues, and business associates who helped make this adventure possible:

Sector Sport Watches Transpac Accastillage Diffusion Air France Air France Cargo P.L.B, Capitarne Cook Eurest Go Sport P.N.B.

as well as:

Audiophase All Nippon Airways Jean Barret B.N.P. Issy-les-Moulineaux Cabinet de Clarens Le Cercle de la Mer in Paris Le Borgne Navy Yard B. & B. Navy Yard The Hydro Technique Company C.R.M, Damart Dif Tours Elite Marine Fdration francaise des industries nau-tiques F.F.S.A. France Info Garage Arcillon Garbolino Hertz Hesnault International Airfreight Services Co. J.C.D, Ken Club Lestra Sport Lyophal Mat Equipement Mecanorem Nautix Neste O.I.P. Plastimo Port de Plaisance La Trinit-sur-Mer Ramtonic Regma Systmes Sail France Semari Socit Ono Sofomarin Sony T.B.S. 3 M Transparence Production U.S. Coast Guard Veillet International The City of Issy-les-Moulineaux

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The French Embassy in Tokyo The French Consulate in New York The French Consulate in San Francisco Tokyo Power Squadron Astoria Maritime Museum

Laurent de Bartillat Charlie Cronheim Commander Blan-villain Eddy Zimansky and his YL Georges de Marrez Dr. Chauve Olivier de Kersauson John Oakes Bruno de La Barre

Christophe Louis-Nol Claude Arnoult Jean-Claude Dufour Thomass Scooter Benoit and Philippe Beatrice Pierre Yvan Didier and Franois Moze Mr. and Mrs. Takasse Yagi Mitsuru Charles and Thibault Laurence and Franois Raymond Philippe Renaud Sophie Arnaud Vincent Nathalie the wonderful, and so many others

And Cornelia, for her patience

When my French publisher, Robert Laffont, asked me whom in the whole of France I wished to meet I said, DAboville, whose book Seul (Alone) had just appeared. The next day at a caf in the shadow of Saint-Sulpice, I said to dAbovilles wife, Cornelia, He is my hero. She replied softly, with feeling, Mine, too.

It is a commonplace that almost anyone can go to the moon: you pass a physical and NASA puts you in a projectile and shoots you there. It is perhaps invidious to compare an oarsman with an astronaut, but rowing across the Pacific Ocean alone in a small boat, as the Frenchman Gerard dAboville did in 1991, shows old-fashioned bravery. Yet even those of us who go on journeys in eccentric circles, simpler and far less challenging than dAbovilles, seldom understand what propels us. Ed Gillet paddled a kayak sixty-three days from California to Maui a few years ago and cursed himself much of the way for not knowing why he was making such a reckless crossing. Astronauts have a clear, scientific motive, but adventurers tend to evade the awkward questions why.

DAboville was forty-six when he single-handedly rowed a 26-foot boat designed especially for this unique voyage from Japan to Washington State in 1991. He had previously (in 1980) rowed across the Atlantic, also from west to east, Cape Cod to Brittany. But the Atlantic was a piece of cake compared with his Pacific crossing, one of the most difficult and dangerous in the world. For various reasons, dAboville set out very late in the season and was caught first by heavy weather and finally by tumultuous storms 40-foot waves and 80-miles-per-hour winds. Many times he was terrified, yet halfway through the trip which had no stops (no islands at all in that part of the Pacific) when a Russian freighter offered to rescue him, I was not even tempted. He turned his back on the ship and rowed on. The entire crossing, averaging 7,000 strokes a day, took him 134 days. I wanted to ask him why he had taken this enormous personal risk.

DAboville, short and compactly built, is no more physically prepossessing than another fairly obscure and just as brave long-distance navigator, the paddler Paul Gaffyn of New Zealand. Over the past decade or so, Gaffyn has circumnavigated Australia, Japan, Great Britain, and his own New Zealand through the low pressure systems of the Tasman Sea in his 17-foot kayak.

In a memorable passage in his book, The Dark Side of the Wave, Gaffyn is battling a horrible chop off the North Island and sees a fishing boat up ahead. He deliberately paddles away from the boat, fearing that someone on board will see his flimsy craft and ask him where he is going: I knew they would ask me why I was doing it, and I did not have an answer.

I hesitated to spring the question on dAboville. I asked him first about his preparations for the trip. A native of Brittany, he had always rowed, he said. We never used outboard motors we rowed boats the way other children pedaled bicycles. Long ocean crossings interested him, too, because he loves to design highly specialized boats.

His Pacific craft was streamlined it had the long seaworthy lines of a kayak and a high-tech cockpit with a roll-up canopy that could seal in the occupant in rough weather. A pumping system, using seawater as ballast, was designed for righting the boat in the event of a capsize. The boat had few creature comforts but all necessities: a stove, a sleeping place, roomy hatches for dehydrated meals and drinking water. DAboville also had a video camera and filmed himself rowing, in the middle of nowhere, humming the Alan Jackson country-and-western song Here in the Real World, DAboville sang it and hummed it for months but did not know any of the words, or indeed the title, until I recognized it on his video.

That is a very hard question, he said, when I asked him why he had set out on this seemingly suicidal trip one of the longest ocean crossings possible, at one of the worst times of the year. He denied that he had any death wish. And it is not like going over a waterfall in a barrel. He had prepared himself well. His boat was well found. He is an excellent navigator. Yes, I think I have courage, he said when I asked him point-blank whether he felt he was brave.

Next page