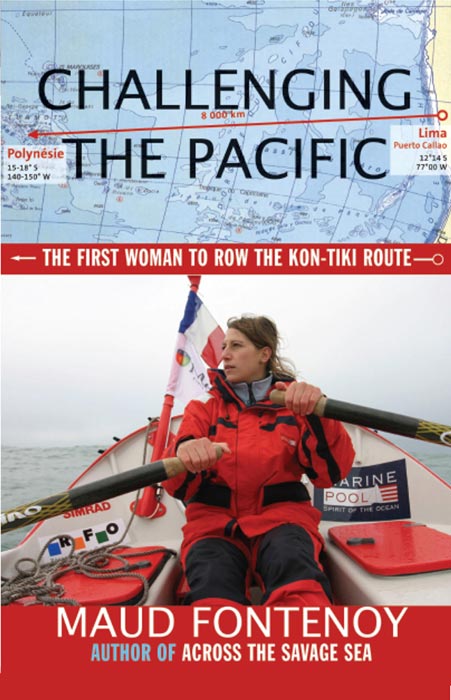

Also by Maud Fontenoy

Across the Savage Sea:

The First Woman to Row Across the North Atlantic

Copyright 2005, 2011 by Editions Robert Laffont

English-language translation copyright 2006, 2011 by Arcade Publishing, Inc.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

First published in France as Le Pacifique a mains nues by Editions Robert Laffont

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-504-5

To Chris, guardian of my dreams

You see things, and you say, Why? But I dream things that never were, and I say, Why not?

George Bernard Shaw

Contents

THE ROUTE

Departure from Lima, Peru, on January 12, 2005

Arrival at Hiva Oa, French Polynesia, on March 26, 2005

1

Emergency Dive

T HE SHARK CAME IN WITHOUT A SOUND, coldly slicing through the ocean. I fought to stay calm. Whatever you do, stay where you are. Stay quite still in your seat.

My eyes were fixed on the sleek, tapering shape just beneath the surface beside me. I was frozen with fright, my pulse racing, my insides tense and burning. All that lay between me and this dark blue menace was a film of water. With its cold eyes and steely musculature, the creature seemed invulnerable. It veered lazily around Ocor, my cockleshell rowboat, like a lone wolf looking for prey. Ocors sides shuddered with the vibration of its movement.

This one was probably cruising for sea bream, which were plentiful in the vicinity and delicious, as I could attest. It was well over six feet long, and despite my panic I quietly thanked my stars Id stuck to my strict resolution never to go swimming off the boat. Terrified and breathless, feeling very small indeed in the presence of this sleek predator, I could only sit and pray it would lose interest and go hunting elsewhere.

And suddenly it was gone, for no apparent reason. Maybe it thought I was too large a morsel.

This surprise visit occurred several days ago, around noon. I had just stopped rowing and was finishing off a ration of freeze-dried spaghetti Bolognese, dreaming of the beautiful fresh salads I hadnt seen for weeks. The sharks sudden appearance had made me drop the small aluminum-foil package containing my meal and for some time after the thought of that great sinister shape made the hair rise on the back of my head. This was my first close shark encounter of the voyage. Nor was it the last, by any means.

Little did I know that within days Id be agonizing about whether to break my resolution.

Should I or shouldnt I go over the side?

Under my feet, sixteen thousand feet of void stood between me and the ocean floor. I was more than twenty-five hundred miles from my port of departure, Lima, Peru. Alone in a vast expanse of sea, I had long since lost any physical sense of where I was. I was marooned in the presence of the elements. I couldnt afford the smallest error of judgment: there wasnt a soul to help if I ran into trouble.

The memory of all the blue-skinned sharks I had sometimes glimpsed swimming stubbornly around my boat filled me with dread. My brain churned with conflicting thoughts. I mustnt make a wrong move. Weak in the knees, I told myself stories to bolster my courage and relieve my sense of being so utterly alone.

Should I or shouldnt I?

The question kept resonating, like a bell tinkling to the rhythm of my body. My oar strokes had grown more and more leaden, ineffectual, painful. Seaweed had crept into the cockpit, which hadnt drained properly since the hawse pipes got choked by shellfish a while back. Recently, a stealthy growth of sea organisms had made its appearance beneath my sliding seat, making the tiny living space as slippery as soap. A few days earlier, the rudder had finally jammed, befouled by shellfish, and now it wouldnt shift to port. Worst of all, Ocors hull, completely covered by hundreds of barnacles, was virtually dead in the water.

For several more days I hesitated. Torn between the fear of diving beneath the surface and the ever more pressing need to do something, I nevertheless battled on with the oars. The situation grew more critical by the hour. I knew if I waited much longer the boat would come to a complete standstill. I had to make a decision.

The sea was in an untidy, ruffled mood and we were riding a slow swell from the southward. But Ocor wasnt herself. Instead of scudding over the waves, she was plunging heavily, like a wounded animal. The sky began to darken, and before long the ocean began to boil like a giant witchs cauldron. My tiny craft was also my lifeboat I had nothing else. I gripped the oars like a couple of panhandles to avoid pitching sideways.

So, the idea of going overboard in this

I shut my eyes, trying to picture myself lying beside a huge pool, swimming peacefully, letting the fresh water run softly along my flanks, relishing the bliss of relaxation. My family would be near me. Anya, my two-year-old niece, would run over to me, wanting to be caught up in my arms

Ocor heeled dully to port, jolting me back to reality. It wouldnt be easy going over the side. I was bound to have trouble hauling myself back into the cockpit. The boats hull was heavily rounded, which made her roll crazily at the best of times. I might even capsize her with the weight of my body.

But the moment came when I couldnt procrastinate any longer. I had no option. I had to careen Ocor, or stay here forever.

I had run into this same situation before, when I rowed across the North Atlantic. It had been early October, and the water temperature was no more than 57 degrees Fahrenheit. I was paralyzed by fear and cold Ill never forget the anguish of finding myself physically incapable of climbing back on board. Id spent more than forty-five minutes in the water and couldnt summon the strength to hoist myself back up.

That ugly episode had taught me a valuable lesson, and now, minutes away from an equally perilous venture, I felt helpless, vulnerable, and more terrified than ever. Because this time my body, my mind, and every other part of me knew exactly what to expect.

I had the morbid sensation that I was dipping too deeply into my reserve of luck. I felt under scrutiny, as if some imaginary being somewhere up above was waiting patiently for me to jump. I got a certain consolation in reminding myself that I always reflected carefully before making any move and I had done so in this case. Maybe that would be a point in my favor.