Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

We hope you enjoyed reading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Ethnologist and adventurer THOR HEYERDAHL became known to the world when he organized and led the famous Kon-Tiki (1947) and Ra (196970) transoceanic scientific expeditions. Both were intended to prove the possibility of ancient transoceanic contacts among distant civilizations and cultures.

In the 1947 voyage of the primitive raft Kon-Tiki , Heyerdahl and a small crew sailed from the Pacific coast of South America to Polynesia, demonstrating the possibility that the Polynesians may have originated in South America. The story of the voyage was related in KON-TIKI and in a documentary motion picture of the same name.

Heyerdahls accounts of his other incredible expeditions include Aku-Aku: The Secret of Easter Island (1958); Fatu-Hiva: Back to Nature (1974); and Early Man and the Ocean: A Search for the Beginnings of Navigation and Seaborne Civilizations (1979).

SIMON & SCHUSTER, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 1950, 1984 by Thor Heyerdahl Readers Supplement copyright 1963, 1973 by Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Published by arrangement with Rand McNally & Company

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Rand McNally & Company, P.O. Box 7600, Chicago, IL 60680

ISBN 13: 0-671-72652-2

ISBN 10: 0-671-72652-8

ISBN: 978-1-4516-8592-3 (eBook)

First Simon & Schuster printing November 1973

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Front cover illustration Mark Harrison

CONTENTS

Foreword to the 35th Anniversary Edition

S OME PEOPLE BELIEVE IN FATE, OTHERS DON T . I DO , and I dont. It may seem at times as if invisible fingers move us about like puppets on strings. But for sure, we are not born to be dragged along. We can grab the strings ourselves and adjust our course at every crossroad, or take off at any little trail into the unknown.

The pages that follow recount the story of a young man pulled up against the wall until he grasped the strings of destiny. When today I read this story which once I wrote myself, I recall the most decisive moment in my life, when I, a sworn landlubber with a fear of water deeper than to my neck, cut all ties to the land and steered out into the largest and deepest body of water on earth, into a strange adventure and an unknown future. From then till the present day, my life has been filled with adventures linked together like pearls on a thread. Pearls rarely turn up in oysters served to you on a plate; you have to dive for them. Adventure for adventures sake has never appealed to me. But I do not shun adventure if it comes my way.

I grew up as an overprotected boy. A dreamer. My university years were split between studies of man and beast. I was formally educated as a zoologist at Oslo University, but my heart was with my studies of Pacific peoples at the Kroepe-lien Polynesian Library in the same city, the worlds largest private library on Polynesia (it has since been incorporated in the Kon-Tiki Museum Library, Oslo). And as a bookworm unable to swim, I went in 1937 to Polynesia to live for a year on the jungle island Fatu Hiva, severed from contact with the outside world.

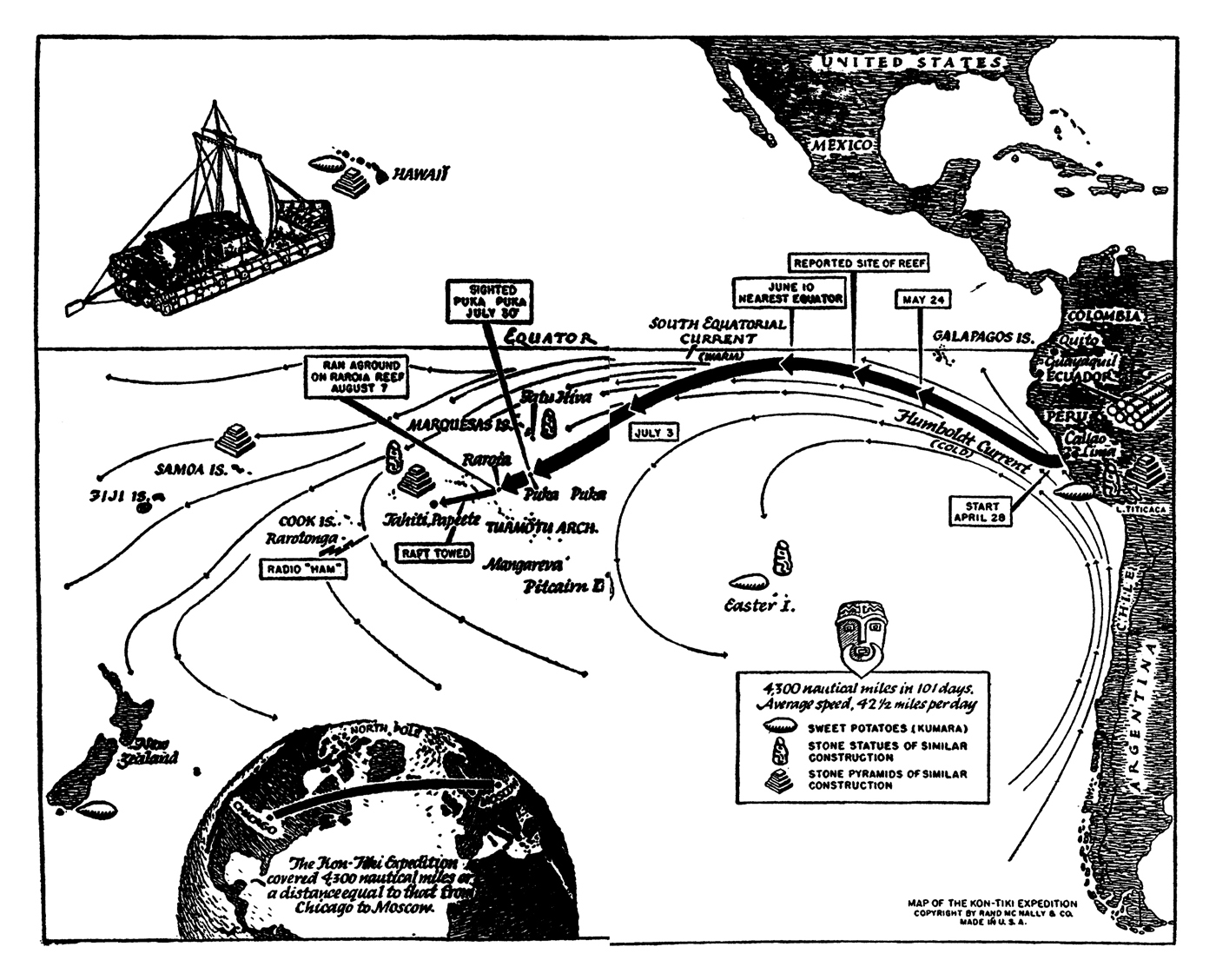

I went to Polynesia to study how animals had reached oceanic islands, carried by winds and currents. I came home with a controversial theory of how man had reached these islands in prehistoric times. Scholars had invariably assumed that all early voyagers into the Pacific had sailed and paddled straight from Southeast Asia. I disagreed. Prevailing winds and currents would prevent their traveling directly eastward from Asia. Yet there were two feasible sea routes to Polynesia: One was a circuitous route from Southeast Asia by way of Northwest America to Hawaii, and the other from South America directly to eastern Polynesia.

This book tells the story of how six young men proved that a prehistoric voyage from South America was possible, contrary to the predictions of scientists and sailors. The South American balsa raft, which scholars had claimed would sink if it were not regularly dried out ashore, stayed buoyant as a cork. And Polynesia, held to be inaccessible for a watercraft from ancient America, proved to be well within the range of aboriginal voyagers from Peru.

How did science react to being proved wrong? Among the first to yield was the worlds leading authority on prehistoric watercraft in Peru, Dr. S. K. Lothrop of Harvard University, the very scholar whose judgment about balsa rafts we had disproven. But the worldwide publicity given the Kon-Tiki voyage was considered a slap in the face by other scientists who had quoted Lothrop and based their own work and teachings on the assumption that balsa rafts would sink. From all over the world, scholars hit back, accusing us of a stunt without scientific merit. Public interest increased with the polemics. The book on the Kon-Tiki expedition became a best-seller, eventually translated into 65 languages, and our film of the voyage was awarded an Oscar as best documentary feature for 1951.

Years of controversy followed, during which scholars everywhere initially refused to even listen to the arguments behind the Kon-Tiki theory. The first formal challenge came from the Royal Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography, which asked me in 1950 to defend my views and as a result awarded me my first scientific medal. Other awards followed, in Scotland, then France. In 1952, five years after the raft voyage, I was able to publish for the first time my 800-page volume American Indians in the Pacific: The Theory Behind the Kon-Tiki Expedition . The same year, I accepted an invitation to deliver three lectures at the 30th International Americanist Congress at Cambridge University; when the congress next assembled, in Brazil, I attended as an honorary vice-president.

Nonetheless, the polemics continued. The Galapagos Islands were said to disprove the Kon-Tiki theory. They lie closer to South America than any of the Polynesian islands. If South American voyagers dared to sail all the way to Polynesia, why had they not settled the Galapagos as well? A new challenge. New library studies.

Numerous scholars had been to the Galapagos since Darwins visit in 1835. Zoologists, botanists, geologistsbut not a single archaeologist. None had come to look for early human traces that far from the mainland. The visitors all quoted one another to the effect that no human eye had seen these islands before the Europeans arrived in 1535. Having discovered that Inca balsa rafts were entirely capable of reaching the Galapagos, I brought the first two archaeologists to investigate the islands in 1953. We searched in the few level places where early rafts could have landed between the rugged lava cliffs and rocks. Four prehistoric campsites were located on three of these arid islands. From the barren soil, the trowels of the scientists scraped up large quantities of potsherds and other artifacts, many of them identified as pre-Inca by the U.S. National Museum. This proved that numerous voyagers from Peru and Ecuador had visited the island group in pre-Columbian times. Permanent settlement had been prevented by only seasonal access to drinking water.

Next page