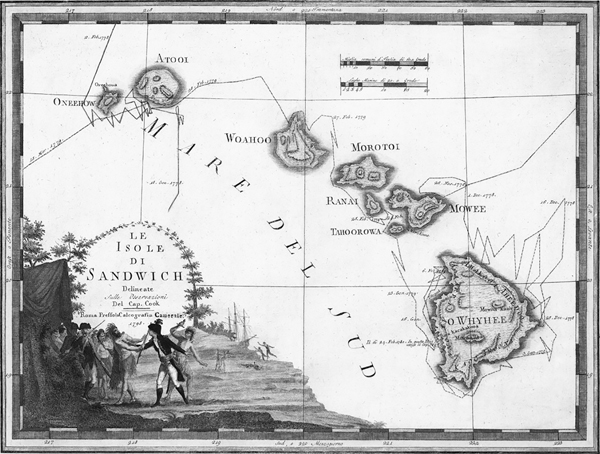

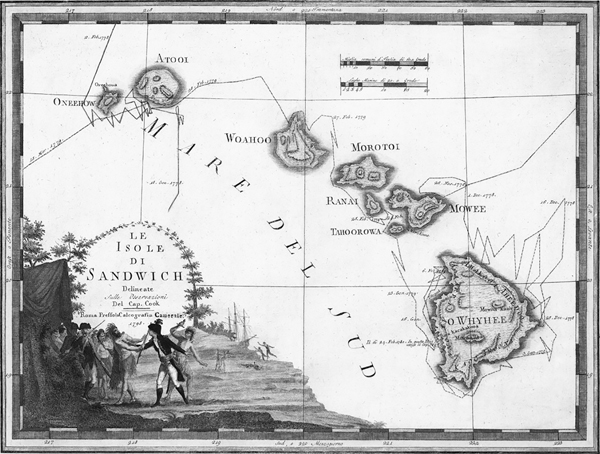

Map of the Sandwich Islands by Giovanni Cassini (Rome, 1798), based on Cooks chart of Hawaii.

STORY OF HAWAII MUSEUM, KAHULUI, MAUI.

KEALAKEKUA BAY LIES on the west, or leeward, side of the Big Island of Hawaii, in the rain shadow cast by the great volcano Mauna Loa. It is a smallish bay about a mile wide, open to the southwest, with a bit of flat land at either end and a great wall of cliffs along the middle, where in ancient times the bodies of Hawaiian chiefs were hidden in secret caves. The name of the bay, Kealakekua, means in Hawaiian the Path of the God, and in the final centuries of Polynesian isolation, before the arrival of Europeans, it was a seat of power and the ancestral home of no less a personage than the first Hawaiian monarch, Kamehameha I.

To get to Kealakekua Bay, you take the main road south from Kailua, leaving behind the more heavily settled areas of the Kona Coast and passing through a series of small towns. The highway on this part of the island runs along the shoulder of the mountain, and the drive down to sea level is a steep one. Turning off at the Napoopoo Road, you wind down through an arid landscape of mesquite and lead trees interspersed with ornamental plantings of hibiscus and plumeria. Taking a right at the bottom and following the road to its end, you come at last to a little cul-de-sac under a pair of spreading jacarandas. The beach, with its jumble of boulders, is a stones throw away, the high red rampart of the Pali looms on the right, and, squinting into the distance, you can just make out the low, scrubby outline of the farther shore.

Immediately adjacent rises the wall of the Hikiau Heiau, a large rectangular platform neatly built of close-fitting lava stones. The first time we visited this spot, my husband, Seven, and I were at the end of a long trip across the Pacific with our three sons. We had seen these sorts of structures before, coming upon them half-hidden in the forests of Nuku Hiva and high on a headland on Oahus North Shore, and once on a beach like this on the island of Raiatea. In many parts of Polynesia they are known as marae, and in the days before Europeans reached the Pacific they were places of great mystery and supernatural power. Presided over by chiefs and priests and dedicated to particular gods, they were sites of sacrificeincluding, occasionally, of humansand propitiation to ensure safe voyaging or good health or plentiful food or success in war. They were decorated with scaffoldings and carved wooden images, and often with skulls, and were governed by the incontestable law of kapu (known elsewhere as tapu and the source of our word taboo), the system of rules and prohibitions linking everyday existence to the world of the numinous, which permeated every aspect of ancient Polynesian life.

We picked our way around the outside of the heiau, trying to get a sense of what was there. What remained of the original structure was a raised dry-stone platform more than a hundred feet long and about half as wide, rising to a height of ten feet at the beach end. It was said to have been nearly twice this size when it was first seen by Europeans, in the late 1700s, and would have been an imposing edifice with a commanding view of the bay. Or so we imagined. The stone stairway up to the top of the platform was roped off, and no fewer than three separate signs reminded us that no trespassing was allowed. Visitors were admonished not to wrap or to remove any of the stones or to climb on the walls or in any other way to disrespect the site. Heiau on the islands of Hawaii have more signage than similar structures on other islands, and, given the number of visitors, its easy to see why. But encounters with the past are different when they are mediated in this way, and I was glad that our first experience of such places had been deep in a forest in the Marquesas, where we had wandered freely among the ruins, ruminating after our own fashion upon the passage of time.

Directly in front of the heiau was an obelisk built of the same black lava rock but cemented in a very un-Polynesian way. It was about ten or twelve feet high and was mounted with a bronze commemorative plaque that read:

In this heiau, January 28, 1779,

Captain James Cook R. N.

read the English burial service

over William Whatman, seaman,

the first recorded Christian service

in the Hawaiian Islands.

Here was a completely different story from the one the heiau had to tell. On the surface, it was the story of poor Whatman, dead of a stroke, whose last wish had been to be buried on shore, and of the almost accidental arrival of Christianity, the rippling effect of which would be felt in these islands for centuries to come. But the much larger story, only obliquely indicated here, was of the coming of Europeans to the Pacificthe most consequential thing to have happened in these islands since the arrival of the Polynesians themselves. And so, while we might have come simply to see the heiau, with its tantalizing glimpse of a remote and cryptic Polynesian past, it was, in fact, the intersection of these two histories that had brought us to Kealakekua Bay.

COOKS ARRIVAL IN the Hawaiian Islands marks a turning point in the history of European understanding of the Pacific. It was January 1778, and he was a year and a half into his third voyage. In the course of the first two, Cook had explored much of the South Pacific, laying down the east coast of Australia, circumnavigating New Zealand, charting many of the major island groups, even making the first crossing below the Antarctic Circle. On his third and final voyage, he was headed into new territory: that part of the Pacific that lies north of the equator. He had set his sights on one of the great chimerical objects of European geography, the Northwest Passage, and when he chanced upon the island of Kauai, he was bound for Nootka Sound.