Photograph Tane Sinclair-Taylor.

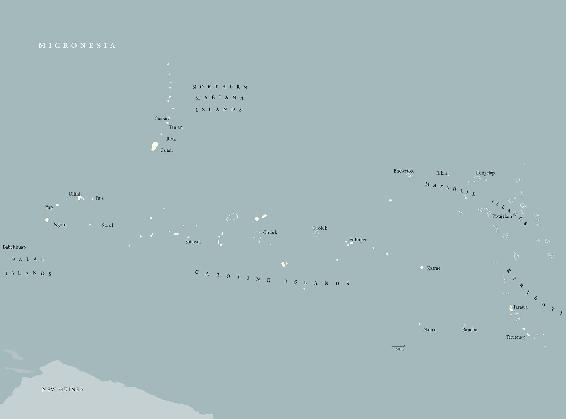

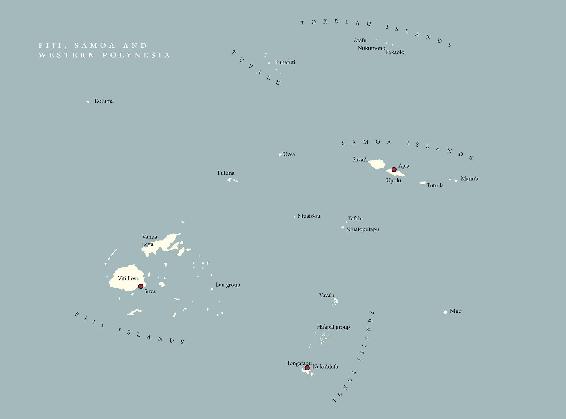

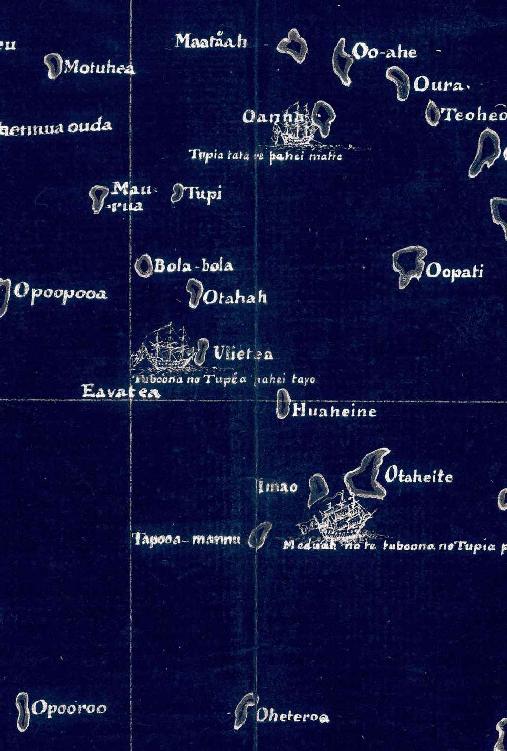

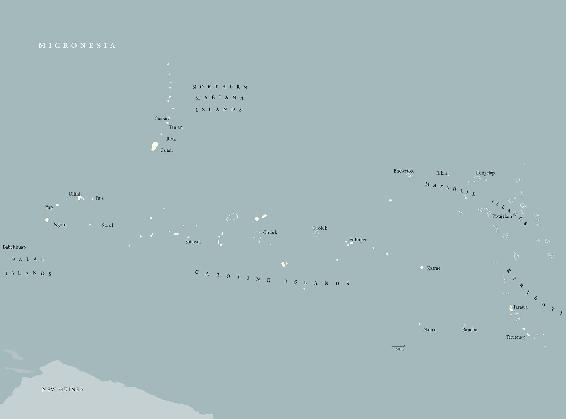

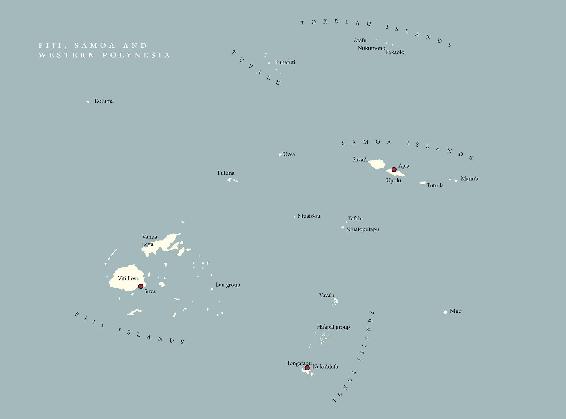

Maps of Oceania prepared by Mat Hunkin, Victoria University, Wellington; courtesy of Peter Brunt.

Maps of Oceania prepared by Mat Hunkin, Victoria University, Wellington; courtesy of Peter Brunt.

Maps of Oceania prepared by Mat Hunkin, Victoria University, Wellington; courtesy of Peter Brunt.

Maps of Oceania prepared by Mat Hunkin, Victoria University, Wellington; courtesy of Peter Brunt.

Maps of Oceania prepared by Mat Hunkin, Victoria University, Wellington; courtesy of Peter Brunt.

Maps of Oceania prepared by Mat Hunkin, Victoria University, Wellington; courtesy of Peter Brunt.

On a May morning in 2016, we left Tumon before light. We drove inland, and then along the coast to Hagta. Guam is developed, with wide roads, a lot of cars and some high-rise buildings. It feels like what it in fact is: a territory of the United States, with major military bases and too many hotels. Yet it is still irreducibly a Pacific place. As we approached Paseo de Susana, the location of the cultural village established for the Festival of Pacific Arts, it was still dark, but the air was soft, humid, faintly scented with frangipani. We passed hibiscus on the roadsides, and the breeze began to pick up. My ears were attuned to a kind of gentle rattle, a natural percussion of half-dried leaves, from the heights of the coconut palms. It was a sound Id first heard thirty years earlier in Tahiti, and had associated with the Pacific ever since.

We parked and walked towards the point. It was just getting light, and the foreshore was crowded, it seemed with thousands of Islanders, many locals, but others whose tattoos, head-dresses, skirts or shirts with flags or national colours identified them as Solomon Islanders, Fijians, Samoans, Tahitians We picked our way across coral rock. The sea was gentle, just slightly choppy as the wind rose with the sun. Perhaps a kilometre offshore, several triangular forms caught the dawn. They oscillated, approaching, and within a few minutes outrigger canoes came into view and entered the sheltered harbour as crowds began to shout, chant, and sing. The crews were standing, waving paddles, relieved after some days making passage across the open ocean from islands up to 900 kilometres (559 miles) to the southeast Lamotrek, Poluwat and Houk.

The Festival of Pacific Arts had been mounted periodically since the 1970s. In 1992, the sixth gathering had taken place at Rarotonga in the Cook Islands, and its theme had been Seafaring Heritage. For the first time, ocean-going customary canoes had made inter-island voyages, their arrival marking the festival launch. I had witnessed Cook Islands canoes arriving in Samoa in 1996. By 2016, the tradition was well established, but the event was nevertheless momentous. Navigator Larry Raigetal, from Lamotrek, in the central Caroline Islands, Micronesia, said:

These islands werent just settled by mistake. These are islands that belong to great navigators in the past, including Guam and the whole entire Pacific. We are voyagers.

His commentary resonated with the arguments of one of the most visionary and radical Pacific intellectuals of recent decades, Epeli Hauofa, a Tongan anthropologist, academic and writer, founder of the Oceania Centre, a cultural institute at the University of the South Pacific. In the early 1990s Hauofa argued for a re-imagining of the region he inhabited:

Oceania denotes a sea of islands with their inhabitants. The world of our ancestors was a large sea full of places to explore, to make their homes in, to breed generations of seafarers like themselves. People raised in this environment were at home with the sea. They played in it as soon as they could walk steadily, they worked in it, they fought on it. They developed great skills for navigating their waters, and the spirit to traverse even the few large gaps that separated their island groups.

Crowds from across the Pacific welcome voyaging canoes arriving at Hagta, Guam, May 2016.

Photograph Dan Lin.

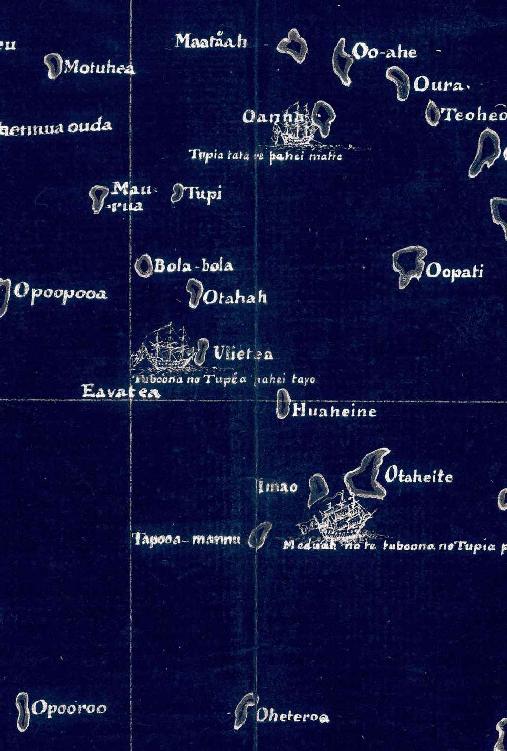

Articulated nearly thirty years ago, this was a fresh, powerful and contemporary vision; and indeed a postcolonial perspective, an optimistic one that conceived a Pacific shaped by Islanders themselves. Yet it was also a vision that some of the first Europeans to spend time in the sea of islands would have recognized. Among the earliest observers of any Pacific society to live among people, rather than just interact with them in the course of an expedition, was the Bounty mutineer James Morrison, who spent the better part of two years in Tahiti, before being captured and taken back to England. If his imprisonment at first on the voyage home and then in England was no doubt miserable, and the prospect of the death penalty terrifying, its fortunate for posterity that he was taken into custody, since he prepared an insightful early report of Polynesian life, as well as a detailed account of the experience of the voyage and the mutiny, which helped him win a pardon. With respect to Islanders customary travel by sea, he wrote that:

It may seem strange to European Navigators how these people find their Way to such a distance without the Help or knowledge of letters Figures or Instruments of any kind but their Judgement and their knowledge of the Motion of Heavenly bodys at which they are more expert and can give a better account of the Stars which rise and set in their Horizon then a European Astronomer would be willing to believe which Is nevertheless a Fact and they can with amazing sagacity fore tell by the Appearance of the Heavens with Great precision when a Change of the Weather will take place and prepare for it accordingly when they Go to Sea they steer by the Sun Moon & Stars and shape their Course with some degree of exactness.

The earliest foreign visitors to the Pacific were astounded and perplexed by the presence of people on islands thousands of kilometres from continents. As well they might have been over the millennia of human history, our species has been largely, indeed overwhelmingly, continent-based. James Cook and his naturalists and companions asked: who were these people? From where did they come? How were they able to reach islands dispersed over such vast tracts of ocean?