From Arabia to the Pacific

Drawing upon invasion biology and the latest archaeological, skeletal and environment evidence, From Arabia to the Pacific documents the migration of humans into Asia, and explains why we were so successful as a colonising species.

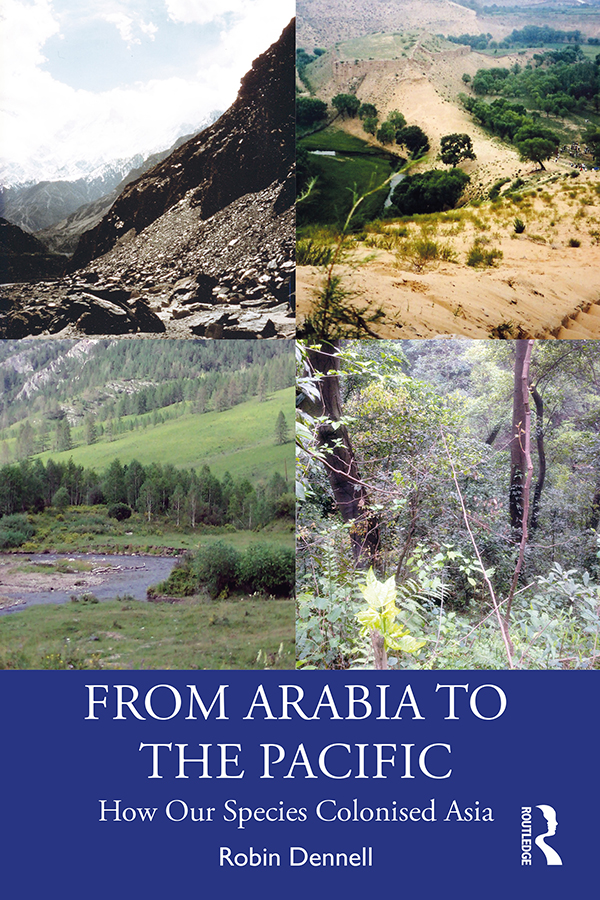

The colonisation of Asia by our species was one of the most momentous events in human evolution. Starting around or before 100,000 years ago, humans began to disperse out of Africa and into the Arabian Peninsula, and then across southern Asia through India, Southeast Asia and south China. They learnt to build boats and sail to the islands of Southeast Asia, from which they reached Australia by 50,000 years ago. Around that time, humans also dispersed from the Levant through Iran, Central Asia, southern Siberia, Mongolia, the Tibetan Plateau, north China and the Japanese islands, and they also colonised Siberia as far north as the Arctic Ocean. By 30,000 years ago, humans had colonised the whole of Asia from Arabia to the Pacific, and from the Arctic to the Indian Ocean as well as the European Peninsula. In doing so, we replaced all other types of humans such as Neandertals and ended five million years of human diversity.

Using interdisciplinary source material, From Arabia to the Pacific charts this process and draws conclusions as to the factors that made it possible. It will be invaluable to scholars of prehistory, and archaeologists and anthropologists interested in how the human species moved out of Africa and spread throughout Asia.

Robin Dennell is Emeritus Research Professor at Exeter University, UK. In his early career, he was primarily interested in the Neolithic of Europe and Southwest Asia. During 19811999, his main research was on the Palaeolithic and Pleistocene of Pakistan. In 2003, he was awarded a three-year British Academy Research Professorship to write The Palaeolithic Settlement of Asia (2009), the first overview of the Asian Early Palaeolithic and Pleistocene. Since 2005, he has conducted research with Chinese colleagues into the Pleistocene and Palaeolithic of China. He was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 2012.

First published 2020

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2020 Robin Dennell

The right of Robin Dennell to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record has been requested for this book

ISBN: 978-0-367-48239-8 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-367-48241-1 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-003-03878-8 (ebk)

For all those past, present and future interested in Asia and the history of our species

This book focuses on the first appearance of our species, Homo sapiens, in Asia. This was one of the most momentous events in human evolution, and one which resulted in our species being the only hominin in the whole of Africa, Asia and Europe. In some regions of Asia, when this happened can be indicated with some precision for example, the main Japanese islands were first colonised around 38,000 years ago. In other areas, our first appearance is known to within a few millennia: for example, from Iran through southern Siberia to Mongolia and north China, this likely happened between 50,000 and 45,000 years ago. In other regions such as India, we have very little idea of when our ancestors first appeared because of a lack of well-dated skeletal material and a shortage of well-dated archaeological assemblages. An additional complication is that the dispersal of our species across Asia was unlikely to have been a single event. Instead it is much more likely to have been composite, with at least two main dispersals across southern and continental Asia, and in Southwest Asia and perhaps further east there may well have been several episodes of dispersal, depending upon the prevailing climate and availability of water. I try to show what we think we know, and what we know we dont know about this momentous colonisation of the largest continent by our species. As I hope to show, this is a story of immense ingenuity, inventiveness and adaptation that amply demonstrates our talents as a coloniser and as an invasive species. In terms of time frames, my coverage ends around 30,000 years ago, by which time humans were present from Tasmania to the Arctic, from the Atlantic and Mediterranean to the Pacific, and were even on the Tibetan Plateau. In geographical terms, I define Asia as the area east of the Mediterranean and Ural Mountains, but I exclude the Caucasus region on the grounds that it can be better treated as part of Europe.

My main sources are the stones and bones the bread and butter of Palaeolithic archaeology evidence about the climate and environment, and of course the skeletal evidence for our species and those whom they replaced. I also use ancient DNA (aDNA) where it is available, and I expect this source to increase greatly in importance in the new few years. What I have not used is the enormous literature derived from the genetic analysis of living human populations. There are two main reasons for this decision. The first is simply one of space as there is a limit to what can be crammed into a book of this length. The second is that there has been a tendency in recent years for the traditional sources of evidence the stone tools, associated animal bones, and skeletal evidence to be downplayed in a favour of a framework established by genetic analyses of modern populations. These typically state that people with a particular genetic make-up dispersed from area A to area B at such and such a time, and attach to that narrative whichever pieces of skeletal data or archaeological evidence that are consistent with that scenario. They are often shown as maps with arrows denoting the direction of dispersal, with in most cases, a total disregard for the landscapes through which people moved. The timing of such dispersals is usually derived from estimates of rates of genetic change, and should be seen as hypotheses waiting to be tested, and not taken (as often happens) at face value. Additionally, these scenarios of when and by which routes humans dispersed take no account of the what people did in the landscapes that they colonised, how they adapted to them, what choices they made, or their climatic and environmental circumstances. In other words, they have rarely told me about the topics that interest me most. So, in defence of my own profession as primarily a Palaeolithic archaeologist, I try to show as best I can what we know about our colonisation of Asia from the evidence they left behind over 30,000 years ago rather than from the genetic make-up of people who may or may not be their direct descendants.