1 Introduction

it is well-represented in other languages of the Austroasiatic, Hmong-Mien, Tibeto-Burman, and Sinitic families, and is attested, although less well-represented, in Tai-Kadai. It is also represented in Austronesian and Papuan languages to the east. It thus appears to be a much better areal feature than Hendersons early study suggests.

The object of the present study is not limited to word-initial prenasalized stops as unitary phonemes, and so my conclusion about prenasalization as an areal feature differs from that of a recent study of phonemic prenasalization in Southeast Asia by Donohue and Whiting (2011), who found prenasalized phonemes much more robustly attested in New Guinea than in mainland Southeast Asia. As a historical linguist, I expect the phonological status of this particular feature to change, either through natural processes of fusion and simplification, or through extension by transfer in language contact situations. Accordingly, I follow Henderson in considering initial prenasalization whatever its status: morphological, phonemic, or phonetic. The nasal element in the present study may thus be (1) a syllabic nasal preceding a stop-initial root, (2) the first element of a cluster, (3) part of a complex unitary stop phoneme that contrasts with other types of stop, (4) the product of the hyper-voicing of a voiced stop, or (5) a nasal phoneme followed by a brief oral stop closure. It also appears that the primary historical source of word-initial prenasalization in Southeast Asia is the process whereby an initial light syllable is reduced, giving rise to consonant clusters. This process is reflected in the presence of both a prenasalized voiced and a prenasalized voiceless stop series in some Southeast Asian languages. The occurrence of word-initial prenasalization is therefore inextricably linked to studies of iambic (light-heavy) word prosody and prefixation as areal characteristics of Southeast Asia. Finally, word-initial prenasalization, while rare cross-linguistically, extends beyond mainland Southeast Asia to the west, north, and east, and thus is useful in re-thinking the geographical extent of the Southeast Asia linguistic area, a question addressed by other contributors to this volume as well.

Although word-initial prenasalized stops are familiar to linguists studying languages of Southeast Asia, New Guinea, Africa, and some parts of Central and South America, more significant for typological and areal studies is the fact that word-initial prenasalized stops seem to be absent from other areas: Europe, the Middle East, Northern Asia, as well as most of North America. As others have pointed out (e.g., Thomason 2000; Comrie 2007), it is difficult to use unmarked featuresthe existence of a /t/ phoneme, for exampleto delineate a linguistic area since they can be expected either to occur, or arise naturally, in any part of the world. The study of a marked feature with limited distribution is thus valuable for our common project of bringing the picture of the mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area up to date.

Of the 59 languages in Hendersons study, only 12 are characterized by prenasalized initials, and some of these she reports as having only restricted pre nasalization, e.g., limited to a single prefix (Kachin), or to a reading style (Tibetan). The best-represented groups in her study are Austroasiatic, Austronesian, and Papuan. She observes, A striking feature of this preliminary investigation has been the seeming concentration of putative areal characteristics in the New Guinea group of languages and in the tribal languages of South Vietnam. In the present state of our studies it would be premature to speak either of confluence or of dissemination in this connection but it may be helpful to think in terms of concentration areas (1965: 432). The mainland Southeast Asia/New Guinea connection has been insightfully explored with respect to prenasalization and areality by Donohue and Whiting (2011), and is addressed in terms of other shared features in the work of David Gil on the Mekong-Mamberamo linguistic area (this volume).

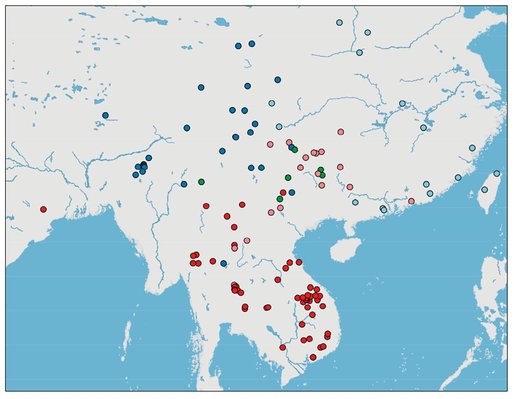

Thanks largely to three valuable sourcesChan (1987) for Sinitic, Namkung (1996) for Tibeto-Burman, and the Sidwell and Cooper SEAlang Mon-Khmer Dictionary (Sidwell and Cooper n.d.)as well as my own knowledge of Hmong-Mien languages, the map that results from the present study adds substantially to Hendersons more limited set and shows the importance of southern China as the central locus for the feature on the mainland (see de Sousa, this volume, on southern China as part of Southeast Asia).

In the sections to follow, I will first give a brief overview of the distribution of word-initial prenasalized stops by family in Southeast Asia. I will then discuss both the synchronic status of these onsets and their historical sources, and will consider the importance of this information to the establishment of initial prenasalized stops as a linguistic feature of Southeast Asia. Finally, I will discuss the relationship between prenasalized stops and some other well-known features of Southeast Asian languages.

Legend: Pink: Hmong-Mien, Red: Austroasiatic, Light blue: Sinitic, Dark blue: Tibeto-Burman, Green: Tai-Kadai

2 Geographical distribution by family

Initial prenasalized stops are found widely in modern-day Austroasiatic languages, the family whose speakers have occupied mainland Southeast Asian for the longest time. They are best attested in languages of the central groups Bahnaric, Katuic, Khmuic, and

Only a few Tai-Kadai languages spoken in southern China have initial prenasalized stops. Sui (Kam-Tai) has sub-phonemic prenasalization: in reference to /b/ and /d/, he writes It is a special feature of their articulation to carry a slight, simultaneous prenasal sound. The largest and best-known languages in this familyThai, Lao, and Zhuangdo not have initial prenasalized stops, however, which may give the impression that Tai-Kadai languages do not have this feature so well-attested in other families of Southeast Asia. It may be of significance that both Thurgood (1988) and Matisoff (1988) have reconstructed prenasalized stops for Tai-Kadai subgroups (Proto-Kam-Sui and Proto-Hlai, respectively).

Hmong-Mien languages have had prenasalized initial stops for a long time, although in some branches of the family they have now simplified to either simple oral stops or simple nasals. Correspondences involving these complex initials make clear that Proto-Hmong-Mien had a three-way contrast of * mp-, *mph-, *mb - (taking the labial place of articulation as representative) at six places of articulation,Xiong or Xong), prenasalization is retained only before ancient voiceless stops; ancient prenasalized voiced stops are now simple nasals. In East Hmongic, the prenasalized voiceless stops have lost the nasal and are now simple voiceless stops, and the prenasalized voiced stops have lost the oral stop and are now simple nasals. In modern-day Mienic languages, all ancient prenasalized stops are now simple voiced stops.

In addition to initial prenasalization as a retention of a distinctive stop series in the protolanguage, there is another recent source for initial prenasalized stops in at least one Hmongic language. Ho Ne [h nte], also called She, spoken in Guangdong Province to the north of Hong Kong, has post-stopped nasals much like those reported for neighbouring Sinitic languages (see below). The autonym for these people frequently appears in the literature as Ho Nte, which raises the predictable oral stop portion of the nasal to phonemic status. We know that this is a recent development in Ho Ne because the name means mountain people, [nte] deriving from Proto-Hmongic * nn A person/people. None of the cognates of this word across the family contains an oral stop (Mao and Meng 1986; Ratliff 1998).