To G. S. Parsonson,

doyen historian of the Pacific islands

Vowels

In the writing of all Pacific island languages, each vowel is pronounced separately, and each has only one sound, unlike in English, where a single vowel, either by itself or in combination, has a variety of possible sounds. There are, however, diphthongs that most English-speakers find difficult to reproduce exactly. These are the approximate equivalents as well as they can be expressed by orthodox English spellings:

| a = ah (half) | ai = long i (eye) |

| e = eh (ebb) | ae = long i (eye) |

| i = ee (feet) | ei = long a (fate) |

| o = aw (awl) | oe = oy (soil) |

| u = oo (full) | ou = long o (gold) |

| au = ow (how) |

Consonants

All consonants are as in English, although g is always hard. Fijian and Samoan have some spelling peculiarities: in Samoan g is always pronounced as ng; and in Fijian the following substitutions apply:

| b = mb | q = ngg (finger) |

| d = nd | c = th (that) |

| g = ng (singer) |

The glottal stop (as in alii) is an unvoiced consonant made by a momentary stopping of the breath in the throat.

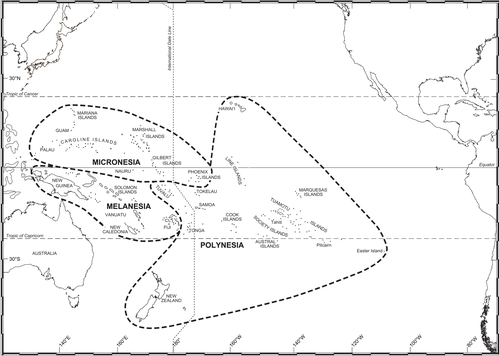

T HE PACIFIC ISLANDS were first colonised by people moving out of Southeast and East Asia and eventually occupying every habitable island and archipelago except the Galapagos in the far east of the Pacific Ocean. Considering that the ocean is a vast expanse of water covering one-third of the earths surface, and that archipelagos are separated from each other by hundreds of kilometres, this feat was the most extraordinary accomplishment of colonisation performed by the human race in its entire history. A famous New Zealand anthropologist, Sir Peter Buck, called the farthest-flung of these people the Vikings of the Sunrise. The term is flattering to the Vikings, who never performed maritime feats in any way comparable, nor were their craft as capable. Moreover, the Vikings were an iron-age people, whereas the first explorers of the Pacific did not have any knowledge of metals, a lack that makes their achievements all the more remarkable.

The histories of these scattered peoples before the coming of Europeans are obscured by the lack of written evidence. It is being filled in by archaeological research, though this will never be able to tell the stories of individual endeavour, or of the intellectual aspects of the long story. For the last several hundred years, a shadowy history becomes visible for some islands through myth, legend, genealogies and other forms of oral tradition. The histories of the Pacific peoples do not become known or told in detail until the coming of Europeans, who not only brought the art and habit of literacy to enable history to be written, but also set the history of Pacific islanders into a new trajectory.

For the last two to three hundred years the history of the Pacific islands has been shaped by and known through the activities of a succession of foreigners: scientifically minded explorers, missionaries, traders and patrolling naval officers. They were followed by settlers, plantation developers and colonial officials. Since the end of the colonial empires, Pacific history continues to wear the imprint of outsiders, including politicians, investors, development advisers, educators and tourists.

The prominence of non-indigenous people in the history of the last two centuries has made some historians pause to ask whether there was no continuing historical role for the Pacific islanders, and whether it was possible to emancipate Pacific history from its historiographical parentage in the history of European expansion and imperialism. Assuming that Pacific islanders were active agents in their own history, and that Pacific history should be seen as the record of what happened in the islands without reference to European history, a generation of academics in the age of decolonisation set out to write what they called island oriented history, or history from the perspective of the islands. The work of this school provides the bulk of modern scholarship on the islands today.

The novelty in this approach was more a matter of self-declaration than substance. There was already a considerable body of scholarship on the Pacific that was not written as a branch of imperial history. Likewise there was a good deal of it, especially mission histories, that was fully alive to indigenous agency. Nor was much of it framed in the assumption of the fatal impact that excited the scorn of the new historians. However, the phrase fatal impact, taken from the title of a work of popular history by Alan Moorehead, came to be a slogan for dismissing the work of earlier historians.

Pacific history therefore came to be conceptually and artificially polarised into two camps: first, the so-called old-fashioned imperialist works that took Pacific islanders to be passive victims of history while history was made by active, masterful Europeans. The second, and newer, camp supposed itself to be progressive in outlook and rigorous in method, giving Pacific islanders due recognition of their role in history. If there was one thing more that the new school wanted, and could not entirely claim for itself, it was that Pacific islanders should be writing the history. The new historians therefore declared their own work to be provisional, serving only until Pacific islanders should emerge to do the job properly.

The present book owes a major debt to the writers of the new histories for the wealth of information that they have uncovered and the careful professionalism of their work. It seems to me, however, that what distinguishes the new historians most was their access to finance and to historical sources on a scale unknown to their predecessors. They were thus able to get more of the story and tell it in greater detail. They were not, I think, more successful at uncovering lost Pacific island voices. The difference between the old and the new schools was not moral or intellectual, but material.

Moreover, I do not accept that the so-called fatal impact theory was used in the way that it was often alleged to be, nor for that matter that it was necessarily wrong. It is a mistake to suppose that fatal impact equates with either indigenous passivity or scholarly arrogance. The impact of Europe on the Pacific islands and their peoples was indeed often fatal. The effect of introduced diseases, firearms, alcohol, land alienation and labour recruitment could hardly be anything else in a great many cases; nor does it give a truer picture to say that failing to assert Pacific islander agency is bad history. Agency in history is often a matter of power, and that in turn is a matter of numbers, material resources and confidence. The balance swung from time to time in different directions.

Today, Pacific islanders still make their own history; there are other people not native to the region who are also making Pacific islanders history. The relationship with the wider world gives Pacific islanders new opportunities, just as it did two centuries ago, and the modern relationship also has its fatal components. The effects of nuclear contamination, the proliferation of the AIDS epidemic, bad diet and consumerism, global warming and the threat of rising sea levels gives a grimmer prospect of the fatal impact, but hardly more nightmarish than the encounter with personal, community and racial extinction confronted by many Pacific islanders in the past.